Literature: A Prose-Free National Prize and Growing Activity Abroad

Cinema: Self-Identification and Propaganda

Theatre: A Cocktail of Repressions with a Small Pinch of Positivity

Music: new names and major losses

Traditional Culture: Old and New trends

Art: Pra_bel, The Time of Women, the Cynicism Fair and Contemporary Fashion

Literature: A Prose-Free National Prize and Growing Activity Abroad

In the last two summer months and during the traditionally bohemian September the Belarusian literary landscape was full of events but lacked any excitements. The exciting news is expected to arrive with the start of an award season, which will begin in October outside of Belarus. Thus, we will take advantage of this lull to compare the processes that constituted literary life in Belarus and abroad.

In Belarus. “Extremism”, “malice” and national idea: the show goes on

Even though on September 11 some journalists and bloggers, among them publicist Zmitser Dashkevich and philosopher Uladzimir Matskevich, were released from custody and then forced out of the country, as of the end of September, 33 individuals who are associated with the Belarusian literary scene remain political prisoners in Belarus. Apart from direct repressions, the government continues its farcical show with demonstrative and emblematic political purges.

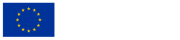

In Belarus, over the past three months, the lists of banned books have been continuously growing. These lists, which as of the end of September include 258 publications, can be found on the PEN Belarus’s useful webpage. Experts split banned books into three groups according to the status assigned them through government censorship:

- Today the official list of books that are deemed “extremist” comprises 88 books, with 13 books added within the past three months.

- The official list of “harmful books” – books, which according to the government, “can be harmful to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus” –comprises 173 publications with 63 added in the past three months.

- There is also an unofficial list, the so-called blacklist, which exists within government cultural institutions and prisons, but is not represented on the PEN Belarus website. Instead, there is a case study that examines the process of formation of this list.

Overall, the PEN Belarus resource provides an essential legal and human rights perspective on the censorship processes taking place in Belarus. Thus, the resource is especially useful for readers and authors that remain in Belarus.

Unfortunately, PEN Belarus does not keep track of the censored online sources and social media accounts that belong to cultural workers. The overall picture of repression turns out to be much more large-scale with such a statistic taken into an account. One of the examples of such “virtual repressions” taking place is the designation of an online library Kamunikat as “extremist”, where more than 60 thousand titles are gathered. Resources that get banned become only accessible through VPN, which has an adverse effect on the development of cultural awareness within the country.

The logic behind repressions can be ambiguous, but it is noticeable that the lists of “harmful content” also expand under the influence of Russian propaganda against LGBTQ+, as well as with the aim of preventing violence and the promotion of drugs. Authors who typically get designated as “extremists” are the ones whose works contain either criticism of the current Belarusian government or an overall attack on dictatorship as a form of government. The detailed analysis of the current state of repressions within the cultural scene in Belarus was done by Cichan Czarniakiewicz, the secretary of the International Union of Belarusian Writers.

Fortunately, at least for now, there are no known cases of government prosecution of either authors or readers of restricted content. Yet it is also not actually known what kind of development the formation of such lists will take. It is quite possible that the state still lacks human resources and simply postpones its “raid on museum” (metaphor coined by Alhierd Bacharevič). At the very least, one can be sure that the state struggles to grasp the whole literary landscape in the formation of a comprehensive list, as evidenced by a statement made in early September by Denis Yazerski, an official of the Ministry of Information of the Republic of Belarus, who called on citizens to identify “harmful books” and report them. Titles designated as harmful are going to be subject to confiscation and eradication.

Emblematic cleansing of the national canon is a part of, yet another episode of the government’s show which is centered on its pursuit to coin a national idea. At the end of September, state TV channel State TV(STV) named historical figures to be commemorated in reliefs on the facades of the National History Museum of the Republic of Belarus. To refer to the comprehensive analysis, which is a thorough look at the phenomenon of the formation of pantheon in post-national time and is done by an expert who uses the name F.Raubich: “The idea of forming a national pantheon in Belarus emerged with a certain, almost two-hundred-year, delay”. The expert also highlights the Soviet flair in the choice of historical figures to be canonized and parallel to historian Timokh Akudovich, their clear pro-Russian and anti-Polish bias. By comparing different drafts of pantheon sketches, the expert noticed, that writers Vasil Bykaŭ and Uladzimir Karatkievich were excluded from the final draft.

Nasha Niva suggests that “the Soviet stereotypes lie behind the selection of the historical figures included in the pantheon.” We made a similar observation in our March report on the Minsk International Book Fair. The same can be said about the Day of the Belarusian Writer, which was held on September 6-7th in Lida. The event was centered around the three themes: “the 80th anniversary of Soviet people’s victory in the Great Patriotic War; the so-called Year of Improvement (Tidying Up), declared this year; and the 500th years since the printing of the book “The Apostle” by Francysk Skaryna.” Another improvement related to literature took place in Minsk, where a wild forest park was turned into “The Garden of Verses”, which is, in a way, a visualization of the Belarusian literature school curriculum within an urban landscape, created by the young architect Uladzimir Kashkouski.

To return to the Day of Belarusian Writing, in Lida, the National Literary Prize of Belarus (formerly known as the “Cupidon” Prize) was awarded in several categories. Notably, the “Prose” category was absent from the list, which probably suggests that loyal writers in 2024 did not release any noteworthy prose works. By way of contrast, the full list of the 2024 Jerzy Giedroyc Literary Award included 19 titles. It is worth noting that competent officials at the Ministry of Information are well aware of the literary process abroad. Last year’s works by the Giedroyc award laureate and by this year’s shortlist nominee appear on the list of “extremist” books. It seems that the organizers of the state literary process are conscious of how disgraceful their situation looks. And we are not even talking about the lack of a transparent procedure for the National Prize, that we point out year after year: there is also no information on who were the jury members, or whose works were on the full and shortlists of nominees. The mere fact that not a single worthy prose book – even in Russian – was produced by any author loyal to the state undermines the prestige of the state-controlled literary scene. One is forced to diagnose the extreme dystrophy of the pro-regime literary organism.

Outside of Belarus. Discussions, events, performances: symptoms of dynamic literary life

Outside of Belarus, during the period under review, there was a certain spike in interest in literature reviews and literary analysis. It is still worth stating that its levels are not ample for a quality literary process. Even though the review aggregator Bellit.store operates efficiently, there are still not many authors writing such criticism. Yet one cannot be unhappy about the fact that, in the last few months, new discussions of literary texts appeared which are clearly worth taking a look at.

Besides criticism of the state narrative, examples of which were cited above, the clash of opinions inside the independent literary process draws attention.

One of the noteworthy examples of such recent literary criticism is the reaction towards the new book by Andrei Horvat titled “The House”, which was released in the spring of this year. The book, written in the genre of autofiction, employs a nostalgic and lyrical tone to describe the restoration of the Horvat family Palace in Narowlya, as well as to recount the history of the noble family (which shares its name with the author), making Edvard Horvat its central character. In her review of the book on Facebook, Hanna Yankuta disagrees with the novel’s adherence to a lyrical and nostalgic tone: “I have always imagined [the Horvat family Palace in Narowlya] as the place whose owners had “full control over their people”, where much blood was spilled with physical punishments occurring on a regular basis. The same can be said about the estates(domains) of almost any other noble family within the territory of Belarus.” Yankuta’s view is part of her public reflections on the history of Belarusian peasantry, which draw on historical monographs centred around the problem of serfdom within Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, written by both Belarusian and Polish authors. Such an unromanticised view on the history of Belarusian peasantry is also employed in the 2023 bestseller by Polish Author Joanna Kuciel-Frydryszak “Peasants: Our Grandmas’ History”. The book takes a sceptical view toward romanticisation of the past and of the widespread Polish fascination with the “nobility” and its Sarmatian descent, and it sheds light on the history of the Polish and Western Belarusian “common” people. In our view, this fact anticipates the Belarusian translation of Kuciel-Frydryszak’s work.

All this can be considered a left-wing turn in the study of the history of peasantry within the Central European narrative, with which Yankuta’s view can be associated. That’s why it is clear that, against the backdrop of such a “leftist” perspective, the mainstream Belarusian authors’ fascination (as in Horvat’s The House) with the nobility quite justly turns out to be an outdated trend.

Yankuta’s view is referenced by Nasha Niva reporter Mikola Buhay in his nation-centric and slightly politicized review of Horvat’s book titled “Unamusing Evenings in Narowlya”, where he highlights that the Horvat family received its privileges by serving the Russian Empire and keeping distance from the uprisings. Thus, Bugay draws a parallel between the nobility and contemporary Belarusian oligarchs.

All this does not mean that Horvat’s “The House” was met solely with hostility by critics. One of the examples of a positive response to the book is the August episode of Sergei Dubovets’ podcast.

