Mice under a broom waiting for a wild hunt

Belarusian cinema: in limbo

Theatre: survival in Belarus, temporary renaissance abroad

Pop & Rock: summer game simulating the presence of the market

The Art: Inside and Beyond the Borders

Mice under a broom waiting for a wild hunt

The main trends of the season:

- continuation of the physical and symbolic purge of the literary process (inside);

- continuation of the relocation of the literary process outside Belarus;

- the crisis of professional literary criticism against the background of commercialization of Belarusian literature;

- communication breakdown in Belarusian-Ukrainian literary ties.

Map of meanings

Minsk

In our reviews, which we have been conducting for more than a year, identifying new trends in the Belarusian literary process, we try not to repeat ourselves. But we have one sad tendency, about which we cannot be silent. Repression against cultural figures in Belarus has not stopped in the past three months. According to monitoring of violations of cultural rights, which is carried out by the Belarusian PEN, “as of July 1, 2023, at least 133 cultural figures, 114 of whom are recognized as political prisoners, are under criminal prosecution in colonies, prisons, pre-trial detention centres, open-type institutions or in “home chemistry” [a kind of home detention].

Arrests and trials of creative persons took place; of writers, in July the poet and musician Mikita Najdzionaŭ, who was sentenced to 3 years of “home chemistry”, was recognized as a political prisoner.

On parole in Belarus, the cultural situation remains consistently stifling. Creators and facilitators of the literary process still connected to the state exist in the “mouse under the broom” regime. The concepts of “raids” and “purges” have become a permanent fixture in the lexicon of civil servants. Power structures, clearly not having enough human resources for close control, organize wild hunts for these mice. All the time to expect (to finally have them) checks, dismissals, arrests, imprisonments – this is the atmosphere in which the book business in the country is, as close as possible, to the atmosphere of the USSR or Germany in the 1930s.

Wolf tickets and blacklists operate almost without interruptions: it is forbidden to employ culture specialists who have been fired for political reasons in Belarus. Even for a role of a conventional boiler room attendant. As they say, everyone’s dismissed – we’re not going to see a new generation of “janitors and watchmen”. Self-censorship is rampant: out of trouble, museums, bookstores, and libraries try not to hold or present anything that contains the words “freedom,” “peace,” “Ukraine” and other triggers for propagandists.

Large-scale purges in literary circles, dependent on state resources, have not yet been observed. Maybe it’s just a matter of time. It’s a sad intrigue: is the field of literature left for dessert, or will it not be touched at all as a non-mass, insignificant phenomenon today? In any case, you can’t envy Aleś Karlukievič and Badak, as well as Viktar Šnip – the satraps of the official literary process. With this rate of marginalization of the creative and intellectual stratum, very soon they will have to write or at least sign everything that is issued at the expense of the state.

Minsk

Within the scope of our extremely concise review, we consciously do not review Belarusian book novelties (which appear both internally and externally in a ratio of approximately 2:1, still in favour of internally) and we do not even consider it obligatory to report on their appearance, but as an exception let’s pitch the idea for analytics to a group of colleagues. In May 2023, the book “Adventures of Pranciš Vyrvič, Marshal of Minsk” was published – the seventh, final part of Rubleŭskaja’s historical adventure saga, which she has been creating since 2018. It would be interesting to analyze whether, as we think, this project really combined Uładzimir Karatkievič’s life hacks in reformatting and popularizing national literature with the humanist and educational ideals of Joanne Rowling. How similar is Pranciš Vyrvič to Harry Potter?

Guangzhou

So far, the review of new Belarusian books is boring. As an example, we can cite the conversation of Radio Svaboda with a literary reviewer under the pseudonym (?) Viera Biejka on July 16. 2 (two) reviews written by a new author for the online magazine “Taŭbin” became a newsbreak. As they say, intellectual hunger detected.

The conversation with a critic who works at a university in China was successful, because it makes you want to disagree with something, inserting your five kopecks / euro cents / groshy / whatever you call a change from yuan or lari. Dear Viera Biejka answers the question why Belarusian books are not reviewed today:

“Approving what you subjectively like, condemning what you subjectively do not like – this is a difficult legacy of Soviet criticism, and the current young critics and critics, I’m afraid, do not even realize that they are the descendants of the Soviet version and the Soviet understanding of the role of a literary critic. Sooner or later, such criticism, which serves someone’s tastes or some kind of friendly community, inevitably fails, because the reader is not a fool, and, of course, sees bias and non-literary goals”.

The author noticeably hides her face, although she allows her identity to be calculated based on the details of her biography. Nevertheless, by agreeing to talk to the “extremist” medium, she almost does not touch on the political factors of the decline of Belarusian professional criticism. Allow me to introduce a little primitive Marxism. Since 2020, the Ministry of Information has been consistently and methodically destroying the “basis”. All media and cultural platforms, on which meaningful reviews appeared in 2019, are blocked or censored. They appeared mainly thanks to the sympathy of editors, despite the general reader’s lack of demand for professional book reviews and, as a result, their catastrophic lack of clicks. It is worth mentioning at least the literary analysis of one author for the late TUT.by or the five-book sets of one author for the still alive Onliner… What now? What new or relocated media / culture portals (besides “Taŭbin” and “Litradio”) consistently and purposefully provide space for qualified reviews? Are there any announcements of book novelties, conversations with authors, historical and local history essays about classics, reprints from foreign media?… The question hangs in the air.

So the opinion about the decline of criticism due to some ideological factor is perceived as one-sided. A rejection of Sovietness in itself is nothing more than a post-Soviet (post-colonial) syndrome, when everyone is afraid of being accused of Soviet relics. Because, it seems, “approve what one subjectively likes, condemn what one subjectively does not like,” is exactly the professional duty of a reviewer: gaining objectivity, criticism drifts into literary studies. So what is subjectivity in criticism? If a competent critic subjectively does not like the right-wing views reflected in the work, then it is left-wing or liberal criticism; if patriarchal views are not supported by a critic, then it’s feminist criticism. Discrepancy of the ideological content of the work with the postulates of the Gospel will be banished by Christian criticism and so on.

