The overall situation: administrative ecstasy versus “new Europe”

Comeback: Belarusian literature in search of new identity

The most important of the arts: cinema as a bureaucratic project

Belarusian theatre: “dark times”

Pop & rock. Cancellation and battles for online success

The overall situation: administrative ecstasy versus “new Europe”

The review of the situatuon with Belarusian culture at a short – quarterly – distance doesn’t let us define global tendencies and significant trends. But we can surely mark major features of a new cultural order.

Its most important marker is the continuation of forming two opposite motion vectors: westernization (gradual joining the European cultural space) and Russification (bureaucratic and enforcement agencies pressure on the creative class). It’s not just the traffic in different directions. It is the existence based on different maps of meanings.

The more time passes, the more it is obvious how naive were the hopes from the previous era to have a harmonious “union” of the official culture industry and the independent creative force. They seem to be not just different methods of work and views of culture and its levels but completely incompatible life forms. Each of them treats the opposite as imminent danger.

Recently state culture has ultimately turned into the authoritarian repressive branch of enforcement agencies. In fact the power vertical of bureaucratic and ideological pressure on figures of culture is being formed, and its main goal seems to be the elimination of “wrong” ideas and disloyal employees. The inertial uniformity becomes the main feature of the acceptable cultural product, and accountability now is the indisputable seal of quality.

Most of the events that happen in the Belarusian cultural space exist in the ritual and declarative format of a fascinating game without purpose and meaning. And it makes the question of the artistic value and national consciousness if not missing, then not significant. The official culture successfully turns into the imitation project of the colonial administration.

The consistent and persevering disposal of “risky” subjects and “inconvenient” people creates the most comfortable public environment possible, on the one hand. On the other hand, it stimulates the revival on the new level of the classical “catacomb culture” of the Soviet period: secret theatre, private film showings, home readings, online cinema festivals and Internet music releases. The game of senses and heavy metaphors together with encrypted messages. The creators and the public get out of sight of the authorities and dive into the mysterious world of conspiracy culture.

The total destruction of the cultural ecosystem of the nominal “stabilization” era determines the fate of creative projects and communities. And if we are really at the brink of “the era of silence” from concerned and confused heroes of the past (there are almost no new works from “the generals of rock”), the collapse of former opportunities and arrangements encourages the new wave of creative search. It seems inevitable that a fresh generation of creative youngsters will arise, and they will lack high-quality education, a legal opportunity to express themselves, relevant cultural experience, a developed value system and articulate self-identification. Their intuitive Belarusianity has little chance in the home country but gradually creates the critical mass of those who disagree with the existing state of affairs. Spontaneous Belarusians are back in trend – even if their low-quality rhymes look quite pathetic.

Regarding the cultural events and initiatives beyond the borders of the country, it should be said that, by and large, they create not “new Belarus” but “new Europe”. Our unique local experience and inimitable energy multiplied by actual foreign technologies and European management are forming a whole new area of opportunity – in comparison with the provincial slowness of the country with our origin. After two years of the cultural shock the time of texts and events steadily comes.

These days personal cultural self-determination (regardless of the address and registration) becomes a private adventure and experimental censorship-free exploration of a patchwork cultural area. New authors get into the non-obvious zone. Which gives the unfinished project of new Belarusian culture the distinctive smell of risk and unpredictability. Courage is our second nature.

Emptiness is a challenge and an offer.

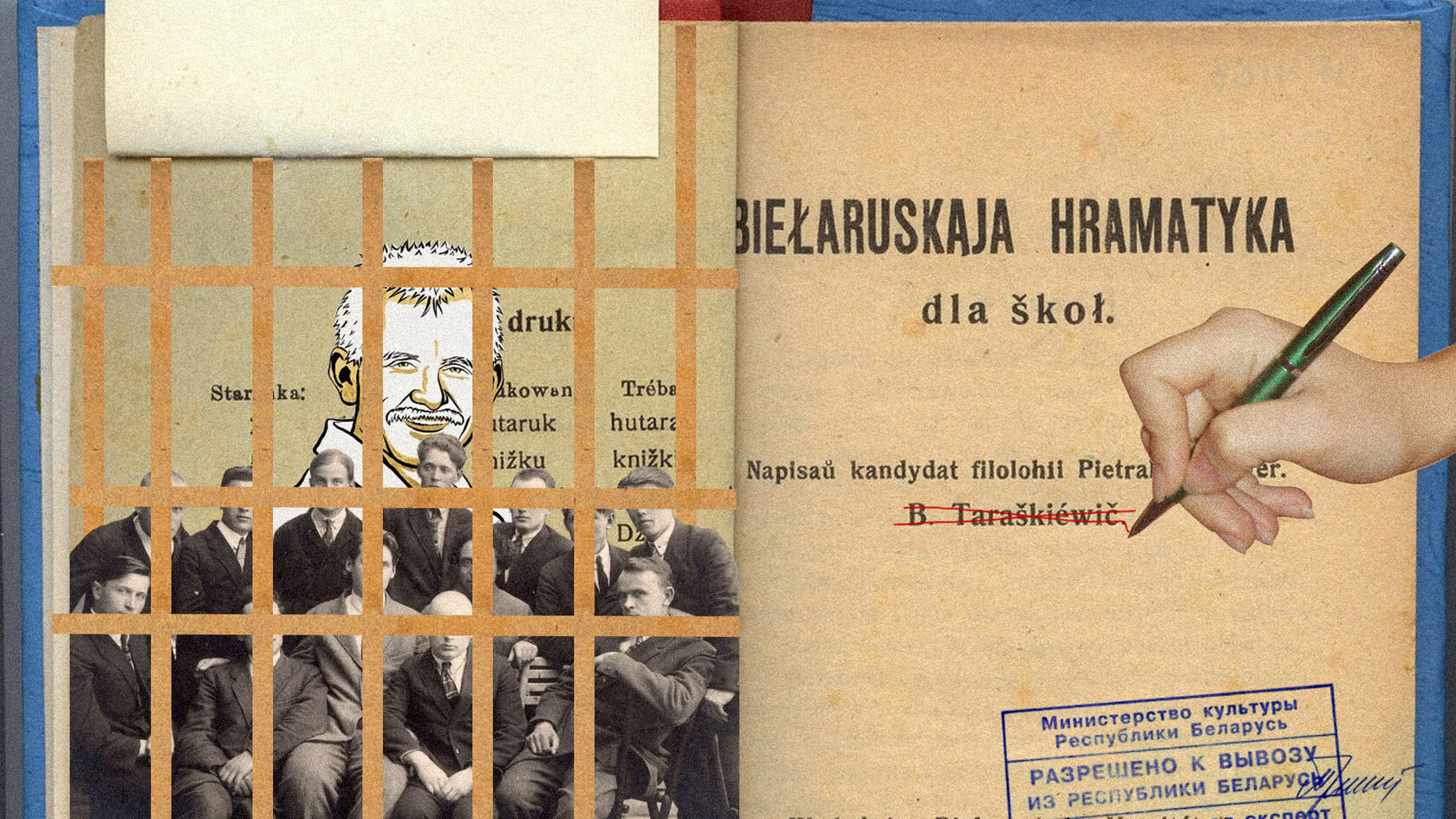

Comeback: Belarusian literature in search of new identity

The Main Trends of the Season:

“inside”

- continuation of physical and symbolic purge of the literary sphere by security forces and ideologists;

- shrinking of the literary life to the format of flat meetings and zoom conferences while public gatherings are criminalised;

- vigorous activity of pro-government literary institutions to “turn over a new leaf”;

- slow for now but steady reactivation of “great Russian culture” in Belarus amid Kremlin’s imperial rhetoric and Russia’s military aggression in Ukraine based on russification ideas;

- “wallenrodism” – a strategy of collaboration with the regime to preserve national heritage.