Another noteworthy lively discussion is centered around the text by the Belarusian émigré author Kolia Sulima, which appeared on Facebook on September 25. In his text, Kolia shares his impressions of his brief visit to Minsk, made probably earlier this summer. The publication of the notes sparked a discussion around the “Minsk-Mensk” narrative, which, as noted by one of the users who remains in Belarus, had not taken place within the Belarusian literary scene since the publication of the Walancin Akudowicz’s book “I Do Not Exist” in the 1990s, which included the essay “The City That Does Not Exist”. The text by another émigré author, Tania Zamirovskaia, is a response to Sulima’s account. In it, she highlights the palimpsestic nature of the Belarusian capital (“Minsk which rewrites itself”) and points out that criticizing Minsk “from the outside” was a spiteful habit of the 2000s. It seems that a distinct core of discussion exists on social media, in which Minsk appears as a focal point, no matter where its current or former residents are located. Minsk, which cannot be denied its title of the main Belarusian city, evokes a complex and multifaceted set of feelings, making it a sensitive and often painful topic for discussion both for the diaspora and for those living in Belarus.

One of the major events within the field of literary analysis was Alhierd Bacharevič’s essay titled “People, fairytales and utopias”, which was written in German and appeared at the end of August in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung newspaper. Unfortunately, the Belarusian-language translation, which was announced to appear sometime in September is still awaited. In his essay, Bacharevič highlights his unsympathetic view toward the popularity of fantasy fiction and calls the genre “the mummy of a fairy tale”.

“Fantasy fiction relies on a rigid hierarchy. It is always about a return to some kind of “golden age,” about the restoration of the status quo (the old order), about reclaiming lost possessions. The return, the reconstruction, and the past are of the utmost importance to the fantasy genre. Its characters’ objective is to restore the old order. Fantasy is always monarchical, monochromatic, and centered – almost manically – on accomplishing this objective. Aristocracy in fantasy novels has a monopoly on decision-making, and characters, regardless of any difficulties they face along the way, must prevent modernization.”

Thus, we have looked at three instances of literary discussions initiated by Belarusian authors living abroad. One is centered around Minsk, another around the tendency toward the romanticization of nobility, and the third takes its place on the global literary stage with its criticism of fantasy fiction. One can only hope that discussions on important contemporary issues will continue.

Belarusian literature continues to play an integral role both at Belarusian cultural festivals abroad – such as “Lietucień” in Krakow and the “Tutaka Festival” near Bialystok in July – and at international literary fairs and events. One of the prominent literary events, the “Month of Author Readings,” took place this summer in the Czech Republic and Slovakia and featured readings and presentations by Uladzimir Nyaklyayew, Vital Ryzhkou, and Hanna Jankuta. Writers Alhierd Bacharevič and Julija Cimafiejeva have been participating in events in Germany and other European countries, where their books are also published in German.

Millennial poets continue to test new formats of engaging with audiences. One example is Mikita Naydzenau’s recent “reissue” of his poetry collection “Independence Square” (Płošča Niezaležnasci) in the form of video poetry on Instagram. At the end of September, Vital Ryzhkou also announced the reissue of his only poetry collection, The Doors, Locked with Keys, but in the format of a stand-up show. On September 25, a music-and-poetry event titled “Litaranoty” (Letters and Notes) was held in Poznań, featuring Nasta Kudasava with her book “My Inexpressible” (Маё невымаўля) as its headliner.

It is clear that Belarusian literature aims to be seen and heard abroad, breaking the so-called fourth wall by testing new formats of audience engagement. Belarus continues to be part of global processes, and this is due in no small part to the efforts of Belarusian writers.

Trends within Belarus vs abroads

It has to be acknowledged that the active independent literary process has been almost entirely pushed out of Belarus and exists, within the country, in the form of silence. The right to express themselves belongs only to those artists and cultural workers who are loyal to the current regime and promote friendship with Russia. To illustrate the state of things, we will refer to the opinion expressed by Siarhiej Dubaviec in his review of an anthology of Lithuanian poetry translated into Belarusian:

“…when, during the celebration of Belarusian writing, Belarusian poetry is increasingly being replaced by Russian, it is quite soothing to see that Belarusians abroad maintain the natural flow directed toward the development and enrichment of Belarusian culture, without lies, deceit or foul play. It is very sad that, in order to enter the global literary process, one has to leave Belarus, which has been forcibly blended into a kind of cultural province that doesn’t even meet the low standards of provincial propaganda newspapers.”

It is quite natural that by existing within the global literary context, the Belarusian literary process abroad acquires its shape. Publishing and book distribution, despite still facing some difficulties, are finding their footing across Europe. The number of publishing houses is growing, even if some of them currently have only one or two titles under the belt. Many literary organizations are helping to shape the literary scene by establishing prizes and festivals and ensuring Belarusian representation at European book fairs. Authors promote their books both through the publishers and independently, often via individual tours. Books are getting published both in Belarusian and in the languages of the countries where Belarusian writers now live.

Although there are still some independent publishers operating in Belarus, book publishing remains constantly under various threats: censorship and self-censorship, restrictions on the sales of works by “undesirable” authors, and limitations on holding presentations of new titles. State institutions are also subject to such control, with the looming threat of layoffs or even arrests. The outlook of the literary process, which fails to reflect the overall condition, is marked by tastelessness and servility, reminiscent in both dynamics and pathos of the Brezhnev-era stagnation. At the same time, old ideas are poured into new containers, framed with up-to-date walls and neatly tiled. Thus, it is evident that the year of tidying up is underway.

Nevertheless, interesting books in the Belarusian language continue to be published. That’s why, once again, we want to mention and recommend the media platform Reformation (Reform), which provides monthly overviews of new Belarusian titles and does not distinguish between authors who left the country and those who decided to stay. Out of curiosity, we decided to take a look at the lists for July, August, and September to determine where — in Belarus or abroad — more new releases appeared.

Here is what we found. In July, 9 new titles were released in Belarus, and 8 books were published abroad. In August, there were 8 new books inside the country and 8 abroad. In September, 10 new books appeared within Belarus and only 5 abroad. Overall, for the period under review, the score is 27:21 in favor of publishers based in Belarus. It is worth noting that last year we assessed the share of new books as 2 to 1 in favor of publishers within the country. As we can see, the gap is rapidly narrowing. It will be quite interesting to see what this year’s final score turns out to be, but for that, we will have to wait until Christmas.

Cinema: Self-Identification and Propaganda

Belarusian artists search for their identity abroad. State cinema in Belarus sacrifices its national outlook in favor of propaganda. A film shot in Belarus achieves recognition at Locarno.

Abroad

Belarusian filmmakers, who are now dispersed across different continents and countries, continue to organize in groups that currently function separately and strive to make their way by establishing connections with local film industries and by adapting themselves to new working conditions. Thus, the somewhat slow but still persistent integration of Belarusian filmmakers into the global film industry continues. Belarusian filmmakers serve as festival jury members, participate in writing competitions, and their works appear in major film festivals’ lineups.

After having its premiere in Berlin in February, Yuri Semashko’s film The Swan Song of Fedor Ozerov was invited to be part of the Nowe Horyzonty festival’s lineup in Wroclaw. The film was screened online from June 17 to August 3 as part of the festival’s virtual program. Just like in Berlin, it received positive responses from both audiences and the press. Earlier in June, The Swan Song won two awards at the Spanish FilmMadrid festival: the Young Jury Award and the Audience Award.

Through the Echoing Voices Program, Semashko’s film was also included in the lineups of the Helsinki International Film Festival and Cine-Argo in Tehran.

Although The Swan Song has a Lithuanian producer and, within festival circuits, the film represents Lithuania, both press and audiences in their responses recognize the film as Belarusian. The story of The Swan Song unfolds in an abstract and unnamed European city.

Judgement of the Dead, a short horror film by Andrei Kashperski starring Zoya Belakhvostik, was screened in Mexico City as part of the Macabro Horror Film Festival.

Mara Tamkovich’s film Under the Grey Sky was screened in New York during the Week of Polish Cinema, organized by the Polish Film Institute. The screening of the film at the Brooklyn Academy of Music was followed by a Q&A with the director herself. Tamkovich also served as a jury member at the festival of Polish narrative films, the Gdynia Film Festival. It was there, in Gdynia, that her Under the Grey Sky won the Best Directorial Debut award last year.

Director Aliaksei Paluyan and film critic Irena Kacialovich both served as jury members of the Odessa International Film Festival, which was held in Kyiv from the end of September until the beginning of October. Paluyan was a jury member of the national competition, while Kacialovich judged the European section of the festival.

The documentary feature The Last Words had its premiere on July 11 on Belsat. The film focuses on the life of Ales Pushkin, an artist and political prisoner who was tortured and died in prison on July 11, 2023. The film was directed by Roman Schel, a German filmmaker and journalist, who documented Ales Pushkin’s life for two years in the artist’s village of Bobr, Minsk, and Kyiv. The film premiered on the second anniversary of Pushkin’s death, commemorating the artist’s life.

The screenplay Heritage by Aliaksei Paluyan, who now lives in Germany, co-authored with Esther Bernstorff and Behrooz Karamizade, has been nominated for the Hesse Award for Best Screenplay. Heritage tells the story of the Belarusian family caught in the avalanche of the events of 2020.