Unfortunately, in the history of our literature, punitive criticism also happened, when the debacle in the press was preceded by the expulsion, execution or placement of writers in an insane asylum. All the above, and not as formulated by Viera Biejka, we consider Sovietism in criticism, alarming: its time is returning. And it is embodied not by some abstract “young critics”, but by quite concrete mature propagandists.

Viera Biejka, according to the introduction to one of the reviews, subjectively does not like categoricalness in the reviewer’s craft. Apparently, before us is a kind of academic criticism. Clicks will show whether the reader will like it 🙂

But we want to agree with the opinion of the literary reviewer about the danger of commercialization of criticism and its “money subjectivity”, perceiving it as an impulse to share an observation. Amidst the decline of professional critical longreads, book blogging is flourishing in the Belarusian segment of Instagram. Juicy mini-reviews, often in the format of memes, videos in stories and reels, have an image – the cover of the book – as a trigger. And authors often consider an opportunity to buy it in bookstores a a reason for writing a review on it.

Whether such a trend is for the good is an open question, just worthy of discussion.

Although it is impossible not to mention the educational intentions of instabloggers @pakrysie and @kniznyja_razmovy (the first account can be called Belarusian-centric, the second – literature-centric).

Online

Regarding Internet portals. In July, a new (or a well-forgotten old one) website was launched – bellit.info: everything about Belarusian literature. The resource identified itself as a project of the International Union of Belarusian Writers – NGO founded in 2022 in Lithuania on the initiative of the Belarusian-Swedish writer Dźmitryj Płaks for the purpose of “uniting and consolidating literary forces”. Digitizing, for example, the archive of personal files of the BSSR Writers Union, the portal demonstrates continuity with the independent Union of Belarusian Writers, whose existence was terminated by the regime in 2021, and testifies to the relocation of one of the largest literary organizations from Belarus (at least partially). For now, human rights and journalistic content is dominating on the portal, but perhaps the quantity of literary and critical material will increase over time.

Meanwhile, the criminal authorities of the Republic of Belarus continue repression in the information space: in the past three months, the cultural portal “Budźma biełarusami!” (“Let’s be Belarusians!”) was recognized as extremist, and in order to use the free online library “Kamunikat”, residents of Belarus now need VPN services. According to Jarasłaŭ Ivaniuk, a Belarusian from Padliašša, who founded the portal in 2001, it “collects more than 50,000 Belarusian publications of absolutely different types”. An invaluable resource for students, historians, critics and literary scholars studying Belarusian literature, and teachers who teach it, it will continue to work, because, fortunately, it existed under Polish jurisdiction from the very beginning.

Kramatorsk

An alarming trend of late spring – mid-summer: deterioration, if not a complete break, of public Belarusian-Ukrainian cultural ties unilaterally. One of the first documents that confirmed Ukraine’s intention to end cooperation with Belarusians was the denunciation in the spring of 2022 by the government of Ukraine of all agreements with the Republic of Belarus in the field of education and science. The consequences are being felt this year: Ukrainian scientists who started research related to Belarus by 2022 are in an awkward position. It is almost impossible to publish their results today. Copyrights for printing Ukrainian books in Belarusian are not issued – even with the participation of publishers or teachers repressed in Belarus. Belarusian disputes between those who “left” and those who remained are leveled by the Ukrainian optics of the time of full-scale war. In the rhetoric of Ukrainian literary figures today, the narrative of collective guilt of people somehow related to Belarus prevails. Adherents of the opposite opinion prefer not to speak publicly to avoid embarrassment. At the beginning of July, at the request of Ukrainian women writers, Andrej Chadanovič removed Viktoryja Amielina’s poem he had translated, after she died in Kramatorsk. Earlier, in May, Aleś Płotka reported on Facebook about the refusal of the Ukrainian special services to let him into the country. Thus, any, even the most sympathetic acts of solidarity on the part of Belarusians are persecuted – and first of all, naive and passionate individuals suffer, such as the poet and translator Andrej Chadanovič, a long-time ambassador of Belarusian-Ukrainian literary friendship, and Aleś Płotka from Homieĺ – a poet, translator and promoter of Ukrainian culture, as well as a social activist who has been helping Ukrainians for many years.

What conclusions should be drawn from this, turning off emotions and turning on the ratio? Perhaps it is worth accepting this cooling situation in order to one day restart the ties between the countries in a new cultural and political situation, because for the last 30 years, with a few exceptions in the form of mutual translations or intense gatherings at literary festivals, they have just presented themselves as a “difficult Soviet legacy”. Uładzimir Karatkievič Street as a conscious choice of residents and city authorities, which appeared on the map of Kyiv in March at the initiative of the writer Viačasłaŭ Łevicki, – is much healthier than the “Minsk” station of the Kyiv metro or the “Kyiv” Minsk cinema as an exchange of compliments between “brother and sister” republics.

Nevertheless, the expansion of understanding among the Ukrainian establishment of the difference between the Belarusian regime and the Belarusian civil society, ideally supported by some normative acts (as it happens in most EU countries), is a good idea for the Belarusian democratic lobby, which will contribute to the restart of cultural ties.

London (read – the World)

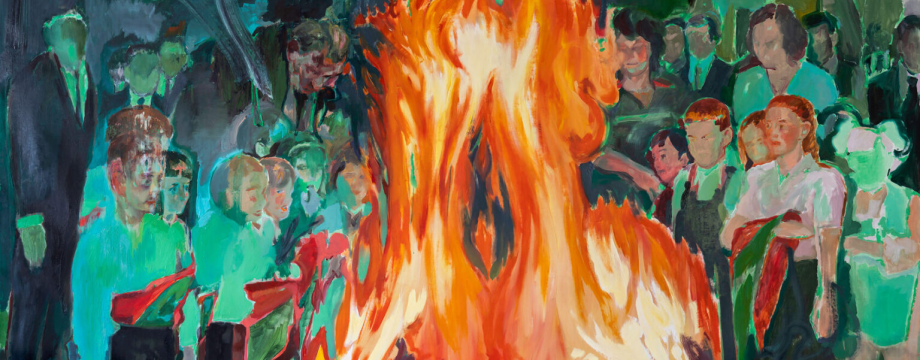

Summer impresses with the collaboration of mainstream Belarusian literature with the independent theatre scene. We are talking about performances based on actual works by writers who do not write for the theatre and do not belong to the theatre movement. The Warsaw performances of “the Kupałaŭcy” based on Bacharevič’s latest novels and the Vilnius performance of “Cichary” by Saša Filipienka were announced or sold out. Palina Dabravolskaja announced the restart of the play “Sarmatyja” based on the poem by Maryja Martysievič in a chamber format. But the grand event here is definitely a media rehearsal of the modern opera “The Wild Hunt of King Stach”, integrated with drama, which will be shown at London’s Barbican theatre in Belarusian with English subtitles in September (the author of the libretto based on the novel by Uładzimir Karatkievič is Andrej Chadanovič, the composer of the music is Volha Padhajskaja). The largest project in the history of Belarus Free Theatre is implemented by Natalla Kalada and Mikałaj Chalezin (in June, both were awarded the Order of the British Empire for their contribution to art).