“outside”

- further increase in demand for literature in Belarusian as identity building material, establishment of new publishing houses;

- consolidation of authors and their readers around new centres of book culture and literary events abroad;

- increasing importance of pro-Belarusian educational components among “those who left”.

The Map of Meanings

The strategic task set before the authors of this review, first of all by themselves, is to comprehend the full range of events in national literature both in Belarus and abroad, giving the picture integrity, at least within the limits of expert analysis. The specified format requires accurate, clear, sharp and provocative evaluations with elements of hype and the ability to explain the essence of things to an audience far from the literary world. Therefore, the review of the autumn events in Belarusian literary life will begin with the situation in Belarus itself.

While outside the processes related to Belarusian writing and book publishing become stronger and more structured, forcing people to choose expressions and rent tuxedos and evening dresses, inside the freaking Armageddon continues, which does not spare emotions, epithets, or extreme metaphors.

Recording in Progress: rules of moving (forward)

The political and economic agenda has significantly worsened the situation of books and their authors in Belarus. The October 6 decree “on the inadmissibility of price increases” affected bookshops and publishing houses, as books were among the goods, the “incorrect” price of which could cause traders’ imprisonment. For some time, bookshops even refused to accept new books for sale.

At the same time, the June 22 decree came into effect, which enacted draconian measures regulating cultural space. The decree required organizers of events, including literary events, to register in the Ministry of Culture register and when planning an event, submit participants and scripts for approval and provide a free seat for a supervising official. But this new decree does not seem to apply to state institutions.

Some readings announced for September and November were cancelled after a phone call. Others were organized by certain companies on the condition that the organizers would not post announcements anywhere. Public readings are now no different from the good old “flat meetings”. In fact, all interactions between creative people inside the country came down to this format. Collecting general statistics or reviewing this activity even to keep it in a drawer for the time being is technically impossible today. Therefore, documenting these events privately (diary entries, photo-, audio- and video archives) is a good idea for winter evenings for “those who stayed”. A relatively new and well-tested during the coronavirus option for literature is online: zoom parties, video lectures, video interviews and podcasts (all these are actively used, for example, by the Belarusian Collegium, as well as other communities or book bloggers who stay in Belarus). In November, the online School for Young Writers started. In a word, what was streamed remains.

Collaboration: Not Just Business

The continuation of symbolic and physical purge of the literary sphere is a steady trend, or rather a flaming disaster of the season. In October, the books “Homeland” by Uładzimir Arłoŭ and Pavieł Tatarnikaŭ and “The Ballad of a Little Tugboat”, a Belarusian translation of a children’s poem by Joseph Brodsky, were deemed extremist. Both books, it seems, for white-red-white elements in the illustrations. Images of Natalla Arsieńnieva, Łarysa Hienijuš, the Łuckievič brothers and other Belarusian national heroes disappeared from the territory near Anatol Bieły’s private museum in Staryja Darohi after a call from a propagandist. Dismissals and contract terminations of “unreliable” employees in state cultural institutions do not stop. The Academy of Sciences, including its humanitarian institutes, was raided and searched in early November.

You will laugh through your tears, but there are still “meetings with the beautiful” on the scorched field. In October and November, creative meetings were held by Raisa Baravikova (in the “Book Club” – a new bookshop of the pro-government Union of Writers) and Taćciana Siviec (in Maksim Bahdanovič Literary Museum). Leanid Drańko-Majsiuk and Alena Brava were allowed into educational institutions. On September 29, an impressive circle of poets presented Belarusian translations of Chinese poetry in Maksim Bahdanovič Literary Museum. The above mentioned talented authors have demonstrated loyalty to the authorities in exchange for positions or access to the audience before. Now, with their delicate hand, “a new leaf is being turned over”. But a leaf written with lead ink is heavy. Therefore, it can be anticipated that the renewal of the social contract will soon be offered to a larger number of more or less talented creators.

In the structures that are gradually losing fans of the craft (what else can you call people who agree to work as hard as possible for such salaries?) among those who have not (yet) fallen victim to the “purges”, the sentiments of “wallenrodism” are popular. The strategy of cooperation with enemy forces to save the homeland was described by Adam Mickievič in the poem “Konrad Wallenrod” as early as 1825 and for almost a century became a scenario of survival for the inhabitants of Lithuania, Poland and Belarus under the Russian rule. This tactic is being quickly recalled in Belarus now.

Today’s “wallenrods” from culture set heroic goals for themselves: to preserve documents, archives and other material resources in Belarusian state institutions. And among other things, to organize at least some decent events in free venues (because there is a serious cultural hunger in the country). During the future blamestorming it will be very easy to confuse “wallenrods” with “collaborators”. It appears the verdict in each case will be individual.

So, the word “collaboration”, beloved by art managers, sparkled with long-forgotten colours when it became known about a new “Cultural Marathon” organized in schools in Minsk and funded by the Russian Federation. This long-standing trend in itself (the invasion of “Russian world” has never stopped in our country) is notable for the fact that the civil society finally saw a problem in it. But the most odious precedent of “collaboration” is, of course, the cultural and patriotic competition“First among equals”, which the BSU Lyceum conducts together with the KGB. Among the six nominations there is also a literary one.

Under the pressure of all these circumstances, the academic emigration of Belarusian-centric humanitarians is getting new incentives. Even more so there is a place for good specialists.

The most important events “outside” this autumn

From September 30 to October 2, the 10th International Congress of Belarusian Studies took place. Responding to the challenges of the times, the Congress updated its format, supplementing research cooperation with presentations of historical and fiction literature. In general, literary life outside the borders of Belarus is becoming noticeably academic, and topics connected with national and local history are becoming the most popular among those interested in books in Belarusian: “Coffee with a Historian” in Belarusian Youth Hub in Warsaw, Beer&History historical club in Bialystok. Another popular genre is children’s literature. Belarusians of all generations study.

On October 7, along with Russian and Ukrainian human rights activists, publicist Aleś Bialacki, the imprisoned leader of the “Viasna” human rights centre, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. At the same time, it became known that the author’s book was being prepared, the materials for which he managed to send from behind bars. The book is dedicated to the creation of Maksim Bahdanovič Literary Museum in the early 1990s and tells the story of how the employees of the Museum evolved into human rights activists. Someone had to document the protests of 1996, explains the author of the prison notes. And documenting and archiving is just the task for a museum worker.