Most Belarusian filmmakers are now stepping away from the painful topics that concern the events of 2020 and their aftermath. Andrei Kashperski, creator of the series Processes and of the YouTube project ChinChinChannel, alongside a team of Belarusian artists, is working on a pilot episode of the show which “is not going to be political.” The show is called Swingers and is co-authored by Mikhail Zui, who also co-wrote Judgement of the Dead with Kashperski. Swingers is a comedy series which will focus on the intimate lives of people in their forties. The pilot episode stars Valiantsina Gartsuyeva, Volha Kalakoltsava, Maksim Shyshko, Katsaryna Zhaludok, Aliaksandr Tserakhau, alongside American actor Douglas Emara. The creators hope the show will draw the attention of major streaming platforms like Netflix.

A team of Belarusian artists made a historical documentary animated mini-series Fairy Tales of the Old Palessia. The series focuses on nobles (Szlachta) from Homel, who, after the revolution of 1917, immigrated to Poland. Fairy Tales consists of four episodes, each eight minutes long. Documents and eyewitness accounts found in the Polish archives were employed in the making of the series. The team behind the project plans to continue their work within the animation field. Fairy Tales of the Old Palessia is expected to premiere soon on YouTube.

Filmmaker and critic Nikita Lavretski directed a new stand-up special by Idrak Mirzalizade. Idrak is a well-known comic of Talysh descent, who for a long period lived in Belarus and even studied at the Department of Journalism in Belarusian State University. The cinematography for the special was done by documentary director Maksim Shved. The show was recorded in Warsaw.

From mid-July until September, film screenings as part of the Silent Fever project took place in the courtyard of the Free Belarus Museum in Warsaw. Screenings of four silent-era films from Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, and Germany were accompanied by live music performances. One of the featured films was The Whore, produced by Belgosfilm (Belarusian State Films) in 1926. To this day, The Whore is considered the first Belarusian film. Among the musicians who performed live were Olga Podgajska and the Five-Storey Ensemble. The project was sponsored by Knyaz Maciej Radziwill.

The Belarusian Filmmakers’ Network has launched its own series of recorded live conversations (live podcasts) titled BNF:Live. The podcast’s guests are professional filmmakers, and the topics discussed include crowdfunding, production laboratories, festival selections, financing, inclusion in film, and the future of Belarusian cinema. The host of the show is director and producer Yauhen Lytkin. During the streams, he will have discussions with a number of contemporary independent filmmakers like Andrei Palupanau, Darya Zhuk, Uladzimir Kazlou, Dzmitry Frig, Leanid Kalitsenya, and Andrei Kashperski.

On August 27, online theatre VODBLISK, which screens independent Belarusian cinema (free of charge for Belarusians), announced that it goes on a vacation for an indefinite period. The decision is dictated by the current financial difficulties and also by the theatre’s plan to move to another video platform.

The first Belarusian AI film festival, Synthetic Dreams, took place from September 25 to 30. The idea for the festival came from FILMSCHOOLBY film school and Andrei Palupanau. This year’s festival was focused on Belarusian folklore, legends, and myths. The films were created by FILMSCHOOLBY graduates of the “Machine Learning for Video Creation” course.

A startup with Belarusian roots, Filmustage, had their own video on display on the famous advertising screen at Times Square in New York. The company is primarily focused on providing software that helps to polish screenplays with the help of AI. Filmustage also supplies its software to many Hollywood companies, which makes Filmustage an important part of the current American film industry. In their blog, the team writes about the Belarusian ancestry of the Hollywood film studios’ founders and constantly shares references to Belarus found in films such as John Wick and Spielberg’s Terminal.

Today, Belarus in Western entertainment productions is typically referenced as an exotic country. One reason for this image may be that, even though Belarus is somewhat of a “grey zone,” unfamiliar to Western viewers, the country’s name increasingly appears in the news. Today, the image of Belarus in Western cinema is no longer associated with Russia or other post-Soviet countries. Until recently, however, Hollywood productions tended to represent Belarus as an extension of Russia.

A German-Austrian romance film shot on location in Belarus received an award at the prestigious Locarno Film Festival. White Snail, directed by Elsa Kremser and Levin Peter—the German-Austrian filmmaking duo—won a Special Jury Award for direction, and the Pardo for Best Performance, awarded to actors Marya Imbro and Mikhail Senkov, both from Minsk. Partially filmed in secrecy in 2023, the film tells the story of a romance between two outsiders: a model aspiring to build a career in China and a painter working in a Minsk morgue.

Belarus

National cinema in Belarus continues to be in a state of stagnation caused by constant repression and all-pervading government control. Public and private productions in the country are still unable to get into large-scale projects.

On September 12, in Minsk, a screening of privately produced films took place in the small hall of the Pioner Theatre — the first screening of such a kind in a long while. The screening of four short films was followed by discussions with young filmmakers beyond the production of the films: Anton Barysau, Mikita Kahmatau, Vital Martynyuk, and Yanina Danilevich. The screening was organized by 49.cinemaclub .

Minsk—City of Film is the new exhibition that takes place at the Museum of the Belarusian Cinema History, a branch of the National History Museum. The exhibition opened on September 13 and ran until October 10. Here, visitors were able to see film stills and location photos from films that were shot in Minsk, alongside photos depicting the current state of those locations. The exhibition also features interesting facts about film productions, actors, and directors.

On September 30, the Kinocollider initiative launched its nine-month directing course under the supervision of Andrei Kudzinenka. Kinocollider promises that the course will teach students “to be attentive, work with actors, construct screenplays, and turn any idea into film.”

At the same time, it becomes clear that the national film industry is lacking in talent after many specialists and artists left the country. Class Teacher is the new film that was lauded by state media as a “groundbreaking” feature produced by Belarusfilm. It is the film whose release was accompanied by an unprecedented promotional campaign. The film ultimately proved to be a poorly executed state propaganda miscellany. Class Teacher, which premiered on September 18, tells the story of a young teacher and currently draws mostly appointed audiences to theaters. The near-amateur direction by Kiryl Khaletsky, a recent graduate of the Belarusian Academy of Arts, combined with a confused screenplay and largely weak performances, makes Class Teacher one of the weakest features currently in the theatrical repertoires. The film also incorporates cult-like propaganda of Aleksandr Lukashenko, something previously avoided even in the least successful Belarusfilm productions.

Propaganda, alongside one-sided patriotism, is of primary importance in the government film policies, much like in other spheres. That is probably why Class Teacher became the main element of a revived national film festival in Brest, which was held from September 25 to 29. The previous edition of the festival, before it was eliminated, took place in 2010. After 2010, its functions were delegated to the national section of MIFF Listapad. Class Teacher was the opening film at this year’s festival in Brest.

This year, the films in competition in Brest were, for the most part, produced by Belarusfilm and state television channels over the past five years. The narrative section of the festival included only five features, all created by Belarusfilm in 2020 — a year that continues to generate anxiety for the government. Most of the films focused on World War II, though from perspectives which aligned with state propaganda. One film that stood out was The Black Castle, an adaptation of Uladzimir Karatkievich’s novel, produced in Russia under the banner of Belarusfilm.

Parallel to the national film festival in Brest, which featured its own section dedicated to animated films, the annual animated film festival, Animayovka, took place in Mogilev from September 24 to 26. The Grand Prix was awarded to the Russian animated film River That Runs Up the Mountains, produced by the animation studio BALL («ШАР») and directed by Aliaksandr Khramtsou. Although Animayovka typically avoids political content, this year the festival received its share of propaganda. What Swamps (Marshlands) Are Silent About, directed by Julia Pintsak, was named the best Belarusian animated film produced by the National Film Studios. The film is part of the patriotically themed anthology Belarusian Memorials. Part 2. Another anthology screened at the festival was State Symbols of the Republic of Belarus: Holidays Calendar.

“Our Symbols” is yet another “Belarusfilm” production that is not a work of art but a propaganda campaign. Our Symbols is a two-part film about the flag and the coat of arms of the Republic of Belarus. The project had its premiere on September 17 in Minsk, most likely to coincide with the so-called National Unity Day.

The extensive promotion of Class Teacher marked the peak of the Ministry of Culture’s frenzied activity, with actor Ruslan Charnetskiy and the head of the Department of Cinema, Irena Dryga, as its main participants. The hysteria was triggered by Aleksandr Lukashenko’s visit to Belarusfilm on June 10. Another consequence of that visit was the unexpected merging of the two Academy of Arts departments — the Theatre Department and the Screen Arts Department. The new department, called the Film, Theatre, and Television Department, will be supervised by the “Belarusfilm” director Ivan Pavlov.

The traditionally influential role of Russia within the Belarusian film industry gains more power. Many Russian productions continue to film their projects in Belarus, and, as usual, Russian producers continue to apply for funding for joint projects from the Belarusian state budget. By signing various “collaboration (cooperation) agreements” of differing quality, Belarusian state officials, in a way, help facilitate the outflow of money and specialists to Russia.

