We continue our series of interviews with projects supported by ArtPower Belarus with funding from the European Union.

The Northern Lights Film Festival has existed for more than 11 years and has repeatedly changed its form and format during that time. The most significant transformations took place after 2020, when the team was forced to continue its work in exile. Since then, the festival has effectively been re-invented each year: screening formats, technical solutions, financial models, and approaches to audience engagement have all been reconsidered.

Volha Chaykouskaya, founder and director of the Northern Lights Film Festival and a producer, notes that the Belarusian programme has become one of the festival’s key areas of focus. It emerged in response to the lack of platforms for independent Belarusian cinema and as an effort to maintain a connection with audiences inside the country. Part of the programme is implemented online, while another part takes place through offline screenings in various European cities, including Warsaw, Vilnius, and Tallinn.

“For the team, the Belarusian programme is not an additional feature, but an essential part of the festival’s mission — a way to support independent Belarusian cinema and create space for it to meet audiences despite all the restrictions and risks.”

Why did you decide to apply to ArtPower Belarus?

For the festival team, applying was neither symbolic nor “just in case” — it was a pragmatic step shaped by the festival’s post-2020 reality. Volha explains that the project operates in a context where traditional revenue sources for cultural initiatives largely no longer function: there are very few commercial screenings, the online format remains the primary one, and free access has become part of both the mission and a condition for accessibility for Belarusian audiences.

“Grant support is wonderful, and without it our project would simply be impossible to carry out.”

The director of Northern Lights openly acknowledges that “sustainability” for the festival does not mean ticket sales and profit, but rather the ability to sustain the project through various grant sources and careful planning over time.

In the case of ArtPower Belarus, there was another important factor: trust in the programme’s infrastructure itself. Volha explains that she had known about the programme for a long time; it had always been within her field of attention, and the team deliberately followed announcements and deadlines in order to apply on time. ArtPower Belarus was perceived as part of a broader European system of cultural and media support, where grant funding serves to sustain projects of clear public value that cannot survive on commercial income alone.

For Volha, this also reflects a fundamental difference between funding models. In the European approach, such initiatives are supported precisely because their value cannot be reduced to commercial success. For Belarusian projects, this carries additional meaning: it is about preserving cultural space under adverse conditions, where work with language, cinema, and identity often relies not on institutional backing “at home,” but on communities and international partnerships.

What was made possible thanks to the programme?

Support from ArtPower Belarus allowed the team not only to deliver another edition of the Belarusian programme, but to significantly strengthen both its content and the festival’s technical and organisational foundations.

The first and key step was the full-scale organisation of an open call and film selection process. The team received the resources to announce the open call, process and review all submissions, and curate the programme at a professional level.

This made it possible not only to screen completed works, but also to maintain a competitive framework, involve an international jury, and offer filmmakers a transparent selection process. For independent Belarusian cinema which often lacks regular screening platforms this structure is especially important.

The second major outcome was a substantial upgrade of the festival’s online infrastructure. Thanks to the grant, the team was able to switch to a new technical provider and effectively relaunch the online platform:

“We were able to move our online platform to a new technical provider, an Estonian company. There was a great deal of work done on the backend, the design, and the adaptation of the platform to the festival’s needs, including considerations of security and accessibility for audiences in different countries.”

In the Belarusian context where issues of security, copyright, and risks for filmmakers remain acute this represents a crucial step in strengthening the online format and expanding access to films.