As expected, the “Night of the Shot Poets” from October 29 to 30 became a significant date in the new Belarusian calendar. Actionism of Źmicier Daškievič (today he is a political prisoner behind bars), who since 2017 organized poetic and musical rallies in Kurapaty on October 29, and the 2017 multimedia project “(Not)shot” (“(Не)расстраляныя”) started the ritual five years ago.

Poetry readings, lectures, street actions were held in more than 20 countries: dozens of Belarusians abroad contributed to honouring the memory of the repressed Belarusian artists.

Modern writers in exile, who took on the mission of being educational mediums, organized and hosted many events of the “Night of the Shot Poets“. Literary bloggers and social activists dedicated social media posts to victims of repressions, often using the date as an opportunity to mention how Stalin’s terror affected their own family.

At the same time, the formation of a new Belarusian literary canon can be observed. It is noteworthy that out of more than 100 intellectuals who were killed, just the poets became the icons (in the “(Not)shot” project, sacredness is reflected in the number of figures: 12 of them), which once again testifies to the great weight of the poetic word in Belarusian society. It is obvious that Belarusians around the world draw unequivocal parallels between 1937 and current events in their homeland.

And another thing. Without exception, all of the listed “outside” events took place with the active participation of artists from the “inside”, regardless of technical obstacles (for example, Lithuania refused to issue visas to the participants of the Congress of Belarusian Studies from Belarus). So the unity of our cultural field, at least in literature, is preserved, despite everything, and this is a noteworthy fact.

- The rapid growth of Belarusian literary initiatives abroad risks to reach the glass ceiling soon, because writing and book publishing are subsidised crafts and it is difficult to achieve self-sufficiency. At the same time, it is clear that European funds do not see the support of Belarusian book publishing as a priority, and state resources are surely and perhaps for a long time unavailable to independent projects. A renaissance is impossible without the understanding that investing in Belarusian culture is the matter for Belarusians themselves to ensure a free and secure future.

- A clear public demand for the creation of a Belarusian national university in exile can be noted (despite the addition of subjects in Belarusian in the new semester, EHU in Vilnius is not perceived as such). The hope is that the demand will finally create its own supply.

- Existential suspense reigns inside Belarus. For literature and writers, there are preconditions for the repetition of virtually every negative scenario of the last century: bullying, physical oppression, marginalisation with the help of the Russian bayonet, the Russian church, the Russian school with the active participation of the new Mikita Znosaks (a negative character from Janka Kupała’s play “Tutejšyja” who could easily adapt to any new regime). But in fact, in all the public literary formats allowed today, there is sincerity, secret mutual support and Aesopian language, which cannot but instil hope.

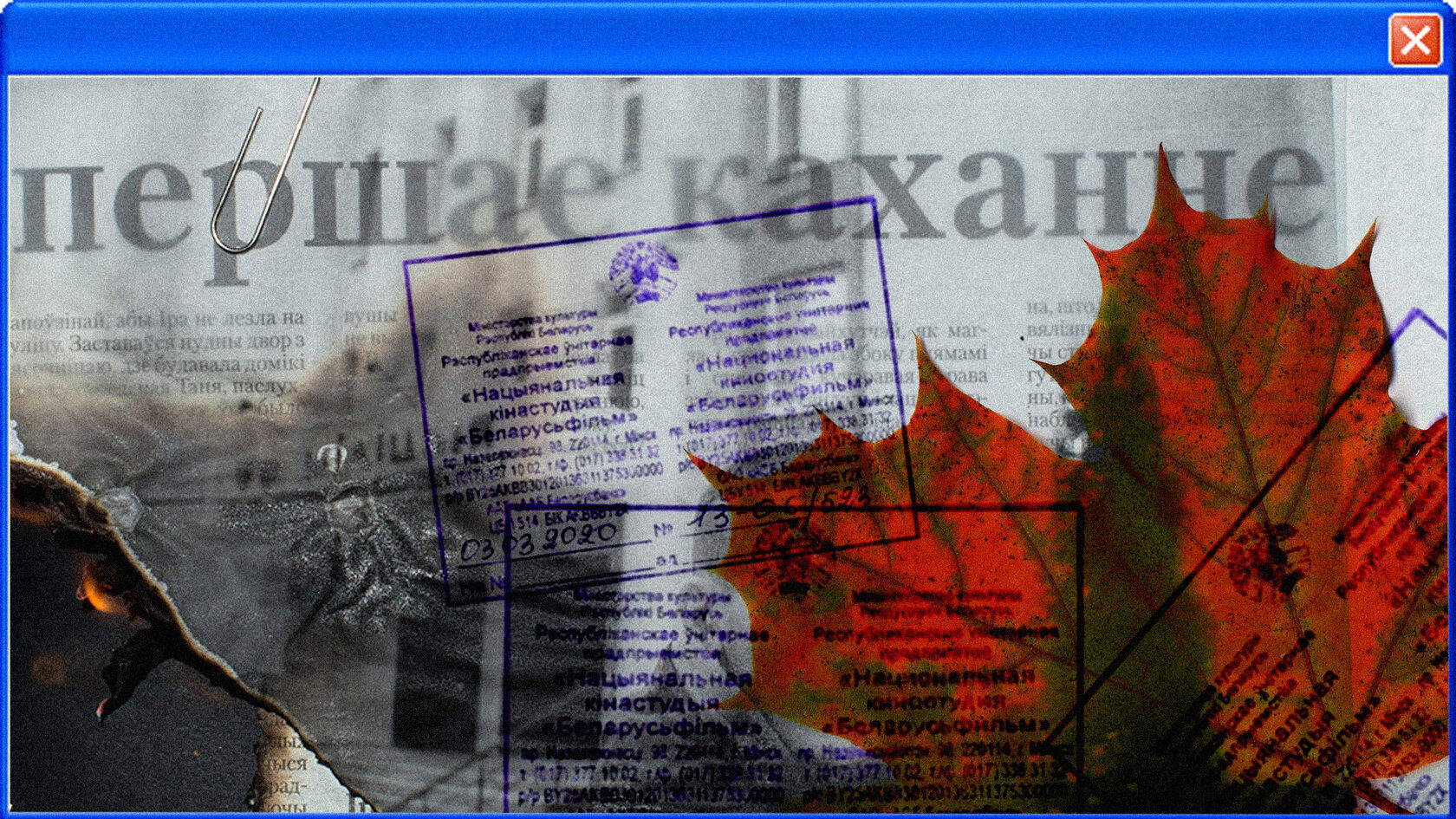

The most important of the arts: cinema as a bureaucratic project

The Main Trends of the Season:

- bureaucratic activities around the cinema increased dramatically;

- attempts are being made to transform the official cinema by eliminating everything “unofficial”;

- offline cinema distribution in the country is the sphere of state cinema, while online is becoming the space of non-state cinema.