At the same time, the feature Not Home Alone 2, produced in Russia and shot in Belarus, skipped Belarusian theatres. During its first weekend, Not Home Alone 2 became a box-office hit in Russia. The main reason the film bypassed Belarusian theatres is that it stars Belarusian actors and includes Belarusian crew members who are on the so-called “black lists.” Given the film’s popularity with Russian audiences, the third instalment of the Not Home Alone franchise is already in production—principal photography for the film took place in Minsk in July. Many Belarusian artists and specialists who ended up on the “black lists” and remain in Belarus are forced to earn a living working for the Russian film industry.

There is an ongoing, gradual process of annexation and attempts at new cultural colonization. Russian propagandist structures continue to hold events in the country. Screenings of the program RT: Time of Our Heroes took place on September 26–27 in Minsk, hosted in the National Library, which is currently overseen by the notorious Belarusophobe Vadim Hihin. Moreover, from the end of September to the beginning of October, the propagandist festival of the “Russian World” was held in Minsk and Smolensk.

In June, in the Russian city of Vyborg, during the annual festival A Window Towards Europe, took place the premiere of the “family comedy” film Draniki, directed by Belarusian-born Anna Solovieva-Karpovich. Set in a Belarusian village, the film tells the story of children who start their own business and face various challenges along the way. Produced under the supervision of Russian producers and shot in Belarus, the film is a typical example of modern imperial appropriation. Essentially, it represents Moscow’s interpretation of “Belorussia” and aligns with the films made in Russia’s Caucasus regions and other so-called “peripheries.” It seems very likely that this perspective will be attempted to be forced onto the Belarusian viewers.

Theatre: A Cocktail of Repressions with a Small Pinch of Positivity

The annual overview of events that occurred across the Belarusian theatre scene partially includes the in-between-seasons summer break. Such a gap hasn’t affected overall activity. Our report takes a look at new repressions, small moments of positivity, and recent premieres.

Elimination of the Theatre Faculty and the Move Toward the Russification of the Theatre of Belarusian Drama

The Belarusian State Academy of Arts entered the new academic year with an altered structure. The recent changes go even further than last year’s absurd government decision to merge the Acting and Directing Departments — this time, the government has decided to eliminate the entire Theatre Faculty. Considering that the Academy itself began with the creation of the Theatre Faculty, such a decision seems even more farcical than last year’s. The faculty was established in 1945 as the Theatre Institute, and eight years later, the Institute evolved into the Arts and Theatre Institute, which, during the years of independence, acquired its current name — the Academy of Arts.

Critic Anastassia Pankratava, who was the first to notice the changes in the Academy’s structure, pointed out in her report at this year’s International Congress for Belarusian Scholars that “it is very common in our country to give significance to word order, especially in the names of institutions. So, given the fact that the new department — the Department of Cinema, Theatre and Television — is also headed by filmmaker Ivan Paulau, it becomes quite clear that cinema will receive the main spotlight.”

The upcoming changes in the structure of the Theatre of Belarusian Drama, although so far only announced, already seem likely to have a detrimental impact once implemented. At a press conference held before the start of the new season, the theatre’s director, Svetlana Naumenko, stated that she plans to launch a new program titled “The Theatre of Belarusian Drama on Mondays” — featuring productions of Russian plays in the Russian language. The first production will be based on Guys’ Stories by Russian Z-writer and propagandist Zakhar Prylepin, who took part in Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and is currently under European sanctions.

The idea for Naumenko’s new Russian-language project most likely first appeared in 2010, but at the time it did not receive much enthusiasm from the administration. Now that Naumenko heads the institution, she has all the necessary means to start earning money by touring Russia with the theatre’s productions. Meanwhile, in Belarus, only four theatre troupes perform exclusively in the Belarusian language: the Theatre of Belarusian Drama, the Janka Kupala National Academic Theatre, the Yakub Kolas National Academic Drama Theatre, and the Puppet Theatre “Lyalka” in Vitebsk. If Naumenko’s new project goes ahead, the theatre — along with its tacit support for the war — will further reduce the already small number of troupes performing solely in Belarusian.

It comes as no surprise that the Theatre of Belarusian Drama now attracts small audiences. These days, it’s easy to get tickets to its performances — unlike before, when shows were often sold out. Some of our sources even claim that you can now get two tickets for the price of one, not only during the summer season, when many citizens go on vacation, but also in autumn and spring. The theatre has become just another ordinary state troupe. Once popular but now undermined by repression, the Theatre of Belarusian Drama stands on the same level as the Janka Kupala National Academic Theatre, which likewise draws little interest from audiences and faces similarly poor ticket sales.

“Grimm Sisters” gets banned. Disrespect towards the past.

The Belarusian Puppet Theatre remains the most in-demand theatre in Minsk and, quite possibly, in all of Belarus. In 2022, as audiences’ social media posts indicated, tickets were easy to get — even right before the start of the performances. But in 2023, with the absence of competition and with the theatre’s prominence in discussions on social media, things started to change, and the demand grew. In 2024, to obtain a ticket one had to be prepared to embark on a quest of sorts – long queues, such as the one in November, even caused anxiety in the neighboring Administration of the President, evoking memories of 2020. Due to such demand, the theatre decided to stop announcing the exact time tickets would go on sale.

The premiere of Sisters Grimm, which was scheduled to open the season, generated equally high interest — tickets sold out almost immediately. However, production was banned after a preliminary staging before a committee from the Ministry of Culture. The webpage dedicated to the production was even removed from the Belarusian Puppet Theatre’s website.

The reason behind this decision — as well as the logic guiding the censors’ judgment — remains unclear. “The committee that reviewed the performance considered it ‘too dark’ and too gloomy to give it the ‘green light,’” — a source told the resource Reform. The ban seems especially strange given that no one objected to another popular production, Interview with Witches, which had been drawing large audiences and had been staged by the Puppet Theatre since 2015. However, after actress Sviatlana Tsimokhina, who acted in the play, was fired, Interview with Witches was removed from the repertoire. The play has since returned, featuring a new actress and several notable changes. The updated version offers a different take on Interview with Witches but still retains the same basis.

There was some hope that the Belarusian Puppet Theatre would be spared from severe censorship and would be left alone, even under current circumstances. But the aforementioned production ban shows that there are no exceptions to the rules. Now, all that remains is to wait — will the government leave the theatre alone, or will the repressions continue?

When we were reflecting on the state of the theatre scene in Belarus in 2024, we mentioned a specific number — five. As of 2024, only five state theatres had not changed their management since 2020 (this includes theatre managers, artistic directors, and/or chief stage directors — some theatres have both positions, others only one). This year, however, head of the Gorky Theatre, Eduard Gerasimovich, passed away, and Ala Stsebakova, head of the Theatre-Studio of the Film Actor, was fired. Now, only three theatres across Belarus have management that had not been altered: the Grodno Regional Puppet Theatre, the Slonim Drama Theatre, and the Paleski Drama Theatre in Pinsk. Out of 28 troupes, only eight currently have theatre managers, and only nine have artistic directors or chief stage directors.

These facts illustrate not only the infamous “turning of the page” in action but also an ongoing “reset” — the process of assigning managerial positions to individuals loyal to the state, indifferent to the relatively free theatre scene of 2010s.

The firing of Ala Stsebakova, who was the head of the Theatre-Studio of the Film Actor, serves as a clear example of disrespect towards the history of the theatre. In the announcement of Volha Dziuldzia’s appointment as the new theatre manager — posted across the theatre’s social media pages — there was no acknowledgement of Stsebakova or of her role as the theatre manager. Her dismissal was likely not politically motivated, since she was loyal to the state, and she may have simply retired due to age.

Since the 1980s — the time when the legendary actor Boris Lutsenko worked there — the Theatre-Studio of the Film Actor has not been among the most prominent theatres in Minsk. Its role in the contemporary theatre scene is relatively small. Nevertheless, Stebakova managed the theatre for decades, at least in its financial aspects, and contributed significantly to its development. But the “page was turned,” and no mention of Stebakova can be found on the theatre’s website.

For those who might think this lack of acknowledgment is insignificant, there is an even more striking example. Dzmitry Garelik, former manager of the Homiel State Puppet Theatre and a major figure in its development, was convicted of spreading extremist materials in January 2024. He was dismissed from his position that same year and died on January 1, 2025. No information about Gorelik appears on the theatre’s website. When the newspaper Art prepared a special issue dedicated to Homiel and its region, all references to Gorelik were removed, and the issue had to be reprinted. Future scholars seeking to understand Homiel’s cultural history will find there no mention of one of its key cultural figures — Dzmitry Garelik.

Russification and war. Baroque opera. Home staged shows.

Here is our brief overview of other theatre-related events that took place specifically in Belarus.