Цізер оперы Беларускага Свабоднага тэатра паводле караткевічаўскага

“Дзікага палявання караля Стаха”

Responding to the sad trend noted above, Belarus Free Theatre involved a large number of managers and creators from Ukraine in the “Wild Hunt” troupe, because the main idea of the future play is “about the geopolitical knot of Belarus – Ukraine – Russia, which can be completely untied, otherwise imperial history will be endlessly reborn”. In addition, Mikałaj Chalezin calls the opera “an icebreaker that would ram big venues and bring small Belarusian projects with it, which could receive their dose of attention.” So the Great Silence of BelLit, the danger of which we stated a year ago in our reviews, is postponed for now.

Washington DC

And one more thing. The creator of the Skaryna Press publishing house, librarian Ihar Ivanoŭ, at the very end of the season reviewed here, published a working moment from the life of the US Library of Congress. Following Ukrainian literature, books from Belarus will be allocated this year in a section separate from the USSR/Russia (from DK507 to DK2001–2995). Which is called a “let’s just leave it here” act. After all, visitors to US libraries, especially university libraries, where the USSR/Russia study programmes have been seriously reduced over the last decade, had to see Belarusian books on the shelves labelled Asia.

Conclusions and predictions

- “Wild Hunt” is a metaphor for the season not only through the staging of Natalla Kalada and Mikałaj Chalezin. “Match-point”, in which the ball of repression froze, still endures. The suspense, in which the residents of Balotnyja jaliny were, is all too familiar to cultural figures in Belarus.

- Outside there is also a waiting, but less anxious. How will relations between literary Belarus and the world develop? Maksim Žbankoŭ’s forecast about three ways of development of domestic cinema –

- “going abroad and joining other people’s global (…) projects”;

- “going to virtual Belarus, creating a special (…) field in the global network”;

- the “most sacrificial, selfless and most senseless option: to continue nailing your niche (…) for a narrow circle (…). This means turning into a typical project of a cultural ghetto, endlessly ruminating on its injuries and problems. Most likely, all three options will be implemented – with an equally mysterious and unpredictable ending”;

- also works for a book business.

Belarusian cinema: in limbo

New trends for the season:

- exiled cinema increases distribution in diasporas and contact with viewers;

- cinema inside Belarus turns into ritual and simulation;

- apparently, there is a difficult transition to the reconstruction of reality, which is no longer possible to adequately record.

The last three months have been surprisingly fruitful. What is interesting, there have been events of a symbolic kind – which mean something important, but do not change the agenda. Maybe this is the current state of Belarusian cinema: we are stuck in the symbolic dimension. Yes, in limbo (the word “pamižža” was gratefully borrowed from this year’s exhibition of Belarusian photography in Lodz).

Between fantasy and parody

Let’s start with the encouraging thing: somewhere outside the borders of Belarus, the cinema created events quite enthusiastically. Mostly small ones, according to their emigrant-suspended position.

But there were also Vilnius screenings of the “Unfiltered Cinema” film festival that was cancelled in Belarus, Warsaw screenings of Belarusian films, and the documentary film “Motherland” at the Krakow Film Festival (with the reception of the elegant prize of audience sympathy, and the prize for the film “Na żyvo” by Mara Tamkovič at the Freedom Film Festival in Radom.

In the meantime, by the way, the filming of Ms. Mara’s feature film “Eight Years and Three Months” was completed. The film, discarding the exact mentioning of Kaciaryna Andrejeva’s term of imprisonment, got an abstract and romanticized name – “Country under a grey sky”. For now, we will refrain from conclusions.

A documentary artist Maksim Švied showed his new film “Photographer from the Square of Changes” in the USA, and Nastaśsia Sierhijenia, known for the short feature film “Jay”, announced the premiere of the new film “You & I” at the end of August.

The premiere of Ivan Hapijenka’s animated film “Lullaby” and an exhibition of accompanying drawings took place as well. That Kafkaesque lullaby lulls our post-traumatic syndrome, deftly capturing its essence: hiding one kind of reality under another one. Additionally, those realities should externally coincide in their routineness – until the moment of the same routine trigger. If we are not mistaken, this is the first attempt to capture the current emotional state of Belarusians (and not only them) not through the interaction of witnesses and victims and not through the story as such. After a flood of narrative trauma films, the non-narrative, all-visual post-traumatic film seems like a metaphor for changing worldviews post-2022, not post-2020. Time has moved forward a little – that’s good already.

Meanwhile, somewhere in distant Spain, an inaudible premiere of the almanac “COOL (News from Belarus)” initiated by Mikita Łaŭrecki happened. Directors from different countries – and Belarusians too – made short films based on Belarusian news stories, which always turn out well into an absurd and even charming in its absurdity narrative. We do not have the opportunity to understand what kind of Belarus they will form together. Let’s hope that the story will go beyond the collection of anecdotes and show us the first fantasy about post-protest Belarus, which eludes representation and therefore can only be reconstructed in this way.

Closer to Belarus, in Poland, the parody duo The ČynČyns were distinguished by the short film “The ČynČyns flew over the cuckoo’s nest”, where the national collective Belarusian official with two heads – Siarhiej Mikałajevič and Mikałaj Siarhiejevič – revealed his origin. It’s very predictable and therefore distinctive. The charm and truth is that, moving from parody to trash and back, this doubled hero perfectly reflects the state and feelings of the modern Belarusian bureaucracy, stuck between parody, simulation and commitment of crimes. That through many parodic quotes from film classics, this film finally comes to the intonations of “The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari” – perhaps the most apt yet intuitive statement about the zeitgeist. Yeah, The ČynČyns easily, in a trash style, rhymed the dehumanizing and repressive emptiness of the current Belarus with the Germany of the early 1920s, in which German film expressionism arose. Thanks for that.