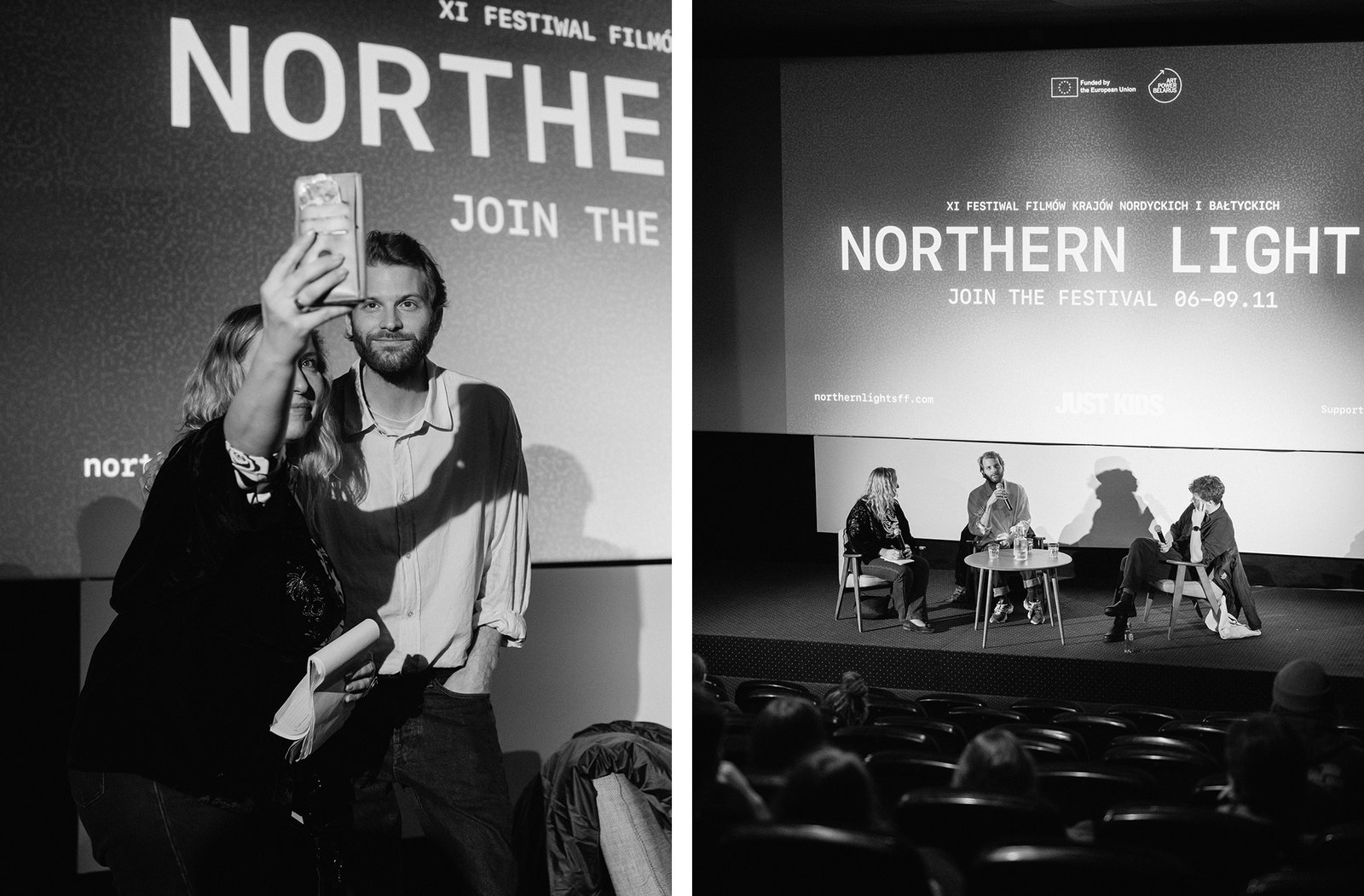

Finally, the grant made it possible to reinforce the festival’s offline component. The team organised screenings in several cities and worked directly with filmmakers, including bringing some participants to attend the screenings:

“We were able to organise offline screenings in Vilnius, Warsaw, and Tallinn, and also bring some of the filmmakers there. This was possible precisely thanks to the grant.”

What changed after participating in the programme?

Participation in ArtPower Belarus was significant for the team not only in financial terms. Equally important was the very fact of support as a signal that the project is needed, visible, and carries weight within a broader cultural context.

“The team is very happy that the project is being supported… It’s not only financial motivation, but also a form of recognition: ‘Oh, great we are needed, we are interesting, we are convincing.’”

According to Volia, this sense of recognition directly affects the team’s morale and internal resilience. The festival operates in challenging circumstances, and many team members have to combine their involvement in cultural work with other jobs in order to sustain themselves. Even if the grant does not solve all material difficulties, it allows people to remain engaged in the project and continue their work.

“Of course, it doesn’t pay for their life for a whole year… but it gives us the opportunity to keep working, including with Belarusian content and the Belarusian language.”

Challenges of participating in the programme

The process of preparing and submitting a grant application remains demanding and time-consuming, even with many years of experience behind it.

“Grant applications are always a lot of work. I can’t say I love filling them out, but it’s a useful process: it forces you to structure your thoughts and make your vision of the project more organised and clear.”

Volia emphasises that one of the main challenges is describing the project in a way that is understandable to people who are unfamiliar with the context who may know nothing about the realities of Belarusian culture or the history of the festival itself.