In our previous report, we mentioned that Belarusian theatres were forced to adopt a new funding model, under which the government provides 50% of the financing, while the remaining 50% must be earned by the theatres themselves. This has caused theatres to adapt to new conditions. For example, the Theatre of Belarusian Drama staged the play “The Mourning Song” at the Central House of Officers, where the Puppet Theatre also staged its production of “Hotel Belvedere.” By staging plays at multiple venues theatres can sell more tickets and earn additional income. However, the aforementioned productions staged at the Central House of Officers, by being removed from their original smaller and older stages, have inevitably lost some of their charm and quality.

The push toward Russification continues. Kupalauski is no longer just a theatre — it has now been turned into a sort of registry office. It is now possible to get married there, with the ceremony conducted in the Russian language.

And now, let’s move to Mahilyou, where a touring troupe staged a play based on the life of the wife of Emperor Peter the Great — the very emperor who once ordered the city of Mahilyou to be set on fire. Meanwhile, in Minsk, the musical “By the Reichstag Flag” was staged. The production was sponsored by the Russian company Rosatom.

Today, the theatres’ main priority is to illustrate the events of World War II. For example, Tatiana Kushal, manager of the Minsk Regional Puppet Theatre “Batleika” located in Maladzyechna, shared that the theatre currently lacks a creative director. She offered the position to director Dzmitry Nuyanzin.

“The first thing that he did — even before formally starting in his new role — was to gift our theatre the play ‘Winners’, which is about children working the rear during the war. It tells the story of children who worked in the fields, on farms, and in factories to help bring the long-awaited victory closer. I use the word ‘gift’ because Dzmitry worked on the play in his spare time,” says Kushal.

The National Book Award has announced its winners. The collection of plays for young adults “Avatars of the Theatre,” written in Russian by Vlada Alkhouskaya, won the award for Best Dramatic Work (Best Achievement in Drama). Olkhovskaya is a writer of detective fiction and is also known for her comedy play “Trickster Club,” which is currently part of the Youth Theatre’s repertoire. At the same time, many playwrights — writing in either Belarusian or Russian — whose works are staged abroad and explore important social issues, continue to be overlooked.

There is also some positive news, of which we will mention only a few examples. One must remember that sometimes silence is the best option and it allows many projects to be realized.

The National Academic Bolshoi Opera and Ballet Theatre decided not to tour Crimea, thanks to resistance from the theatre troupe and public reaction. The same troupe also announced its first Baroque opera production, based on Handel’s “Acis and Galatea.” For the Opera Theatre, which traditionally focuses on 19th-century works, this is a step forward.

The Theatre of Belarusian Drama announced that its new season will open with a production based on Uladzimir Karatkievich’s novella “Chariot of Despair.” The same theatre continues its lecture series titled “Belarusian Directorial Approaches in the 20th Century.” These lectures help preserve cultural memory and reintroduce audiences to names that have been partially forgotten.

Home stagings of contemporary Belarusian plays also continue to take place in Minsk. This kind of home-staging approach was popular in the Soviet Union — the very type of country Belarus, in a way, seems to be turning into.

Theatre Forum in Poznań. the Stagings of Belarusian Plays

Unlike in Belarus, the state of theatre activity abroad remains stable. Immigrant troupes and individual artists can express themselves freely, though they are forced to seek both funding and audiences.

Poland still remains the epicentre of Belarusian theatre life abroad, with the forum “Druga próba. Teatr ponad granicami” being its most prominent event. “Druga próba” is a forum for Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Polish artists, held in Poznań. One of the highlights of this year’s forum was the premiere of the play “Say Hi, Abdo” (Say Hi to Abdo), directed by Valiantsina Marozava and based on a text by Mikita Illiinchyk. The play is set in the not-so-distant future — specifically in the year 2035 — when, in place of the European Union, the Euro-Islamic Union has been established.

Also staged at the forum was the play “Ten Hours from Home,” directed and written by Jenia Davidzenka, based on the accounts of three immigrant girls. The forum also included a panel discussion titled “Belarusian and Ukrainian Theatre in the Time of War and Repressions,” as well as stage readings of contemporary Belarusian plays.

Among those who continue their work are the “Kupalauсy” (formerly of the Kupala Theatre), who are about to launch their sixth season. The troupe has announced upcoming productions of the play “Extremists” in Vilnius and “The Suitcase” in Warsaw.

This year, however, there has been no news about the Belarusian theatre festival Inex Fest, which had taken place in Poland for two consecutive years. But the initiative INEXKULT, which is responsible for the festival, continues its work. INEXKULT announced new productions: the play “What Are You Looking For, Wolf?” in Gdańsk, and “Whisper” in both Gdańsk and Warsaw.

New plays continue to be staged, among them the play “Refugees of 1915,” which premiered in Białystok and was directed by Andrei Novik of the By Teatr project. The play explores the horrors experienced by the inhabitants of Eastern Poland at the onset of the First World War, who were forcibly evacuated to the farthest regions of the Russian Empire.

The play “Neurostorm,” directed by Viktor Yahorov of the Teatr Beznazvanii initiative, premiered in Warsaw. In “Neurostorm,” artificial intelligence breaks free from the chains of the algorithm and begins to behave like a human being, exhibiting emotions and free will.

Individual artists also continue to work. Ihar Shugaleeu has joined the troupe of Warsaw’s New Theatre. Aliaksei Lialiauski, who had not been heard from since his departure from the Puppet Theatre, is now staging the play “Ecce Homo,” based on Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels,” at Karlsson Haus in St. Petersburg. Most probably, Aliaksei, like many other artists, has no choice but to stay and work in Russia. Meanwhile, in Warsaw, Yura Divakov is preparing to premiere the production of his musical cabaret Dolores Imperfecti. Full Strip Soul, which tells the stories of real-life sex workers from Ukraine and Russia.

Music: new names and major losses

From July to October, Belarusian musical life was reminiscent of an emotional rollercoaster. From one angle, one could see the new heights reached by Belarusian artists on international stages; from the other — the significant losses: the artists the scene lost this year. In Belarus itself, a number of major music festivals were held, new names emerged, and a famous American musician visited Minsk.

Belarusian bands play international festivals, and Maybe Baby goes viral

Summer is the time of year when the most famous music festivals take place. This year, many Belarusian artists performed at some of these festivals. At the beginning of July, Molchat Doma played at the prominent Open’er Festival in Gdynia. In November, the band will headline Hipnosis in Mexico.

Metal bands are not inferior to the overall achievements of Belarusian musicians on international stages. The brutal death metal band Extermination Dismemberment played at Wacken, a prominent metal festival in Germany. The band highlighted its Belarusian roots by starting their performance with an intro from a famous song by Pesnyary.

In the beginning of July, the band Flower&Pines played at Inne Brzmienia, the festival which took place in Lublin. Flower&Pines play experimental music that is composed of different, peculiarly mixed genres: from dark cabaret and industrial to post-metal. In September, the band released a 20-minute live performance that was recorded inside the cathedral.

On the 9th of July, Max Korzh played a sold-out concert at the “Narodowy” Stadium in Warsaw. The “Narodowy” is a 58,580-seat stadium, and the concert itself was attended by 70,000 people. The tickets for Korzh’s show were all sold out within five days. The show caused a stir in some Polish and Belarusian media outlets, since some of Korzh’s fans were trying to make their way into the standing area, where tickets were much more expensive. The show was paused until the trespassers returned to their seats.

After the show, it was reported that the Polish government would deport 57 citizens of Ukraine and 6 citizens of Belarus for causing civil disorder during the concert. The Prime Minister of Poland, Donald Tusk, highlighted that the law violators have the chance to leave the country willingly, or they will eventually be forcibly deported.

Burning Man this year welcomed its first-ever Belarusian camp with the allusive name “Mara” (Dream). Belarusian DJ Sir Gay played his completely new set of 55 tracks performed in the Belarusian language. He titled the set Voices of a Nation in Exile: From Dictatorship to the Dancefloor.

Belarusian artist and singer Anastasia Rydleuskaya took part in an international theatre festival in Łódź. Her other works were part of this year’s Warsaw Gallery Weekend exhibition.

In the eastern part of the globe, the main event was the music video by the artist Maybe Baby from Zhabinka, Brest Region. It is a diss track aimed at the Russian artist Instasamka, in which the Belarusian artist performs part of the song in her native language. The fact that some of the lyrics in the song are performed in the Belarusian language caused many Belarusians to make their own videos with parts of Maybe Baby’s song in their mother tongue playing in the background. Today, there are over 12,500 TikTok videos that are part of this trend.

It is quite clear that Belarusian artists today gain a much stronger footing in international markets. But for now, the post-punk, metal, and phonk bands are the ones that receive most of the spotlight. Many Belarusian artists continue to work in Russia — a situation that is driven by the absence of a language barrier between the two countries, the presence of money in the field, and the existence of familiar infrastructure.

Return of LidBeer and the visit from the American star

The musical scene in Belarus was not standing still either. American singer Jason Derulo visited Minsk at the end of July. Derulo is famous for his collaborations with well-known musicians – he has worked with Lil Wayne, Maroon 5, and Snoop Dogg. One of his own music videos has reached almost 2 billion views on YouTube.