Between the Ministry of Culture and “Kupała”

By the way, as far as bureaucracy is concerned. It is doing well. It creates another expert council for the development of cinematography in Belarus, which is likely to develop what previous expert councils for the development of cinematography have not developed. Where did the previous ones go and why was there a need for a new one? It can only be explained by the self-replication of the Belarusian bureaucracy and its fractal structure.

Another predictable, but unexpected news is the replacement of the general director of the film studio “Belarusfilm”. The place of the capital functionary Uładzimir Karačeŭski was taken by the Hrodna functionary, the chairman of “Hrodnaablkinavideaprakat” Juryj Alaksiej. The most important thing in this news is the sign “Hrodnaablkinavideaprakat”, created, presumably, to impress the greatness of bureaucratic abbreviations.

The rest does not go beyond the old bureaucratic rituals that melted into the empty history of the film studio. To consolidate the ritual, empty tasks were set before the new general director:

- to expand the film studio’s cooperation with national television channels and the Belteleradiocompany,

- to form a professional team,

- to effectively implement the strategy of cultural import substitution in cinematography,

- to produce films demanded by the audience and aimed at patriotic education of the population.

And do you remember how, during the time of the pre-last head of “Belarusfilm” Ihar Poršnieŭ, we were amused by the task of turning the film studio into a factory, where plenty of Belarusian and foreign films will be shot? From those ambitious reconstruction plans to “find those who know how to shoot, and shoot at least something” – seven years and two ministers.

Let us remind you that the same Ihar Poršnieŭ, who was given ritual hopes for the revival of the unrevivable, received the following ritual task in 2015: “We live in Belarus, and our president once said: “When will you make a film that is understandable to the people, and at the same time it is interesting to watch?” I would like to fulfill my assignment: to shoot such a film, of course.”

The irony lies in the fact that during Poršnieŭ’s time, the green light was given to exactly this kind of film – understandable to the people. It turned out to be the “Kupała” project.

The next general director Uładzimir Karačeŭski carried the “Kupała” like a flag: sometimes taking it out a little, sometimes hiding it – depending on the bureaucratic mood. And those movements turned out to be enough for a symbolic field of struggle to form around the film and a separate legend with the traditional Soviet triangle of author – viewer – censorship machine (see – the model still works).

Now we are watching how “Kupała” independently becomes a measure by which we can count the stages of our dim existence: “between the first and second presentation of “Kupała” on the Internet”, or “when “Kupała” was posted, but asked not to watch”, or “between the second and third presentation of “Kupała” on the web”, etc.

Finally, the final version of “Kupała” was posted on the Internet, and on the eve of the anniversary of the elections, diasporas in Poland, Georgia, and the United States organized sessions. We believe that the life of the film will not end there, because it is symbolically superimposed on the relationship between the authorities and the people. And a very imprecise, but obvious and, most importantly, visual parallel with the events of 2020 in the plot works. That is, the situation created in 2020 has not yet been resolved.

It seems that after 20 years, Uładzimir Jankoŭski finally directed his “Anastasija Słuckaja”, which he abandoned in 2003, in the form of “Kupała”: a film created so that it would be “understandable to the people”, through which the authorities speak to the people about a certain unity. It’s just that everything finally turned out “not so clear” with the authorities as expected.

Between the old and the new

Meanwhile, “Belarusfilm” strained itself and published a stack of news.

First of all, the “good and cosy” film by Alaksandr Jafremaŭ “Letter of Waiting” was quietly released in a modest symbolic distribution. – it’s about cardiologists who stay true to their profession. And this loyalty, of course, is identified with loyalty to the motherland and the state. Which, moreover, identify with each other (yes, you correctly grasped the metaphorical thread of the current bureaucratic cinema: heart – homeland – state). It is difficult to find fundamental differences in it from his own film “Rhymes with Love” (2006) – one thing is that there were hematologists who were not yet so concerned about love for the homeland, perhaps due to specialization: the homeland is in the heart, not in the blood.

Secondly, the young directors-animators of “Belarusfilm” debuted in May with the almanac “New Year’s Kaleidoscope”.

The news is notable not only for its unimaginable timeliness, but also for the fact that we learned about the existence of young directors at the animation film studio (we haven’t heard anything about this since almost 2017). Let’s write down the names: Julija Pincak, Vital Andrasiuk, Daniił Žuhžda i Jana Arystava-Halinoŭskaja. We will check the list in a year.

Thirdly, a graduate of the Academy of Arts, Kirył Chalecki – perhaps the only member of the weird youth film studio Smolk@ at “Belarusfilm” – started filming the debut full-length film “Kinoshniki”.

“We actually show how a debutant director goes through the various stages of creating his film”, – Mr. Chalecki is quoted by the Ministry of Culture.

While there is no opportunity to get acquainted with the film itself, we simply observe how Mr. Chalecki voluntarily or involuntarily serves a cannibalistic bureaucratic situation, when a direct professional duty – to support and introduce new generations into the workshop – is passed off as a privilege and demands loyalty, and the demonstrative support of individual newcomers decorates the old system generational conflict and the prevention of new personnel in the industry, which is also purged.

We still remember that the previous almanac of young filmmakers “This is me, Minsk”, started in 2019, has not yet been released, in which, by the way, Minsk is also built on the metaphor of cinematography, and those pictures capture not too normative, but sometimes a painfully corrosive image of an empty city and empty time.

What do you think: which of these two films will be released first?

From chronicle to simulation

It is difficult to comment on the unexpected and optional, sloppy and late film about the protests “Chronicle of Modern Times”. One thing is that irony reigns here. The film, which has possibly become the reason for repression, itself is very similar to operational shooting: no interaction with the characters, deepening into the crowd, highlighting moods, collisions or characters.

We say “possibly” only to indicate the fundamental situation: we no longer have access to reality whether we’re staying in Belarus or abroad. And we can guess about it basing our judgement only on those fragments of constructed images that the security forces, propaganda and sometimes other media give us. And the criteria of their truth and adequacy have already been lost.