Mind map

These two months were so quiet for Belarusian cinema that the creaking of the bureaucratic process could be heard at its very bottom. It determined the essence of those two months, creating a feeling of déjà vu of 2013, when non-state cinema had just emerged and here and there made small holes in the solid state narrative with rare news about a new film created by a lone author with a minimal budget. It remains to be seen if this process will be able to drive Belarusian cinema into a long and rather hopeless trend.

The process goes on

Back at the end of August, the Ministry of Culture announced a student short film explication competition (note the nominations – “My Native Corner”, “First Love” and “Urban Legends”), as well as a synopsis competition for a film about Alaksandr Prakapienka, a football player of “Dinamo Minsk”. Such contests quietly happen from time to time just to continue a bureaucratic ritual. But this time it was moved into the category of major initiatives.

At the same time, the first meeting of the organizing committee of the “Listapad” film festival was held, headed by – you should concentrate now – Vice Prime Minister Ihar Pietryšenka. Never before had the film festival been such a big state affair or required the presence of a vice prime minister.

After that, a panel on cinema and circus was held in the Ministry of Culture, where it was insistently stated that “Belarusfilm” studio was the “leader of domestic film production”. It was announced that there were 14 films at various stages of production there (which again indicates the close to zero capacity of the studio and the system), a couple of them were announced – at least a New Year’s comedy “Olivier” co-produced with Russia.

Then there were a number of Days of Belarusian Cinema abroad. Abroad means in Russia. On September 14, Days of Belarusian Cinema took place in Kursk, then in Fergana, and then in Moscow. New feature films of 2022, “Detonation” and “10 Lives of Miadźviedź”, were also announced there. If “10 Lives of Miadźviedź” was indeed shown in Fergana (and there is no confirmation of that), then here is an alarming precedent for you: the international premiere is significantly ahead of the national premiere (or may even replace it). Officials would like to think that it means “entering the international arena” again. But no: it is just cleaning up the national space again.

On September 23, a presidential art grants competition, including film grants, was announced. How it ended and whether it ended is still unknown.

On September 28, Prosecutor General Andrej Švied visited “Belarusfilm” in connection with the launch of the “We Are One” project about Western Belarus. Earlier, in July, Prime Minister Raman Hałoŭčanka also visited the film studio for the same reason. And there was a time when films did not require the participation of officials of this level. The filming started on October 5.

A small festival wave followed: at the beginning of October, a bureaucratic documentary film festival of the CIS countries “Eurasia.Doc” took place in Minsk and was covered by the state media quite unenthusiastically. On October 12, the slogan of the “Listapad” film festival was loudly and significantly announced – as we remember, “Истинные ценности / Сапраўдныя каштоўнасці” (“True values”). That’s right: bilingual, first in Russian and with a slash. If last year “Listapad” was still quite confused, then this year it found a sure path and announced every step along it with soldierly zeal. But “Listapad” will be discussed in more detail next time. At the end of October in Mahilioŭ, modestly and without attracting anyone’s attention, the animation festival “Animaytion” (“Анімаёўка” in Belarusian) took place.

Finally, there was a small wave connected with the films themselves. “Belarusfilm” announced the shooting of a documentary film about the life of Jakub Kołas during the war, then started shootingthe film “We are one” and at the end of October announced the start of shooting the film “A Letter of Waiting” by Alaksandr Jafremaŭ, one of the authors of the new Constitution and the stated creative director of the film “We are one”.

Admittedly, there were too many high-profile events for two months – and a lot of formats of the same administrative activity. They are united by their clear intention to create the illusion of complete control over the cinema. Let’s pay tribute to the effort: we saw how much administrative effort is put into making sure that officials-in-charge of the cinema do their job.

It split up

A new attempt to return the cinema exclusively to its ideological part, fused with the bureaucratic apparatus, is also evident here: “the party marks the way – filmmakers pave it.” The actual goal is to transform the official culture, which fully serves the requests of the state and caters for members of the bureaucratic system. Well, all conditions have been created for this. The first and foremost is that the cinema, uncontrolled by the bureaucratic apparatus, has been pushed out of the country physically or has gone underground.

And now, as before, it creates these small holes in the solid state narrative about the cinema: the film “Belarus 23.34” by Taćciana Śvirepa was nominated for an award at the Jihlava International Documentary Film Festival, “A Date in Minsk” by Mikita Łaŭrecki won the DocLisboa festival, “Live” by Mara Tamkovič won the festival in Gdynia.

The air in the cinema has become so clear that there is even news as if from the past: a Belarusian is making a film with his own money and has released a trailer. This time it’s a film about the war in Ukraine.

Such a contrast between the official and the unofficial, the centralised and the decentralised, the vertical and the horizontal held Belarusian cinema for almost a decade. And now, after a year’s lull, it is clearly trying to recover. Only there is one significant factor: single authors are mostly emigrants now as well.

But the time for the wave of emigrant cinema has not come yet.

This new scattered state must be named somehow. After all, we have what we have – an impeccably empty space inside the country, where the cinema exists in four aggregate states: an opening of a film production competition, an announcement of production, a start of filming and a presentation dedicated to just another official date of little significance. The fifth state is a presentation abroad (which almost automatically means that it will not be shown in the country).

Perhaps this is exactly what the beginning of the split into domestic and foreign cinema looks like. One thing is clear: the internal product should become fully approved by the state.

Escaping online

There is nowhere to escape from this closed space, except online. It seems that the main events of domestic cinema will take place there in the near future. There is already the first case: the video production festival “Hliadač”, which was supposed to take place offline in Minsk and was cancelled the day before the start. And on September 23 and 24, it took place online: 37 fiction and documentary short films in two streams and a chat as a space of contact between authors and viewers with the possibility of instantly donating to your favourite authors.

Unconditioned at last by the bureaucratic system, it rejects hierarchy, centralization and other features of state power structures. And builds, like the Cinema Perpetuum Mobile festival before it, horizontal connections and an open community. Note the Belarusian Latin alphabet in the title: as can be seen in the case of “Listapad”, the language issue is fundamental in the cinema this year.

Going online confirms that there is now a significant difference between a physical presence and an online presence. The online cinema space is still officially labelled if not as marginal, but as insignificant and, perhaps, amateurish. In any case, it is still “external”, “outside the borders” and uncontrolled – in this it has more luck than the media space. In a certain segment of the cinema, it can also mean freedom.

“Hliadač” defined online as a space of expression and self-identification outside the boundaries of the ubiquitous bureaucratic system. At the present time, this is a phenomenon and an act of bravery.

Searching for a safe way of expression

Bureaucracy would, of course, be happy to exist silently and fruitlessly. But in the cinema, the lack of expression is also an expression. All the actions of the official cinema prove that it is busy searching for the safest possible way of expression, preferably synonymous with silence.

The only new feature film officially released in the country this autumn and in the last two years is the mentioned “Detonation” by Ivan Paŭłaŭ, which gives certain ideas about currently allowed screen discourse.