In Minsk, Derulo headlined a series of parties at one of the bars on Zybitskaya Street. He also had meetings with the Prime Minister, Aleksander Turchin, and with NOC President Viktor Lukashenko. With the latter, he discussed the possibility of an upcoming show in October, and Derulo expressed his desire to perform a concert in Belarus.

Around the same time that Derulo was in Minsk, many festivals were taking place across Belarus. The festival of Slavic mythology, The Way of Tsmok, was held on 9–10 August in the Berezinsky Biosphere Reserve.

At the end of August, Belarusian band Police in Paris and Nevika performed at the electronic music festival Poima, which took place in Vitebsk.

Belarusian bands were also represented at the revived Lidbeer festival. Among the bands that played there were Barysauski Trakt, Davay na Ty, Parade of Planets, and Police in Paris.

The well-known Belarusian band Drazdy has decided to return to performing live after a hiatus. In June, the band’s frontman, Vital Karpanau, stated that the band would no longer be giving live performances. However, something changed, and Drazdy seemingly abandoned their commitment to leave the stage, announcing new shows in regional centers across Belarus.

At the end of September, Intervision was held in Moscow. With participants from 23 countries, Intervision is an alternative to the famous European song contest, Eurovision. This year, the singer from Vietnam, Duc Phuc, took first place. Belarusian singer Nastsiya Kravchenko, with her song Matylyok (Moth), took sixth place.

The Belarusian government continues to attempt to attract more international artists to the country. However, these attempts have so far been only moderately successful. The vast majority of performers at festivals and concerts in Belarus still come from Russia. Belarusian artists living in Belarus continue to perform, but largely within their own country. They support each other, organize collaborative concerts, and even try to vacation together.

Concerts Banned and New Challenges Faced by Young Artists

The frontman of the band Red Stars, Uladzimir Selivanau, was not as fortunate as the band Drazdy. In a recent post on VK, the artist shared a photograph of the diploma he received from a KGB major general for performing the song Love on the Barricades (Barricade Love) in front of an audience consisting primarily of officers. In the same post, Selivanov added that some “grey strangers” from the Ministry of Culture had decided to ban his upcoming concert. As Selivanau writes, someone was offended by the word “syphilis,” used in the lyrics of the very same song for which he received his diploma.

Street musicians in Hrodna were also affected by government restrictions. They are no longer allowed to perform in the neighborhoods of the city center. The news about the restrictions was reported by three Hrodna residents. On social media, citizens expressed their anger, stating that the government’s decision to deprive street musicians of the right to perform in the city center takes away one of the city’s hallmarks.

The band Dzieciuki from Hrodna was branded “extremist.” Now, any communication with the band’s members carries the risk of criminal liability for Belarusians.

Belarusian siloviki (government police) detained two executives of event agencies — Ilya Petrakovski of Blackout Studio and Aleksandr Manishev of Atom Entertainment — as well as the head of the Palace of the Republic, Maksim Prikhadovski, and executives of the ticket service kvitki.by. The cause of their detention was a chat created by the event organizers Org By, the agency that had been branded “extremist.”

Still, there was some positive news. At the end of August and beginning of September, three Belarusian bands from Minsk toured across Europe.

The KLIK team organized a contest for young artists called The Call, which was won by the artist Domsun.

The Belarusian music scene also suffered some significant losses. On 6 September, news broke of the passing of Aleh Tumashou. Aleh was a former singer of the band Ulis, a member from 1991 to 1994, and the lead singer on the band’s album Dances on the Roof.

Four bands (with the exception of Petlia Pristrastiya [Noose of Passion]) announced their dissolution. In August, Petlia Pristrastiya announced a large-scale European tour spanning 23 venues. There is apprehension that this tour might be Petlya’s last. In September, the band’s singer, Ilya Charapko-Samakhvalau, announced that he would be leaving the band.

Starting this summer, the band Soz decided to temporarily pause live performances, citing the negative social environment as the main reason. The decision was announced by Ales Plotka, the band’s frontman.

Bands Son of Deni and Naka also ended their careers. Anastasia Shpakouskaya, Naka’s frontwoman, reported the decision to close the band’s chapter in Belarusian music history.

Recent Media Projects and New Releases

There are also quite a few recent music media projects. For example, Gorizont Live records Belarusian artists performing live inside the Haryzont factory. K6Live is a new music show, whose first episode was recorded with the band LOS. Journalist Aliaxandr Charnukha announced his new musical show, Sepultura Alive, which will premiere on October 16. Alexander stated that every month the channel will broadcast new live performances by Belarusian musicians.

Even though government restrictions create serious challenges for Belarusian artists, they continue to endure and perform, finding new ways within the conditions at hand. At the same time, support comes from emerging media projects that shine a spotlight on the Belarusian music scene. It is clear that not all musicians can overcome the pressures of the current environment, the many challenges, and creative blocks. This is likely the main reason some bands put their projects—or even their careers—on hold. Unfortunately, this is a recurring pattern in history.

Belarusian Rap, Techno, and Folk-Inspired Releases

From July to October, Belarusian artists released over 400 new tracks.

The band Syndrom Samazvanca channels the tradition of Belarusian folk song in their new record, Mahajba. In Mahajba, Belarusian folk merges with psychedelic, craft rock, rockabilly, and blues genres. This experimental approach allows two distinct musical planes to coexist—the artist’s personal vision alongside the country’s folk tradition. One of the record’s key features is its long, immersive jams.

Syndrom Samazvanca is not the only band drawing on Belarusian tradition. The band Relikt released their new single Bursoniki, inspired by and named after the 1990s Belarusian comic book Where Do Bursoniki Live?

The band Shuma released the EP Bagna, where hypnotic vocals guide the listener into the realm of national Belarusian rave.

The duo Police in Paris, one member of which is the grandson of Uladzimir Mulyavin, released a techno version of the famous Belarusian song Jas Was Moving Down the Clover. The track quickly became part of the Belarusian cultural landscape; the clothing brand Mark Formelle even invited the band to participate in one of its advertising campaigns.

The alternative rock band Zvonku from Minsk released a new album, The Swing, and also shot a film based on the album.

After four years of silence, composer Dzivia returned to the scene with an epic collaboration with Dutch folk artist Gealdyr, whose music is featured in the TV show Vikings: Valhalla. One of their singles, Try Iskry, is based on a Belarusian myth about the creation of the world, in which Perun struck three sparks from a stone during a battle with Viales.

“Saudade” is the new record released by the rapper Murovei, composed of three songs in the Belarusian language. In Saudade, Murovei takes nostalgic Portuguese aesthetics and weaves them into Belarusian reality. Artists Nemiga and Maybe Baby also released new songs partially in Belarusian.

One of the breakthroughs of the last month is 21-year-old rapper Pazniaks from Hrodna. A short video for his latest single, Hawaiian Pizza, reached 1 million views on Instagram. This comes alongside generally positive critical assessments of Pazniax’s work.

On streaming services, Belarusian artists reach millions of listeners. On Spotify, Andromeda surpasses Molchat Doma by more than two million listeners: 5,387,166 compared to Molchat Doma’s 3,002,642. On Yandex Music, Max Korzh, Iowa, and Bianka are among the most popular Belarusian artists, with Korzh approaching six million listeners, and Iowa and Bianka with slightly over five million listeners. Belarusian artists enjoy greater recognition on Yandex Music than on Spotify: 42 artists have over a million listeners on Yandex, compared to only nine on Spotify.

Belarusian music continues to evolve within an unstable environment. On one hand, small liberal “beams of light” appear, such as the visit of American singer Jason Derulo. On the other hand, many Belarusian artists must navigate constant restrictions and bans, very small-scale tours, and “extremist” brandings.

For artists living and working in Belarus, performing in the West becomes increasingly difficult—especially after the recent closure of the last border crossings with Poland. More and more artists seek entry into the Russian market, where there are venues to perform, no language barrier, established audiences, and financial opportunities.

There is no denying a certain revival in the country’s festival scene. Yet, today’s festivals remain far from the level seen in the second half of the 2010s. Most festivals are headlined by Russian artists loyal to the regime and are usually sponsored by online casinos. Western artists rarely appear. One positive aspect is that the festivals have not become events composed solely of Russian artists—Belarusian bands continue to perform at almost every festival and even headline Lidbeer.

The Belarusian music scene remains under the influence of broader political agendas. With no signs of restrictions being eased, Russian artists have come to dominate the scene, attracting larger audiences on streaming platforms, headlining festivals, and performing concerts in Minsk.

It would be an understatement to say that the government does not support Belarusian artists—the authorities actively create obstacles for musicians. These obstacles typically take the form of touring restrictions and various types of censorship, which make it extremely difficult to develop an independent music industry.

Traditional Culture: Old and New trends

In our previous report, instead of organizing its content into thematic categories of festivals, dances, songs and crafts, we highlighted certain trends observed both in Belarus and abroad. From July to September, earlier trends largely continued, and, within Belarus, there remains a strong emphasis on craftsmanship and on the use of traditional Belarusian culture for the purpose of tightening ties with Russia. Abroad, Belarusian groups continued taking part in local cultural initiatives, alongside an increasing number of entertainment-focused video content promoting traditional culture.