We can imagine and be afraid, play it safe or ignore caution, as the director of “Chronicle” did, but we are no longer able to say how it really is: every offered fragment tells us the truth and lies at the same time.

Maybe that’s why the protests filmed by their participants became the last documentary reality available to us. And the last effective way to contact it is through streaming a video. After that came the “repentant” videos, a genre of dual simulation, “which does not exist, but does exist.” And now it is impossible and dangerous to fix that reality, disfigured by simulation. It is only possible to reconstruct. “Chronicle of Modern Times” marked this important division, which we, while noticing, did not pronounce. But, we suppose, lots of people would choose to do without such untimely luxury.

Meanwhile we may note that the format identified with Belarusian solidarity and unity is still the stream: the marathon “We do care” symbolically showed it once again.

In short, it seems that the pitfalls of Belarusian cinema – the threat of turning it into a bureaucratic ritual, then into the exploitation of protest unity – have been ignored so far in order to take a breather.

The autumn festival routine awaits us: “Northern Lights” and “Bulbamovie” festivals have already announced the acceptance of applications. “Listapad” should launch soon. But the inner emptiness will not disappear. And it demands decisions that are unlikely to be made. In this light, an informal congress of independent Belarusian cinematographers on August 18-20 in Warsaw may seem like an attempt. But even that still does not avoid the threat of turning either into a ritual or into exploitation. And we are waiting and watching.

Theatre: survival in Belarus, temporary renaissance abroad

The main trends of the season:

- dismissals and repressions continue in the Belarusian theatre, further changes in the repertoire are announced – the purge of the theatre territory from the pre-revolutionary heritage is gradually approaching its completion;

- they announced the time of transition to a new financing system, under which state theatres will receive even less assistance from the state;

- in the international dimension, the domestic theatre is increasingly turning into a platform for showing the productions of Russian theatre groups;

- thanks to the new production initiative INEXKULT, the Belarusian theatre abroad demonstrated that it has a chance to overcome management and financing problems;

- Polish shows of INEXKULT finally established the priority of this country in the Belarusian theatrical emigration.

More layoffs and transition to a new financing system

Repressions and dismissals in the Belarusian theatre industry do not stop. Now the time has come for the Belarusian State Puppet Theatre – until recently it remained the last major collective in the capital, which was almost untouched by the new state policy.

In past reviews, the departure of the director Jaŭhien Klimakoŭ and an actress Sviatłana Cimochina was mentioned (in the first case, at least it was formally voluntary). Now they did not extend the contract of the main director Alaksiej Lalaŭski – without exaggeration, a great Belarusian creator who has worked in his position since 1986.

Formally, he has not staged new plays for the past two years. But the very fact of his taking the position was a manifestation of tradition, respect for the past and creative continuity – all this is disappearing from the Belarusian theatre space with catastrophic speed. Therefore, the dismissal of Lalaŭski looks like an approach to the final “turning of the page” and an almost complete purge of the theatre territory from the past pre-revolutionary heritage (we are talking about the events until 2020). Obviously, no one is going to stop repressions.

At the end of July, the Ministry of Culture held a meeting with the participation of the management of most theatres. One of the heads of the Ministry of Culture, Iryna Dryha, stated, that from January 1, 2024, state collectives will switch to a combined financing system, in which only part of the expenses are covered from the budget.

The new model has been talked about for a long time. In February 2021, Alaksandr Łukašenka formulated it in the following way: “You earned two million dollars – two million dollars will be added from the budget. You earned five – five will be added.” In August 2022, the transition to a new scheme was announced by the Prime Minister Raman Hałoŭčanka.

In 2017–2019, the share of off-budget funds in large republican theatres reached 34%. In the regions – the figure was up to 37%. But such numbers were achieved by strict implementation of the plan, the need to show a large number of entertainment products, which prevented the development of the collective and actors.

Dryha’s words are the first to announce specific dates for the transition to such a model. Although there are no specific numbers yet.

In the note about the meeting with the official, it was mentioned about the need for “significant updating of the repertoire with the aim of staging performances that ensure increased demand from the audience.” Theatres are now allegedly interested in plays about “modern heroes of Belarus, the Great Patriotic War, the problems of the young generation these days, and the glorious past of Belarus.” Authors are advised not to be afraid to “touch on the acute social topics of our time, the correct political attitude of the author is essential. The patriotic educational beginning is welcomed, though not “head on”, but on positive examples of the activities of the characters.”

Formulas of happiness

Officials thus kill two birds with one stone.

Firstly, they incentivize theatres to earn more to fulfill the mandate from above. As a result, this will lead to the production of even more entertaining / classic / plot-tested, etc. performances, which will put a cross on any experiment.

Secondly, in this way they plan to get rid of “old” authors in favour of “new” and “patriotic” ones. However, the news itself – even its title “High-quality domestic plays and librettos are urgently required!” – indicates that, perhaps, such works still need to be written. The expression “plays staged by peripheral and even independent groups can arouse interest in large state theatres” is alarming. Supposedly, the collectives should expect an invasion of hitherto unrecognized creators with material of the corresponding level.

The solution in such a case is to turn to the classics (or even to their less well-known works). For example, the Republican Theatre of Belarusian Drama turned to Uładzimir Karatkievič’s short story “Karniej – the death of a mouse”, dedicated to the Second World War. In order to create a full-fledged play based on it (director – Alena Zmicier), excerpts from the writer’s prose, his poems and essays were added to the staging.

Personnel hunger – a consequence of repression – is still felt in the domestic directing industry. Among the directors of the capital, the work of Jaŭhien Karniah, who produced the play “Smart dog Sonia” in the puppet theatre, remains a reminder of the past. That is why “career elevators”, characteristic of the society of the time of repression, inevitably start to work: those who have accepted the rules of the game (or who are lucky) quickly jump through several steps.

For example, the director of the Paleski Theatre (in Pinsk) Pavieł Marynič, who has never had experience working in large theatres and has so far staged only in his own team, was invited to the production of the play “The Tale of the Dead Princess” at the state Kupała Theatre.

In the international aspect, the Belarusian theatre is increasingly turning into a platform for Russian groups. Troupes from Russia took part in the capital’s “Ballet Summer” forum, visited “Theatrical meetings” at the “Slavic Bazaar in Viciebsk”, came on tour to the Minsk Theatre of the Young Spectator. They do not plan to stop such a policy: the Kazan Theatre shows are announced for the fall at the state Kupała Theatre.