“A person who has never heard about the project before must immediately understand what you do and why. But when you’ve been living with it for years, everything seems obvious to you, so you have to reread and rewrite it dozens of times to be sure it’s explained accurately and clearly.”

Another key task is realistically assessing the team’s capacities both financial and organisational. This is especially important when a project includes technical changes or work with new platforms and tools, the outcomes of which cannot always be predicted with precision in advance.

Balancing ambition, responsibility, and actual resources thus becomes one of the central challenges in preparing an application. At the same time, this process helps the team better understand their own project, its limits, its strengths, and its possible directions for development.

Results of participating in ArtPower Belarus

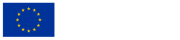

One of the strongest and most emotional outcomes for the team was the offline screenings and the community’s immediate, live response. Volia especially highlights the screening in Warsaw, which unexpectedly turned into a real event:

“In Warsaw, our screening of Yury Siamashka’s Fyodor Ozerov’s Swan Song went extremely well — it was a complete sell-out. People were even sitting on the steps, and for the team it became a very important moment: you can see that Belarusian cinema is able to fill a hall and generate a truly engaged audience response.”

For the team, this was more than just a successful screening; it was proof that there is genuine demand for Belarusian content, even despite difficult subject matter and a broader sense of audience fatigue.

Another observation that was confirmed during the festival was the sustained interest in short-film formats. Volia notes that these programmes often feel the most “alive” in direct contact with viewers:

“We’ve noticed that short-film programmes work really well with audiences. When short films are curated into a single programme, the format turns out to be in demand: viewers actively watch, discuss what they’ve seen, and ask questions.”

A separate important outcome was the work around the film Under the Grey Sky by Mara Tamkovich and its screenings in different cities. This coincided with the film’s broader international context and gave additional weight to the Belarusian screenings:

“We managed to screen Mara Tamkovich’s Under the Grey Sky in Vilnius and Tallinn, and it turned out to be very timely: during that period, the film received a nomination for the European Film Academy Award European Discovery — Prix FIPRESCI, and the screenings became an additional opportunity to make it more visible. In this way, we supported the visibility of Belarusian cinema within the European professional space.”

Less visible outcomes

Alongside the visible results: screenings, audience engagement, and numbers there were also less noticeable but strategically important shifts. One of them was the launch of an accreditation system and the first attempt to build a more structured approach to working with media and industry professionals.

“At the same time, the festival introduced the INDUSTRY START accreditation for emerging Belarusian filmmakers and film students, with access to special offline screenings and meetings in Vilnius, Warsaw, and Tallinn making it easier for them to enter the professional field and build contacts.”

Volia admits that at the beginning this initiative may look modest and requires significant resources:

“We introduced accreditation. It was the first time we had ever done something like this. Only 12 people registered, but we understand that this is a process, and we want to keep developing it.”

At the same time, the team sees long-term potential in this direction, including for increasing the international visibility of Belarusian cinema:

“We want to work not only with Belarusian journalists, but also with international ones. It’s very targeted work, because you often have to explain what Belarusian cinema is and why it matters. In essence, it’s educational work.”

Plans for the future

After implementing the Belarusian programme, the festival team is not slowing down and is already thinking about the next steps. Among the priorities are further strengthening the festival’s offline presence first and foremost in Warsaw, developing new partnerships and collaborations, and searching for formats that will allow the festival to remain relevant in a rapidly changing context.

Volia also highlights an important milestone that opens up new opportunities for the project: the festival’s acceptance into the international Human Rights Film Festivals Network.

“We were accepted into the prestigious European Human Rights Film Festivals Network. We hope that through this network we will be able to further promote Belarusian cinema.”

Another direction of reflection concerns the festival’s own history and the accumulated cultural “legacy” it has built over the years. During more than a decade of work, a whole system of visual manifestos, slogans and identities has emerged, something that could potentially become a standalone project.

“Every year we have our own slogan, manifesto and visual identity. This year we launched the festival under the slogan ‘We Are Just Children.’ Over 11 years, we’ve created enough material for an exhibition or even a book.”

What would you advise those who are only planning to apply?

Volia Chaikovskaya’s advice is clear and practical: don’t create internal barriers for yourself, keep learning, and treat the selection process as a process not as a verdict about your personal worth.

“I would also advise not to take a rejection from the expert committee personally. Keep trying and ask for feedback on how you can improve your application. But most importantly, believe in the strength of our community together we are capable of doing many meaningful and valuable things.”