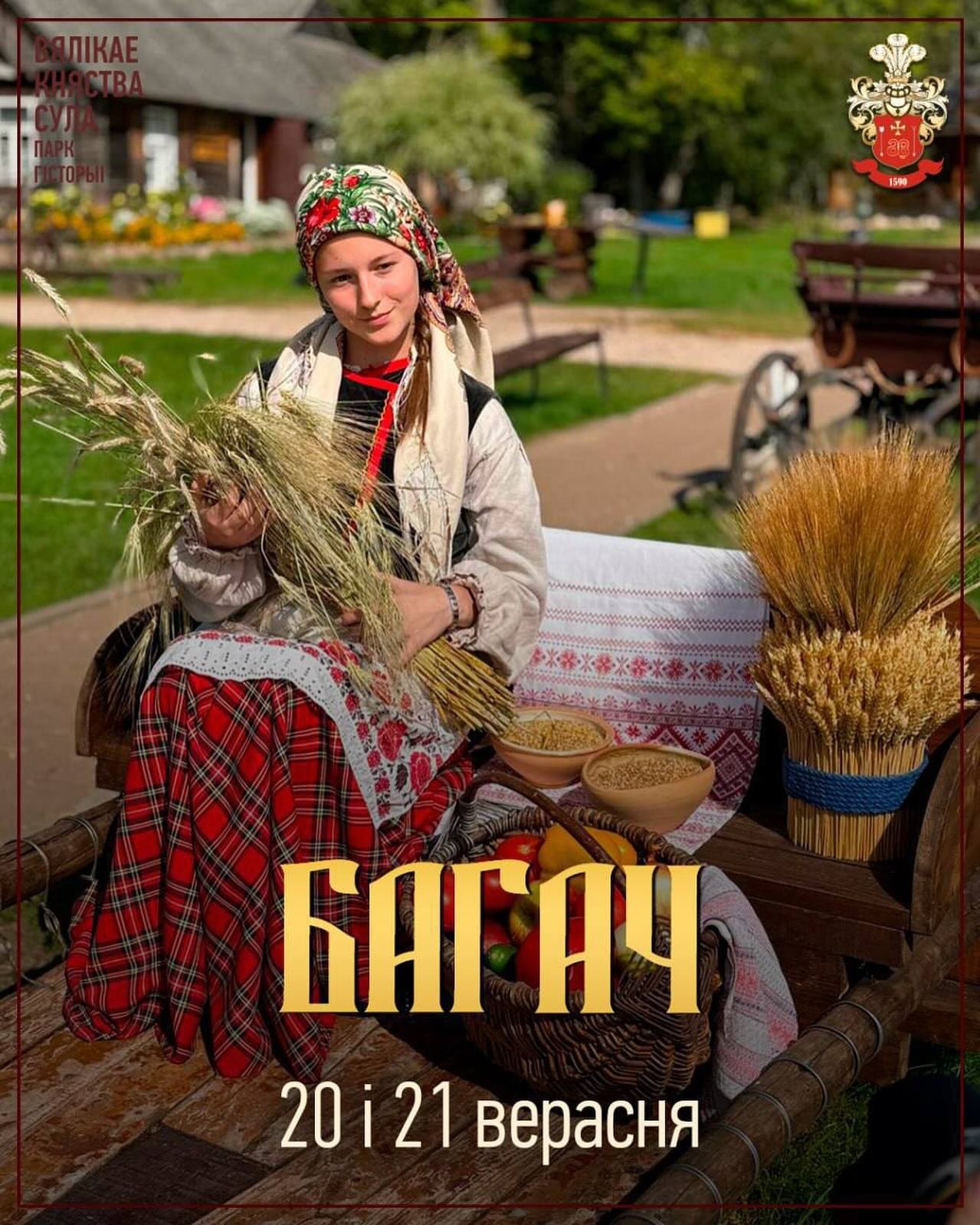

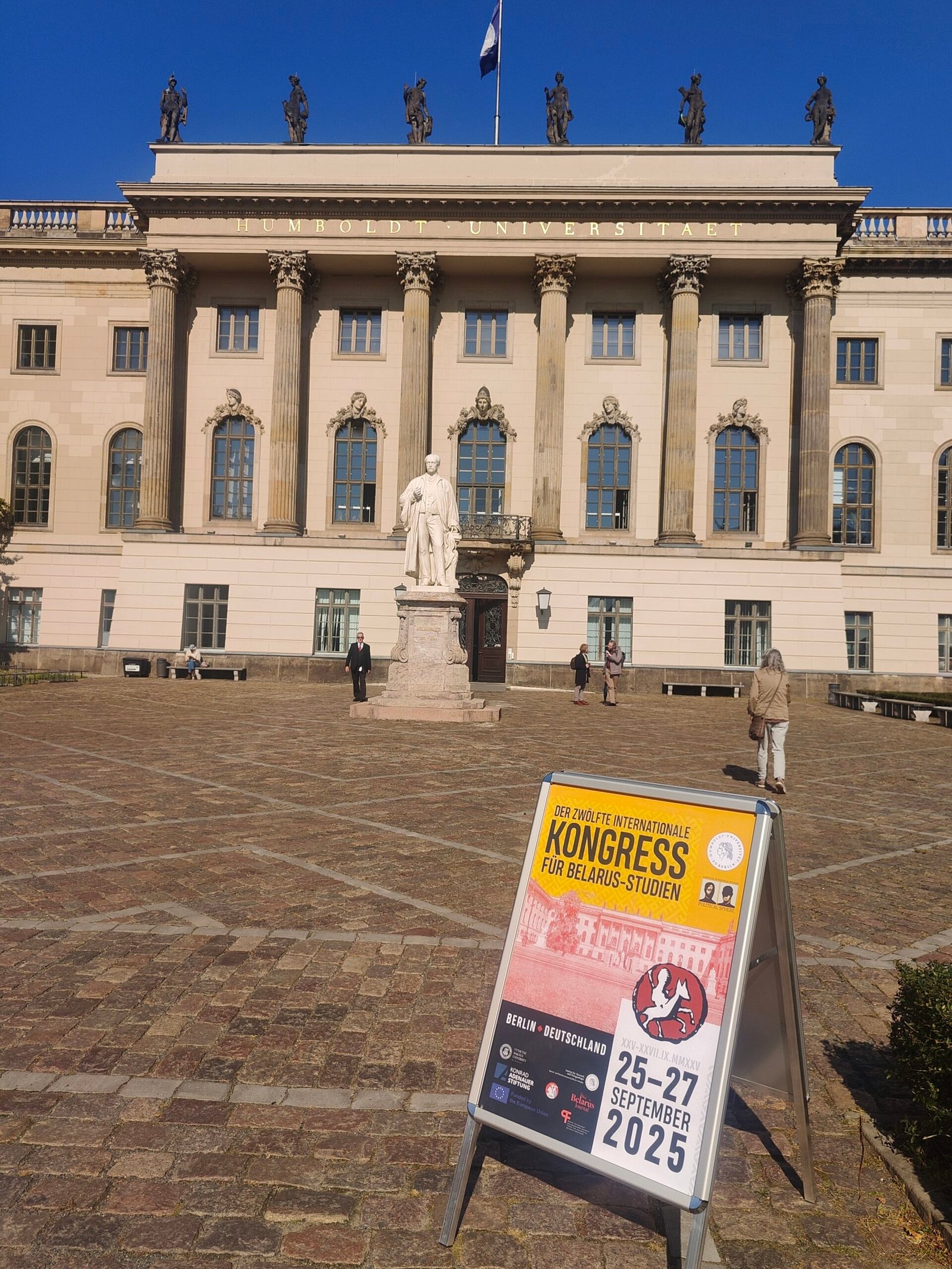

Additionally, we noticed a growth in the number of culinary festivals and a widening of the geographical scope of the Belarusian traditional harvest festival, Bagach. Additionally, we examined the role of traditional culture research within Belarusian social sciences and humanities, drawing on the program and outcomes of the 12th International Congress for Belarus Studies, held in September in Berlin.

Old Trends Continue

As usual, in Belarus, many festivals and exhibitions are focused on craftsmanship: weaving, vycinanka (papercutting), nabivanka (woodblock printing on textiles), pottery, and straw weaving. A defile (fashion show) of traditional Belarusian outfits was held on August 20 at the Museum of the History of Belarusian Literature and became one of the most talked-about events on social media.

The use of traditional Belarusian culture to highlight the close relationship with Russia continues. In our previous report, we wrote about such a program being implemented in the Mogilev region, and now it is the turn of the Vitebsk region. At the Ethnography Museum “Mlyn” in Orsha took place an exhibition of Russian traditional Khokhloma painting (wooden items). Also, in the Vitebsk Regional History Museum, the exposition “Traditions of Abramtsevo Through The Ages” was held. And, in Minsk, the Belarusian-Russian performing arts contest “National Soul” took place.