INEXKULT: Belarusians in Europe

In previous reviews, the difficulties faced by the Belarusian theatre abroad were discussed. Including the interrelated problems of management and financing, which led to the minimum number of performances.

In the summer of 2023, the situation changed dramatically thanks to the new production initiative INEXKULT, which launched the theatre festival INEX FEST. Thanks to it, a number of domestic productions were shown in Warsaw. These are two plays by the director Palina Dabravoĺskaja – “Sarmatyja” and “I will come out of the forest, I will pull out my spine, and it will serve me instead of a sword”. Productions “Unemployed tree” (director – Sviatłana Bień), “Mama Zoja, Bielaruś” (Belarusian-Swedish project, director – Aksana Hajko together with the performance ensemble) and “rEvolution of the Hare” (director – Jura Dzivakoŭ). And also several performances of “the Kupałaŭcy”: “Whisper” (director – Raman Padalaka), “Geese-people-swans” (director – Alaksandr Harcujeŭ) and “Judzif Comedy” (director – Pavieł Pasini).

The festival helped draw attention to Belarusian theatre, as well as prepare the premieres of “The end of the half-boar” (work by Jura Dzivakoŭ) and “Victory Square” (work by Alaksandr Harcujeŭ). It was also possible to expand the geography of the shows. For example, in addition to Warsaw, “Whisper” was seen in Krakow, Sopot and Vilnius.

Geography of the INEX FEST shows, which, for the sake of objectivity, was initially conceived as Warsawian, finally secured Poland the first place and unconditional priority among the Belarusian cultural emigration. There are many reasons: the similarity of the Polish and Belarusian languages, which helps adaptation; higher standard of living in this country compared to Lithuania; issues with the legalization of a part of the creators are still relevant (it is those issues which make it impossible for them to go abroad, and therefore to tour).

But the contrast is obvious. Let’s add that, in addition to the forum in Poland, there were also regular premieres. For example, “Chryścina’s Sea” (director – Andrej Novik), which was released in June by Team Theatre (the play is dedicated to the events of August 9-14 in Belarusian police stations). Against the background of many Polish performances, only one premiere took place in Vilnius during this time. We are talking about “Cichary” (by a Ukrainian director Saša Denisava). More precisely, they were announced as a reading, but looked like a full-fledged, ironic and stylish performance, one of the best about the events of 2020. In other countries, numbered productions are generally shown (such as the “Batlejka Šahał” project by Alaksandr Ždanovič in Tbilisi).

It is worth mentioning the personal successes of domestic artists. An opera singer Illa Silčukoŭ made his debut in Dvořák’s “Mermaid” at the famous Milanese theatre La Scala. It is already known that from the 2024/2025 season Vital Aleksiajonak from Belarus will become the chief conductor of the German Opera on the Rhine. Natalla Lavanava directed the performance “All hope in an egg” at the Poznań Theatre of Animation. And Palina Dabravolskaja staged “Heroines” at the Husa na provázku theater in Brno (Czech Republic). This gives the mentioned creators the opportunity to further develop and build a career in European theaters.

Conclusions

The pressure from the authorities on the domestic theatre does not stop. Dismissals and purge of collectives from the remnants of the former freedom of the past decade continue. In the international aspect, the Belarusian theatre becomes a platform for Russian theatre groups. For individual creators, these circumstances become an unexpected career opportunity. In general, the Belarusian theatre in the country survives and tries to adapt to new conditions without losing itself.

Belarusian theatre abroad experienced an unexpected renaissance, connected with the new production initiative INEXKULT. In the future, it will be clear whether this revival is permanent or temporary. Rather, the latter, because in any case, the problems that existed until now (lack of support from institutions, the need to work somewhere other than theatres, etc.), have not disappeared. One can only hope that the new initiative, if it continues, will help to resolve some of them.

Pop & Rock: summer game simulating the presence of the market

The main trends of the season:

- the festival summer in Belarus and abroad measures the creative potential of musicians and the tastes of the audience;

- the specificity of the activity of Belarusian musicians: new material is almost not created abroad, new names appear in the country;

- independent media: ignoring musical (and cultural in general) topics and lack of expertise.

Festivals: ideology and commerce

The festival summer is an excellent indicator by which many processes in Belarusian music can be measured – even in the circumstances in which the sphere now found itself. This is the cataloging of assets, the fixation of narratives, the evaluation of creative potential – the festival industry (or at least a faint hint of the industry) demonstrates the tastes of the audience and the ability of cultural managers to satisfy them.

All existing Belarusian festivals can be divided into two conditional categories: commercial and ideological. This will allow us to understand both the tastes of the mass audience and the narratives of propaganda and counter-propaganda.

Music festivals within Belarus have shrunk to the necessary and permitted minimum. Even the Vulitsa Ezha festival in the Botanic Garden, which is the most herbivorous in its choice of artists, abandoned the musical programme this year and finally turned into a feast of gastronomic hedonism.

An interesting nuance: the state completely took over not only administrative control over music imports, but also all business processes. In order to bring a foreign artist to Belarus, it is necessary to somehow agree with the state institutions so that they will take over the legal reporting and act as the official organizer of the event. Even large concert agencies, which still survive in the most restricted space, are forced to work through state institutions. For example, the concerts of the Ukrainian-Russian singer Anna Asti, which were recently held by the Atom entertainment agency, are now organized by the Palace of the Republic.

It is the same with festivals: if the organizer wants to bring a foreigner to Belarus, (s)he must seek contacts with state institutions. It’s a new level of dissent filtering and a new way to put your money where you want it.

As a result, only two local festivals with a local line-up remained in Belarus: “The Feast of the Sun” (“Свята сонца”) і “Our Hrunvaĺd” (“Наш Грунвальд”) (although they did not happen without certain problems in the formation of the musical part). Plus there was a handful of international festivals, each of which has its own development paradigm.