It is not difficult to notice that it is safe precisely because it coincides with the Year of Historical Memory. In Minsk, “Detonation” was shown together with the ATN stories (in cooperation with the KGB) “Without a statute of limitations” – about the “genocide of the Belarusian people during the war”. In Žlobin, for example, it was instrumental on the Day of National Unity together with “A triangle letter from the front” master classes, “Historical memory and truth” banners, soldier’s porridge and other attributes of the state cosplay of the victory – despite the fact that the film is about an undeniably peaceful life and post-war mine clearing in Belarus.

Notably, in “Detonation” an image of a shapeshifter character (a positive hero who turns out to be a negative one) is reborn after long oblivion: an Osoaviakhim teacher, who turned out to be a member of a gang and took part in a shooting of civilians. Since the 1930s, the motif of a shapeshifter has saved Belarusian cinema while it was avoiding direct expressions. And paranoia apparently still looks like the most economical way of understanding reality.

This avoidance is made even more poignant by the fact that the film – then called “Flame under the ashes” – was originally planned to be not at all about post-war mine clearing, but about the fire in the NKGB club in 1946. During the production, the series about the fire turned into a series about current and post-war deminers’ cooperation with – get ready – the Mine Action Centre of the Ministry of Defense, and from it into a full-length film exclusively about the post-war period.

It looks like a good story about chasing a safe way of expression. A crucial point in it is the cooperation with the Ministry of Defense. Now films again have to be justified by the need of important state agencies. And in the near future, one should not expect anything, except for the amplified – not sly, like in the herbivorous 2010s – but downright ceremonial servility.

In such circumstances, we will once again look to amateur cinema for a long time. If only because of the fact that at the “Hliadač” festival it managed to resonate with the emotional reality, which we now struggle to understand and which official cinema is stubbornly squeezing into the marginal space, all the while remaining within its characteristic themes of loneliness, splitting (and bifurcation) and disintegration and in the captivity of dim plots and images.

Conclusions and predictions

With the cleared internal offline cinema space, there is only the online format to rely on. It can be expected to reduce the division between domestic and emigrant cinema. And the community will be able to retain at least the understanding of the Belarusian cinema space, which was established at the time by the “Listapad” national contest: Belarus as a point of contact of identities regardless of place of residence and production.

The only positive news is the opening of the renovated “Belarus” cinema in Stoŭbcy with a very modern public space. It looks like a challenge to the bureaucratized culture, which perceives the grassroots movement as a danger. So if a cinema can’t be a cinema, let it be a modern venue for spontaneous local networking for new generations. This is at least something future-related.

Belarusian theatre: “dark times”

The Main Trends of the Season:

- The state cultural policy leads to narrowing of Belarusian theatrical space and displacement of managers with different views;

- Almost total annihilation of Belarusian theatrical critique has led to the impossibility of public expert assessment of performances and creation of even basic hierarchy built on the artistic principles that existed before 2020;

- Censoring of performances continues, hiring decisions are made on the Ministry of Culture level which further enhances state intervention in the theatrical sphere;

- Certain Belarusian artists continue successful integration into the Western European theatre system. Those who have experience of working abroad or work as a part of certain organizations have an advantage. Lack of experience when trying to sail freely makes it difficult for some artists.

A discount store in the place of an iconic venue

In the new theatre season Belarusian theatrical space continues to shrink both figuratively and literally.

During the second part of the 2010s OK16 was one of the iconic venues – performances organized by “Art Corporation” were held there as well as OK16’s own productions. After the liquidation of both enterprises a private ballet school was based there. But now everything has “fallen into place”: a Russian chain discount store will open in the building. A symbolic event which demonstrates the city government’s attitude to theatre and culture.

Besides that Belarus has nearly lost one of the national theatre companies. As it became known, the actors of Minsk Regional Puppet Theatre “Batlejka” in Maladziečna were informed at a meeting that from January 1, 2023 they will be a branch of a local drama theatre. No one could clearly explain the reasons for this merger. We believe the desire to save money and to report about optimization was the reason for that.

There was no logic whatsoever in this decision. The specifics of a drama theatre and a puppet theatre are absolutely different. Football and hockey clubs in one town might have been merged just as well since both football and hockey are sports. On a more serious note, that kind of merger would in fact have led to the following: drama actors would continue to perform on the stage while “Batlejka” would be obliged to give offsite performances in schools which could have resulted in its sharp decline and possibly liquidation.

Fortunately, this idea was unexpectedly dropped because of a legal technicality: by law a prospective branch should be in a different locality. This saved “Batlejka”. To be fair, there is no certainty that similar plans for other regional theatres will not emerge in the future. Even though the number of state theatre companies is less than 30 – a tiny amount for a 10-million country.

Meanwhile professionals continue leaving these companies. Jaŭhien Klimakoŭ, who was the head of the Puppet Theatre in Minsk since 1985, resigned from the theatre. He and Alaksiej Lalaŭski were almost a perfect team of a head of a theatre and a chief director in Belarusian realities. It was Klimakoŭ who advanced organization and conducting of the Belarusian International Festival of Puppet Theatre which was held in Minsk since the 1990s (now it is on hold). Officially he resigned of his own accord but we could only guess at the independence of such a decision.

Incidentally, Klimakoŭ was one of the alumni of a famous course of directors in the Theatre and Art Institute (present-day the Academy of Arts) as far back as the Soviet period which was an obviously progressive event then.

Now such specialists are not prepared at universities and random people often hold managerial positions in theatres. At the time of this writing, Klimakoŭ’s replacement has not been appointed.

Censorship and almost serfdom

The new season started with new fault-finding in performances. This time Emmerich Kálmán’s classical operetta “The Duchess of Chicago” fell victim to state officials. After the preview in September attended by officials from the department of culture of Minsk City Executive Committee, the Musical Theatre announced that the premiere was cancelled “due to technical reasons”.

It would appear that “The Duchess of Chicago” is a political satire on European and American realities of the 1920s. But apparently there were similarities with the current situation. According to the theatre employees, the officials did not like the jokes about the start of the war with Japan, homosexual characters and generally favourable depiction of America in the operetta.

The theatre management admitted having to get rid of some characters and certain mise-en-scènes which resulted in the performance being 20 minutes shorter. “Now the plot will not have any dual interpretations” said Adam Murzič, the art director of the theatre. After that the officials finally allowed the performance of “The Dutchess”.

Of course this was not the only new production this autumn – there were performances in other theatres. But years later future researchers will face huge problems trying to analyze them and will probably define them as “dark times”. One of their manifestations is almost total disappearance of public expert review of performances as a result of specialists fired, websites which were the platforms for publications closed, festivals stopped and finally emigration of numerous cultural figures.

Before that it manifested in sparse reviews and feedbacks in social networks, existence of selection for the Belarusian program of ТЕАРТ or “M@rt.кантакт”. But the latter festival has changed leadership and lost its reputation. ТЕАРТ has been closed. The number of reviews dropped sharply. The national theatrical critique has been almost completely wiped out.

There are small remnants of it but texts that are sometimes published in state-run media contain almost no negative reviews. At best the true state of things can be revealed in a paragraph in the middle of the text or even a couple of sentences well hidden in the author’s discourse. There one can briefly enumerate key flaws that call into question all above mentioned merits. At worst there is not even that.