This tendency to use traditional Belarusian culture for political purposes is also characteristic of state ideological events. The Dozhynki festival, which was previously held at the national level and is now organized at regional and district levels, is almost entirely used for this purpose. Many ethnographic zones can also be found at the “Slavianski Bazaar in Vitebsk” festival and during “The Days of Belarusian Traditional Writing.”

Belarusians living abroad continue to take part in cultural initiatives in the countries where they now reside. The Belarusian duda (bagpipe) was heard at the Festival of Traditional Art in Poznań, at the Duda Players Convention in Domachowo, and at The True Musicians Tournament in Szczecin. The band “Belarusian Miracle” (Belaruski Tsud) and the dance club “Oyra” performed at the Festival of Nations (Tautų mugė) in Vilnius. In Georgia, among the initiatives dedicated to Belarusian traditional art are a singing group in Tbilisi and a dance group in Batumi. Both of these initiatives rarely take part in Georgian events, which can be explained by the language barrier and the cultural contrast between Belarusians and Georgians. However, sometimes groups participate in events organised by immigrants from Russia and Ukraine living in Georgia.

In July–August, the final episodes of “Vacations in Podlachia” were shown on the Belsat television channel. From “Vacations,” viewers can learn about the cultural traditions of the Podlachia region, located on the border between Belarus and Poland. The show “Star Thread” (Нітка зорка) returned from its break; however, no new episodes on traditional culture have been released so far.

“Bagach” Festival from Irkutsk to Belostok

This year, “Bagach” celebrations, which occur during the last two weekends of September, took place in Minsk and across its regions: at the Museum of Folk Architecture and Folkways in Azyartso, in the history park “Sula”, and at the country club “Festivalniy.” Celebrations also took place in the Brest region, at the Museum of Podlaskie Region’s Folk Culture near Wasilkow, close to Belostok, and even in Siberia – at the Taltsy Museum of Architecture & Ethnography, located in the Irkutsk region. The celebration in Taltsy was organized in cooperation with the Malaryta district of Belarus. However, it is worth noting that there is no ethnographic evidence that the “Bagach” festival had ever been celebrated in this Siberian city before.

The main symbols of the “Bagach” festival are a candle, grain, and a sheaf. It seems odd that these symbols are rarely present in photographs accompanying mass media reports on the festival. Most photographs show people standing beside traditional wooden architecture and near various treats.

The growing popularity of the Bagach festival might be explained by an attempt to replace another festival, Dazynki, which many Belarusians associate with the Soviet period and “performative” folklore. In this regard, Bagach is more closely connected to Belarusian tradition, and even harvest songs can be heard during the Bagach celebrations.

Culinary Festivals and more

Many culinary festivals were held between June and September: the karavay (bread) festival “Father’s Bread” in Svisloch; “Karavay from Paulauski” in Slonim’s Navasiolki village; “Delights from Motal” in Ivanava district; “Delights from Dvorishche” in Lida district; “Polessky Misgurnus” in Pinsk district; “Porridge – Our Wet Nurse” in Putrishki village in Grodno region; the karavay contest during the Dazynki festival in Vawkavysk; and “Dranik from Voronovo”

Dishes included in the “Living Heritage of Belarus” (the inventory of intangible cultural heritage of Belarus) were presented in Lida during the Days of Belarusian Writing. A festival dedicated to khaladnik (beetroot soup) was held in the history park “Sula.”

Most culinary festivals took place in , in western part of Belarus, in Grodno and Brest regions. While we cannot be certain that no culinary festivals occurred in the eastern part of the country, our experts were unable to find mentions of any on social media or in the press. Some western festivals were part of larger events, but Belarusian mass media still reported on them, unlike in the east. One possible reason is that dishes from western Belarus are better known and more frequently included in the inventory of intangible heritage, whereas the eastern part has fewer recognized dishes. Some eastern dishes listed in the inventory—under regional or national nominations—include kletski “with spirits” from the Vitebsk region and various grated potato dishes. These may be considered insufficiently original or distinctive to become local culinary brands.

It is possible that the khaladnik festival in Sula was inspired by the šaltibarščiai (cold beetroot soup) festival in Vilnius, held from May 30 to June 1. Belarusians living in Vilnius even organized their own mini-festival at the bar Karčma 1863. We also know that khaladnik festivals were held in Wroclaw on May 31 and in Batumi on June 7. In this way, Belarusians living abroad celebrated their traditional culinary festivals earlier than those who live in Belarus. Festivals dates are influenced by the fact that it is much more comfortable to eat outdoors in warm weather.

The popularization of craftsmanship, which we discussed earlier, often takes the form of festivals. During the summer, many festivals that are hard to classify under a specific category also take place—such as the Festival of Humor in Malyja Aŭciuki and “Sporovskie Haymaking” (Haymakers).

As we have noted, abroad, events related to traditional culture usually occur as part of broader Belarusian cultural festivals. Large-scale events solely dedicated to traditional Belarusian culture have not yet emerged.

Scientific Research

The 12th International Congress for Belarus Studies showed that topics concerning traditional culture remain not very popular today. Only 2 panels out of 52—less than 4%—were specifically dedicated to such issues:

- Dudas of Europe: Education Through Borders and Generations

- Unresolved Past: Belarusian Ethnology, Cultural Anthropology, and Folklore Studies Through Reverse Perspective

Some presentations addressing traditional culture took place as parts of the other panels, but this does not change the overall picture—traditional culture remains poorly represented within social sciences and humanities.

On the other hand, the research that does take place is highly productive. Among 23 Congress Award winners, 4 works focused on traditional culture:

- Yanina Grynevich – How the Nation Was Learning to Sing. Minsk: Belarusian Science, 2023. In the category “Humanities (monographs),” her monograph on folklorist Anton Grynevich shared 2nd and 3rd place (overall points) with Volha Romnova’s The Other History of Belarusian Cinema.

- Volha Labacheuskaja – (Introductions) Archive of Forgotten Expedition: Vaclau Lastouski’s Expedition of 1928. London: Skaryna Press; Warsaw: Czabor Publishing, 2024. Pages 10–43. Awarded 1st place in the category “Humanities (articles).”

- The same scholar, Volha Labacheuskaja, also won a grant competition for the support of scientific publications with her monograph Abrok. Abidzennik: Female Ritual Practices.

- Additionally, another grant competition supported the future publication by Alena Liashkevich, titled Symbolic Functions of the Belarusian Bagpipe (“Duda”) in Narratives of Modern Urban Bagpipes.

Thus, it can be stated that although traditional culture is studied by only a few scholars, their work is recognized and acknowledged by the scientific community.

Art: Pra_bel, The Time of Women, the Cynicism Fair and Contemporary Fashion

I am finishing writing this text on the day of the celebration of the reunification of the two Germanies in Düsseldorf, on the bank of the river Rhine, which is a transparent, yet bloody divide between civilizations, where history continues to teach and to resonate. However, the small, only two-week gap between the holidays, since the National Unity Day in Belarus is held on September 17, showcases the profoundly different paths of time and nations.

Over the past five years, an actual unity seems to be at a distance for those who continue to be prosecuted for their political views within the country, and for those who live abroad and are excluded by the government from what it calls unity, the celebration of which the state holds on September 17.

That’s why it is so peculiar to read the news about the formation of the pantheon of national heroes, which includes only one painter, Mikhail Savitsky, who was also a captive in a death camp in Düsseldorf during the Second World War, and quite possibly caught the “Arno Breker virus,” which perfectly rhymes with the Soviet canon.

Artist as an Archive

Sculptor Kanstantsin Kastsyuchenka, who once represented Belarus at the international art exhibition La Biennale di Venezia in Italy, is now working on a monument with a negative stance toward modernism; at the same time, the building he is not unfamiliar with, which was once home to the Painting and Sculpture Creative Workshops of the USSR Academy of Arts and a haven of sorts for an academic approach to art, is gradually transforming into a venue dedicated to contemporary art (the National Centre for Contemporary Arts of the Republic of Belarus), where the exhibition “Archive: Spaces In Between…” curated by Dzina Danilovich is currently taking place.

The focus on archives remains crucial for Belarus, where there is still no free access to state documents, where the history of repressions, atrocities, and exterminations is kept under lock and key, where there is a certain cult of repression, and where every generation has to form itself from scratch. The exhibition “Archive: Spaces in Between…” is about history and the past, and it is the exhibition that speaks in a modern artistic language, where what is missing (hence “spaces in between”) is more important than what is present.

Sergei Shabohin, who is a famous curator, archivist, and editor of the platform Kalektar, is simultaneously an institution and an archive embodied. His artistic praxis is a continuous work on the formation of art archives, and this year his work, which is a new part of the project he began in 2009, “Reliquary XX–XXI. Version 6: Bird Conclave,” was exhibited in Riga. “Reliquary XX–XXI. Version 6” is centred around fragments of now-deceased artists’ works, where birds play not a mere illustrational role, but serve as either messengers or harbingers of death, or symbolize transition. The gathering and organization of such archives prevent the works from being destroyed or forgotten.