“Slavic bazaar” (“Славянскі базар”) almost every year claims to be almost on the commercial rails, but something keeps getting in the way. In principle, the reasons are clear to everyone except the organizers themselves: the audience of pop artists from television is rapidly shrinking together with the audience of television itself. And the musical component of the festival remains unchanged from year to year. Here you can again see the concert of all the stars of “Chanson-TV” and the solemn exhumation of pop trash from the past. It is a completely ideological product that works on the basis of loyalty and dedication to the principles of existence in conditions of non-freedom. A roll call of creative outsiders, a ball of artificial songs performed by mercenaries of totalitarian ideology.

On the other hand, another Viva Braslav took place in Belarus this year – the largest commercial festival that exists according to the principles of the market in the absence of it. About 30,000 people attended the event in the resort area this summer, and this is a good indicator of the tastes of the mass audience. The line-up of the festival is a celebration of commercial pop music, attended by popular Western DJs (and this is already a sensation for current Belarus), as well as current and not so pop singers from Russia (Artik & Asti, Hammali & Navali, “Otpetye moshenniki”/“Отпетые мошенники”, “Band’eros”/“Банд’эрос”) and Belarusian artists (Bakiej/Бакей, Prosta Lera/Проста Лера, saypink!). This is the only successful attempt to make Belarusian open-air popular. But there is also a nuance here: stylistically and geographically, the musical component of Viva Braslav has hardly changed since 2019. It exists in parallel with ideological narratives and is their subconscious reflection.

Our foreign festivals take place according to a different logic and in the absence of commercial partners and sponsors. Initially, this is a quest to find money. Then – a challenge in forming a line-up taking into account financial possibilities. And then it’s an attempt to break into the information space, oversaturated with political content and other people’s narratives, and it serves Belarusian cultural topics in spare time.

This year, three festivals took place in Poland abroad, which were different in terms of content, format and conditions: Varušniak, based almost entirely on the DJ line-up, Hučna Fest, more traditional according to the musical component, and the successor of the cult “Basovišča” – the Tutaka festival.

All three festivals were held under conditions of limited funding and lack of commercial partners. Therefore, the line-up was formed taking into account the possibilities of the organizers and their general idea about the musical tastes of Belarusians abroad. Each of these festivals is far from selling out the aforementioned “Basovišča”. But each of the events individually and all of them together can be considered a good attempt to mark the presence of Belarus in the expatriate life of Poland and the formation of a full-fledged diaspora.

Creative pits and creative hunger

The period of summer festivals is usually a demonstration of fresh material from creators: testing a new programme, a good newsfeed to stir up an inert listener. At least this is how the pragmatic coordinate system of world popular music works.

Belarusian music does not live according to these rules: it either completely ignores them, or it does not see the need to exist in this system of coordinates. One way or another, Belarusian musicians who took part in festivals in Belarus and abroad this year did not prepare new programmes. The tour continues with the old material, which invariably evokes a feeling of déjà vu. Popular Belarusian bands and performers live in a state of creative hunger.

The émigré scene continues to exist in touring mode and keeps the audience entertained with old hits: so far it works, but obviously not for long. Outside the borders of Belarus, artists compete not only with each other, but also with many world stars. And this competition can be sustained only thanks to an interesting and unique offer.

But there are also pleasant exceptions. It is worth noting the Berlin project KOOB of a Belarusian singer Lera Dele – it’s modern, charismatic jazz, which pulsates with energy and love for music. Belarus lacks such music – on the border between experiment and tradition, liberated and professional, authentic and multicultural.

Or let’s take the eclectic noir of Sick Mirror: thick blues mixed with psychedelia and sometimes even stoner. It’s an interesting and diverse album, which combines a lot of dark shades. It was invented and recorded by excellent musicians with good taste and interesting thinking: standard turns into non-standard and clear becomes mysterious.

It is also worth paying attention to the Homieĺ metal with stadium potential – Torf. This is music for large venues and festivals, explosive and melodic, works according to clear pop canons – and this is its main advantage. We have a massive quality product with trendy sound, bright melodies, catchy riffs and great visuals.

Another interesting project is lifo. Musicians exploit not the most obvious original sources. The album Atoire Sakidashi, Vol. 1 has both the noisy pulsations and guitars characteristic of My Bloody Valentine, as well as the gentler formulas used by Slowdive: working with a melody around which the sound of the composition is built.

It is interesting that almost all these albums (except KOOB) were recorded and released on the territory of Belarus. Even in conditions of ultra-censorship, musicians in the country show much more creative energy than the emigrant scene.

Independent Belarusian media: ignoring cultural topics and lack of expertise

The problem of the Belarusian freshman is the lack of interest on the part of information resources. Attention is paid to completely different characters and events. First you are a political prisoner, and only then a famous artist. In these circumstances, it is impossible to hope for at least minimal attention from the independent Belarusian media. The creators must look for other means of communication with their listeners, and the listeners – other channels of information.

And here there are two main points. The first is that independent media unconsciously serve the interests of propaganda. Its ambassadors and bearers are a priority in the information space, every expression of a conventional celebrity becomes an occasion for publication. Trash content instead of education, clickbait as a religion – trying to be a tabloid in the absence of a market looks like trying to try on Turkish jeans on a cardboard box in the rain. The second point is the lack of expertise. Belarusian independent publications exist in a state of absence of significant budgets. In this format, it is impossible to be a trendsetter: you only relay other people’s meanings and narratives. To maintain a cultural expertise in such circumstances is an unreasonable luxury. And this in turn leads to twisted logic like “this content is not interesting to our readers”. As a result, the majority of Belarusian independent media lacks information and analytics about the cultural field. Instead, the whole meager propaganda treasure, regular shock content for impressionable editors, is beautifully presented.

The result is a frantic race for traffic in the absence of a market, the dubbing of other people’s narratives and the complete absence of a comprehensive strategy for creating Belarusian content. It’s counter-propaganda without an ideological foundation.

Conclusions

The only commercial Belarusian festival on the territory of the country and abroad illustrated the real interests of the mass public: Belarus is getting deeper into the Russian context and has no other options yet.

Belarusian festivals abroad take place under conditions of minimal budgets and offer a modest local line-up.

The artist in exile has not yet offered the public a new programme. In the near future, this will lead to a decline in interest on the part of the Belarusian public. On the other hand, new names appear within the borders of Belarus, even under conditions of ultra-censorship.

Belarusian music is almost completely deprived of informational support from independent media. The focus is on nonsensical state propaganda, and the creator becomes a newsmaker only in extraordinary circumstances.