So without direct viewing (only the Theatre of Belarusian Drama streams new productions on VOKA service, some performances are recorded and broadcast on the channel “Belarus 5”) it is impossible to form even an approximate impression about a performance. Positive public review of each and every production makes it impossible to create even a basic system of quality hierarchy based on the artistic principles (existed prior to 2020).

These years will be called “dark times” for a number of other reasons. One of them is backstage decision making and a so-called “phone law”. Officials took full control over the personnel policy: now to get a job in a theatre a person needs not only a letter of recommendation from a previous job. According to our information, an interview with Iryna Dryha, the “grey cardinal” of the Ministry of Culture, is required. A rejection on her part can put a stop to further employment and such practices remind of the “best” traditions of serf theatres.

Europe is waiting: La Scala, Warsaw, Berlin

The national theatre continued developing outside Belarus as well. The biggest sensation occurred in Italy: Vital Aleksijonak from Belarus became the music director and conductor of “The Little Prince” opera, which premiered in the famous La Scala Theatre in Milan.

Belarusian singers had performed on the world’s best stages before, although their number was low. For example, over the years only 4 Belarusians have sung in the Metropolitan Opera in New York: Kaciaryna Siemiančuk and Iryna Hardziej, lead singers in the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, Aksana Vołkava, a star of the Opera Theatre in Minsk, and Alaksandr Rasłaviec, a lead singer in the Hamburg State Opera. So every invitation like that is a major event. It was the first time a company of such a scale had taken an interest in a Belarusian conductor. In fact, after the premiere in Milan Aleksijonak took a job in the German Opera on the Rhine in Dusseldorf. This opens new opportunities for him.

Director Jura Dzivakoŭ, well-known mainly in Belarus until now, continues gaining reputation in Poland. His production “Naścia” became a part of the repertoire of the Powszechny Theatre in Warsaw. Initially there was a draft based on a novella by a Russian writer Vladimir Sorokin. It was shown in December, 2021 and after that the management had to decide whether to keep “Naścia” in the repertoire. As a result a fully fledged premiere took place in April, 2022. The production is shown often. The tickets for January, 2023 are already on sale. The production cast includes actors from Poland, Ukraine and Belarus (among the Belarusians – Kaciaryna Jermałovič, Darja Novik, Volha Kałakolcava and Mikałaj Stońka).

Among the previous successful projects we should mention the premiere of a performance / techno rave party “P for Pischevsky”. It also took place in April, 2022 only not in Warsaw but in Berlin, in the venue of HAU2 Hebbel am Ufer. Later, in October, a 15-minute video about working on the project was released.

“P for Pischevsky” is a joint project between the HUNCHtheatre Belarus (Minsk) and CHEAP (Berlin). It is based on the story of Michaił Piščeŭski, who was attacked after a gay-party in Minsk in 2014, and the court case of his murderer. The production was directed by Uładzimir Ščerbań from Belarus. Among the cast there were representatives from four countries – the USA, Great Britain, Germany and Belarus. The latter was represented by Hleb Kavalski, a DJ and an actor, and Rusia (Maryna Šukiurava), a musician and a singer.

Theatre outside the country: new war, old repression

Belarusian theatre companies abroad released a couple of new productions.

The Belarus Free Theatre presented a documentary production “Afterchildhood” (“Паслядзяцінства”) in Warsaw in September. This is 8 stories of teenagers who moved to Poland with their parents fleeing political repression in Belarus and/or the war in Ukraine. The characters who were deprived of home and to a certain extent of childhood were played by the teenagers themselves. “They wrote the texts themselves, drew the poster themselves and acted themselves – my job as a director was just to unite them and direct them to avoid offending adults and parents. To my mind, it is Turgenev’s “Fathers and Sons”, only in real life. It is a conversation between an older and a younger generations” – said the director Pavieł Haradnicki.

The August Theatre – actors from Hrodna who united around the director Andrius Darela under the roof of the Old Theatre of Vilnius – released a documentary production “A Performance That Never Took Place” in September. It is based on the documentary accounts about life in Mariupol occupied by Russia. These accounts were posted daily on Facebook by Nadzieja Sucharukava, a local journalist.

The play starts in the theatre’s basement, continues in the corridors and only then actually goes on the stage. The building has long been in need of major repair but this actually worked out great for the general idea: within the old walls it was possible to fully submerge into the material, viewers could really feel themselves in Mariupol. Thanks to the “journey” along the corridors with their sharp turns there was a feeling of a bomb shelter. And also a labyrinth one should find a way out of.

The actresses (among others Nateła Białuhina and Natalla Lavonava from Belarus) took turns talking to the viewers (there were only about 20 of them, as many as physically possible), stopped in certain places and spoke about another act of aggression and on the walls nearby one could read excerpts from the posts written by people from Mariupol, such as “I felt more comfortable in the basement among the dead than among the living”, or “Silence. Rehearsal in progress” – in Mariupol only those who were in the basement survived the first bombing, everyone on the stage died.

One of the earlier projects of the August Theatre “What for?” was dedicated to the “night of the shot poets” (mass execution of Belarusians in 1937 when more than 100 intellectuals were shot). This – and to be more exact, the poetry in times of repression in general – is the basis of the poetic performance “37-22” (directed by Andrej Saŭčanka) presented in Białystok by “Kupalaŭcy” theatre company.

The “What for?” project came out educational and moving. But due to the lack of high-quality dramatic composition there was an impression that each of the participants tried to express their own pain, which led to everything coming out jumbled. Nevertheless the production had the drive, rhythm and nerve, so it looked well.

“37-22” in comparison lacked energy. The declared storyline (the confrontation between poets and officials) at some point got lost. Because of the very similar style of the pieces recited in the finest tradition of the Kupalaŭski Theatre by actors-officials and actors-poets, the division between “good” and “bad” characters lost meaning and later utterly disappeared. The extremely poor lighting did no justice to the scenography and instead of a good picture showed non-existent bags under the actors’ eyes. As a result the best part of “37-22” was the music by Eryk Arłoŭ-Šymkus.

In one of the interviews actress Valancina Harcujeva said that “Kupalaŭcy” theatre company would try to establish a permanent theatre in Warsaw. Hopefully “37-22” will eventually meet the high standard of the company.

Conclusions and predictions

- The division inside the Belarusian theatre deepens.

- Theatre companies in Belarus still live in the Soviet frame of reference characterized by state interference and censorship in almost every area – from hiring personnel and choosing a title for a show to final (dis)approval of a production and its always positive review in mass media. In such circumstances high-quality productions are possible: most of the staff continue working and the degree of interference depends on every individual official. But any success is achieved in spite of, not thanks to the described circumstances.

- Theatre companies in exile gradually expand their activities. By learning from their own mistakes they adapt to a new and unfamiliar system and create a further development strategy. With the exception of the August Theatre, which works with a repertory theatre, they mostly work as project theatres. How long and successful will their activities be? It will depend on a number of factors – importance of their work for Belarusian exiles and local public, funding (culture supporting grants or their own earnings) and, of course, the artistic quality of productions.

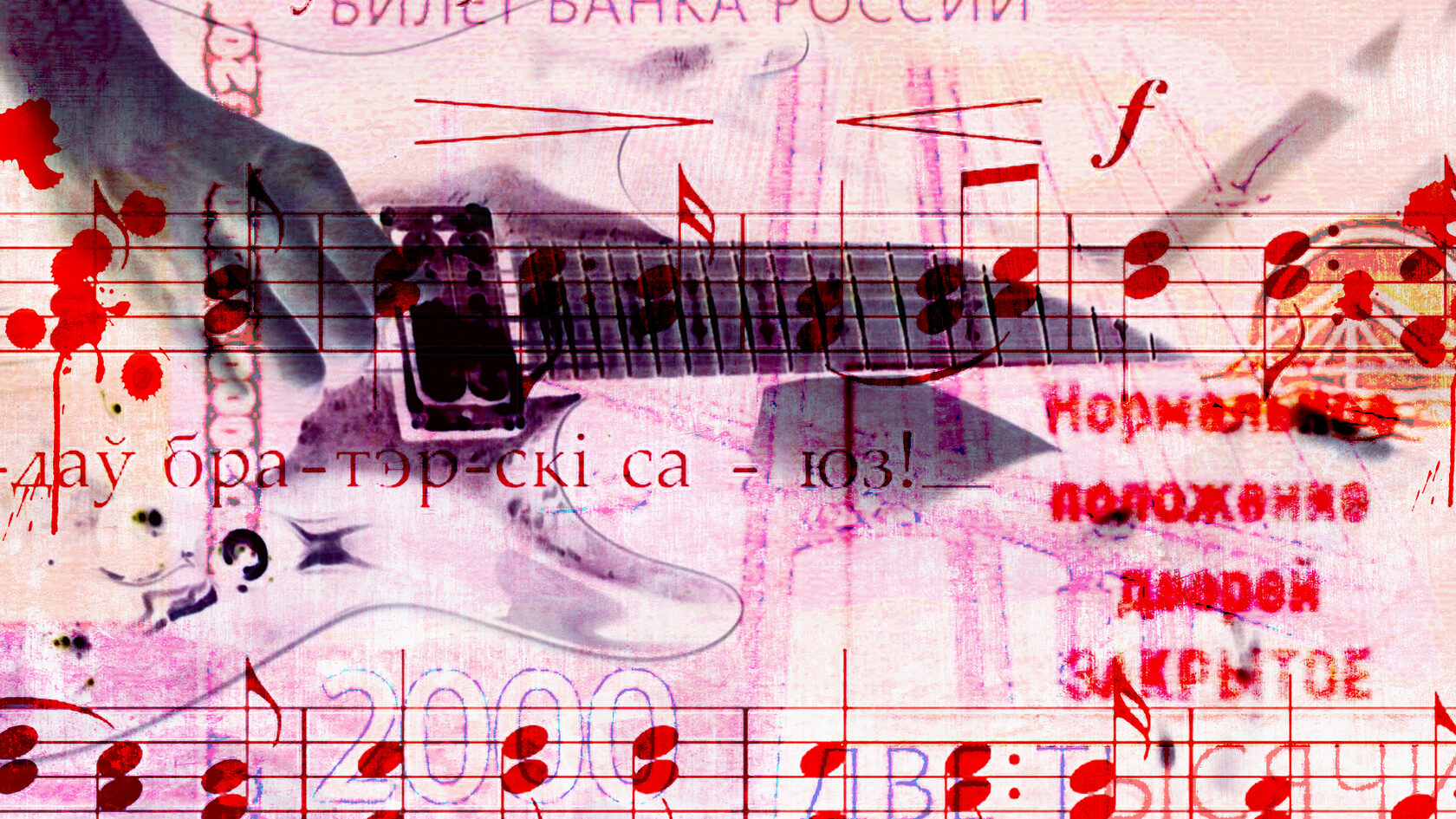

Pop & rock. Cancellation and battles for online success

Main Trends of the Season

- Cancellation of artists is gaining momentum: the musical space is shaped by both the state policy of banning everything Belarusian and the “public control” of haters.

- Detentions of musicians continue: Tor Band and Litesound were put behind bars. In total, since August 2020, the Belarusian Council for Culture has recorded 214 facts of repression against musicians. State terror destroys the space of creation of meanings, but is unable to offer anything in return.

- Belarusian musicians gather large audiences in Europe and give successful concerts overseas. The diaspora now exists in an active phase. But how much time does an artist have?

- The Belarusian language is in trend, but it lacks quality: sometimes lyrics resemble a mechanical Google translation.

The map of meanings

Era of cancellation: cancelling and hiding

It is interesting and sad at the same time to live in the era of total cancellation. What is happening now sometimes resembles a wild hunt with nuclear weapons: no winners, no losers – only the remains of victims of prohibitions.

On the one hand, Belarusian music within the country remains deep underground and fully exists only outside the territory of despair: when a rare Belarusian band goes on tour to other countries and gets a chance to earn money there.

The state has cancelled independent Belarusian music. Now old and young Russian artists arrive here in unlimited numbers. The cultural landscape has completely changed, and hearing the Belarusian language at a concert in Minsk today is a real challenge. Instead of Volskі – Leps, instead of Vajciuškievič – Viktor Korolev, instead of Naviband – Lesha Svik.

On the other hand, Belarusian community carefully observes public performances of its artists. Every statement and every step are discussed on social networks, and in particularly clinical cases opinion leaders try to edit the reality and even the track list. A vivid example is singer Palina, who at a concert in Warsaw performed the song “Облака – белогривые лошадки” and received a wave of hate from Twitter users who were dissatisfied with the “Russian” repertoire.

Not all Belarusian artists can withstand this consistency check. For example, “ЛСП” band, which in the spring postponed its Russian tour due to the impossibility to perform in such circumstances, and the leader of the band spoke out against the war, successfully toured Russian cities in October and November. What has changed since spring? The question is rhetorical. The war is still going on.

Not all band members took part in this tour. For example, the guitarist of the Russian band “Мумий тролль” played with “ЛСП” as a session player. When information about the tour became public, the musicians simply removed the concert schedule from the official website but did not comment on the situation.

Modern artists must select their repertoire carefully and be good at geography. Rhetoric courses are optional.

Repressions continue

Repressions against musicians continue. Since August 2020, the Belarusian Council for Culture has recorded 214 facts of repression against musicians: concert bans, harassment, imprisonment. A recent example is the detention of members of the completely trivial pop band Litesound: a “repentant” video with the musicians was recorded and it was noted that unregistered weapons were found in their possession. This is how the state takes revenge on artists who received something from it at one time but turned out to be “unreliable”. It is similar to the behaviour of an offended child who has not yet developed emotional intelligence. According to this logic, Belarus is a country of “ungrateful” artists who were allowed to work, but they do not work in the way the state needs.

Another striking example is the detention of the musicians of Tor Band from Rahačoŭ. In 2020 they recorded rock anthems, which eventually became one of the symbols of the protest. Tor Bandmembers were detained together with their wives, and they were not released after 15 days. It was reported that the security forces were also interested in everyone who took part in the filming of the band’s music videos, and also seized the Tor Band accounts and deleted all music videos with more than 5 million views in total. This is a state’s attempt to plug the hole in “our common boat” with a rag, and to wave away everyone who noticed that the boat was turned against the current.

Two members of Irdorath band and other Belarusian artists remain behind bars. Being an independent musician and continuing to live in Belarus is a serious risk. Being a Belarusian independent musician and touring Europe while living in Belarus is heroic. Many have put their projects on hold and live in inner emigration. Obvious examples are “Крама” and “Палац“, which do not have the opportunity to perform in Belarus but remain within its geographical borders. These bands are on pause, like many others. Only a few can afford working in conditions of inner emigration. As an example, the band Akute, which was blacklisted in 2020 but found the strength to release a new album, “Напалову тут”, while remaining in Belarus.

Others emigrated for real and collect their bands and equipment piece by piece, like Relikt and “J:Mopc“, or try to earn money and adjust to life in a foreign country in a different way: working in construction or in a shop during the week and touring on weekends – this is a new reality.

New Belarusian music: attempts of presence

After the protests of 2020, the art of resistance reached its peak: in just a few months, more than a hundred protest songs of varying degrees of quality were created. After that, there was a predictable decline: repression, forced emigration, and attempts to make a living did not contribute to the emergence of new and high-quality music. The same decline can be seen even now.

When it comes to successful examples, we can mention Akute‘s new album – “Напалову тут” [“Halfway here”] – in which the band returns to its guitar roots after an ambiguous experiment with electronic sound. Or Gregory Neko‘s quite successful experiment – a contemporary mix of electronics and jazz-like improvization, which sometimes resembles a currently popular London band The Comet Is Coming. A cool release by band “Союз” – a vivid homage to the Brazilian music of the 1970s with gentle melodies. The album, by the way, received a compliment from the American star Tyler The Creator. The album Hlybini by an accordionist Alaksandr Jasinski, a former member of the Fratrez and Bosae Sonca bands, should be mentioned: an interesting combination of progressive rock, experimental music and jazz, at least from the point of view of the use of the instrument.

But these are all quite well-known names. New Belarusian music lacks a fresh perspective and interesting ideas. On the one hand, this is the result of total state censorship. On the other hand, it is also a question of musical horizons of an artist when an initially secondary product is used as a reference. Thus, music parasitizes genre clichés and tries to conform to certain standards: it sounds either childishly naive or predictable and uninteresting. In the first case, there are timid reasons for optimism, in the second case, one can safely switch on the “grandpa” mode and dwell on the fact that Belarusian music is no longer the same.

In October, a popular TikTok artist kirkiimad released the album “Crowd of Krots”: a compilation of genre clichés of teenage pop music, decorated with a decent sound design. Another example: in September, a new track by a currently popular trio uniqe, nkeeei & Artem Shilovets was released – a song completely devoid of ideas but with 300,000 views on YouTube.

A new Belarusian musician dreams of getting into trends on TikTok or beating the YouTubealgorithms. This is a fight with artificial intelligence for the right to exist on the Internet. And the artistic value of expression here has completely secondary importance. For a beginner Belarusian artist deprived of media support, this is the only way to a potential listener. Design and survival tactics are in the first place, artistic value is a nice bonus.

At the same time, the Belarusian language is an important element of creative expression even for Russian-speaking artists. This is a legal expression of a position and a painless attempt to say something that supposedly cannot be said. For many musicians, this is a difficult philological experience, so it turns out to be inappropriate, to put it mildly. The lyrics of the songs are created based on the school course of Belarusian and Google, so they limp on both legs with Russian words and weak rhymes. The question of whether it is for better or for worse is debatable and does not require an answer.

A vivid example is the song “Дзікунка” (“Savage”) by a young singer Iva Sativa. This is an attempt to combine the Belarusian language and a fashionable beat, but the attempt is quite weak. It can be seen that in the artist’s mind, Belarusian culture is a clichéd image of grandmother’s singing about maidens and round dances, through which ridiculous lines appear: “Карацей кажучы, ну што б ты панімаў, гэта Беларусь, ёў, ацані запал” (“In short, well, so that you understand, this is Belarus, hey, check out the passion.”)

Belarusian bands: mobile triumphs

Popular Belarusian musicians find their audience outside the geographical borders of Belarus. Four times a year “Петля пристрастия” tours Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Germany, the Czech Republic, Cyprus and Georgia. Optionally – Austria and Armenia. Attendance at such concerts is much higher than before 2020, and this can easily be explained by mass emigration. Nizkiz and Naviband organize regular European tours.

Lavon Volski and “J:Mopc” band successfully toured the USA and gathered quite a large audience even in those cities where it seemed impossible before – Belarusian diasporas all over the world are very active. Belarusian concerts are a platform for starting self-identification and reflection, a territory for uniting according to nationality.

For popular bands, this is a great opportunity to attract a new active audience and earn money. On the other hand, young Belarusian projects are completely deprived of the possibility of a stage debut: there are simply no venues. Major media have crossed off the cultural and educational mission from their agenda and only watch famous artists. Niche music media have ceased to exist. There are several Telegram channels that write about new Belarusian music but their audience is very limited: the largest one has less than 2 thousand subscribers.

It is difficult to call the conditions for creating music favourable, the main task for an artist is to find an opportunity to reach listeners. And almost the only way for debutants here is to fight the algorithms of large social networks.

Conclusions and predictions

For some time, popular Belarusian musicians will have the opportunity to perform in front of a large audience, but this resource is, unfortunately, exhaustible. For those artists who live in Belarus, European tours can end at any moment – when the borders with the European Union are closed for good. Those who live outside the country can face the passivity of people, who will inevitably stop going to concerts en masse. First, it will be a reaction to studio passivity of Belarusian musicians. Second, endless tours will inevitably overfeed the audience.

The activity and quality of creative work of new Belarusian artists will decline. Now they do not have channels and venues for their broad presentation. Belarusian media only occasionally pay attention to artists and are completely passive in relation to culture.

Distribution of creative work is now a struggle with artificial intelligence for the right to exist: in such conditions, it is not about a unique product, but about compliance with certain standards.

The pressure of repression forces artists to censor themselves and carefully select messages to feel safe, while the public, in turn, expects bold actions and statements from opinion leaders. A perfect newsmaker in 2022 must be uncompromising and ready to sacrifice. But what will they get in return? A prime-time moment of fame that ends the next day, and the consequences can be disastrous. Artists have long assessed possible risks and are not ready to sacrifice.

Belarusian musicians are now under tremendous pressure. On the one hand – repression by the authorities, on the other – cancellation in case of unpopular steps and creativity manifestations. In such circumstances, an artist (if possible) usually puts creative activity on hold and engages in a more rewarding and profitable business.