The Art: Inside and Beyond the Borders

The Main Trends of the Season

- Death of Aleś Puškin (1965 – 2023): While politically motivated persecutions and the eradication of resistance persist, the challenges faced by artists within Belarus are alarming. The tragic death of Aleś Puškin while incarcerated stands as a harrowing example of the grave threats and immense pressures that artists confront in the nation.

- Geographical Disparity Persists: A clear division has become evident between artists who chose to remain in Belarus and those who sought opportunities abroad.

- Initiatives, Collaborations, and Art Activism Abroad: Belarusian artists situated outside the country aren’t just focusing on their craft. They actively collaborate on international platforms and voice their opposition to conflicts, notably the war in Ukraine.

- Fostering Community Engagement: A growing trend in the cultural landscape is the organization of conferences and initiatives like “Imagining OpenMuzej Belarus,” which foster discussions and collaborations among artists, curators, researchers, and activists.

- Revitalization of Domestic Art Scene: Despite the overarching political and societal pressure, Belarus remains a hub of artistic activity. The art scene is experiencing a resurgence with a notable increase in both individual and group exhibitions, a majority of which steer clear of political content.

Death of Aleś Puškin (1965 – 2023)

On July 11, the tragic death of Belarusian visual artist, activist, and political prisoner Aleś Puškin sent shockwaves through Belarusian civil society. Found unconscious with severe medical conditions in jail in Hrodna, he died after surgery, leaving behind a community in mourning and a legacy of courageous opposition to oppression. His five-year sentence in a strict regime colony for his anti-Bolshevik art and vocal resistance against the regime encapsulates a life committed to freedom of expression and human rights. The news of Puškin’s death, and the terrible details of alleged medical negligence, stirred a profound sense of loss and outrage. In response to this unbearable loss, the Belarusian Council for Culture organized a memorial campaign to support his family and preserve his inspiring and invaluable creative heritage. Aleś Puškin’s story is a painful reminder of the sacrifices made in the pursuit of artistic freedom and human dignity. The echoes of his voice and the vivid imagery of his art remain as lasting tributes to a man who dared to speak truth to power and paid the ultimate price.

Initiatives, Collaborations, and Art Activism Abroad

Belarusian artists situated outside the country aren’t just focusing on their craft. They actively collaborate on international platforms and voice their opposition to wider regional conflicts, notably the war in Ukraine. This has led to a series of art events and exhibitions, both poignant and evocative, that explore not just the emotional landscapes of war but also the complex interplay of identity, politics, and history.

On May 4–5, the International Coalition of Cultural Workers in Solidarity with Ukraine at Karlsruhe, Germany, showcased 15 video works and 24 slogans concerning the ongoing war in Ukraine. This was a concerted effort by this curatorial collective and ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe to emphasize that the war’s impact is a shared tragedy that casts a shadow over the 21st century. Belarusian artists who contributed to this event include Bergamot Collective, Hanna Školnikava, Vola Sasnoŭskaja & a.z.h., Lena Davidovič, Žanna Hładko, Nadzia Sajapina, Andrej Durejka, Lesia Pčołka, Antanina Sciebur, Alaksandr Kamaroŭ, Maksim Tymińko and Siarhiej Šabochin.

On June 18, the closing of “If Disrupted, it Becomes Tangible” exhibition took place at the National Gallery of Art. Vilnius, Lithuania, continuing the theme of political unrest and conflicts. Curated by Alaksiej Barysionak and Antanina Sciebur, this exhibition delved into politics, technological influence, and mixed historical narratives, featuring works by the eeefff Belarusian art collective and Uładzimir Hramovič among the international cast of artists.

Two solo exhibitions, “Eternal Flame,” by Andrej Arno hosted by the Duży Pokój Gallery in Warsaw opening on May 11, and “Past Garden” by Raman Kaminski hosted by the HOS Gallery in Warsaw on May 18th reflect on the harsh reality of military conflicts, their connection with dictatorship and propaganda, and the impact on the trajectories of individual artists who find themselves in forced exile.

At the Free Belarus Museum in Warsaw, two exhibitions captured different facets of Belarusian life and identity. The “Close Borders” exhibition, which concluded on June 23, delved into the coexistence of seemingly contradictory identities such as LGBTQ+ individuality and conservative political views. Artists encouraged deep self-reflection and observation of diverse identities. Finally, to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the Free Belarus Museum, a new exhibition titled “Ad kraju da kraju” (From Edge to Edge) by Ihar Cišyn was inaugurated on July 22. Curated by Volha Mželskaja and reflecting the struggles faced by those in the affected regions, this installation echoed historical chronicles, political landscapes, and waves of Belarusian emigration. Through these exhibitions and collaborations, Belarusian artists have not only showcased their creativity but have also underscored the collective responsibility of art in voicing opposition, reflecting complex realities, and bridging gaps between history and the present day.

A growing trend in the cultural landscape is the organization of conferences and initiatives that stimulate dialogue and collaboration. On June 19-20, Ambasada Kultury hosted “Imagining OpenMuzej Belarus: community, contemporary art, engagement” at the Pilecky Institute in Berlin, Germany. Spearheaded by cultural leaders and art managers like Valancina Kisialova, Hanna Čystasierdava, Iryna Kandracienka, Siarhiej Šabochin, and Antanina Sciebur, this innovative initiative aimed to explore the possibilities of solidarity within the Belarusian cultural landscape. Through discussion panels like “Museum as a Structure that Embraces Community and Radiates Solidarity and Support” and “Solidarities, Horizontality, Community: Cultural Projects in Belarus,” the conference featured a rich diversity of voices, such as independent curator Alaksiej Barysionak, philosopher Volha Šparaha, artist Rufina Bazłova, and the eeefff group among others. Together, they emphasized the importance of community, solidarity, and connection in contemporary cultural practices, marking a significant step in fostering understanding and collaboration among the art workers in exile.

Revitalization of Domestic Art Scene

In Belarus, the revitalization of the domestic art scene is taking place against a backdrop of political turmoil. In May, a new museum dedicated to Belarusian “małyavanka” (traditional painted carpet) opened near Minsk as a branch of the historical and cultural museum “Zasłaŭl”. On June 17, the “A&V” gallery in Minsk hosted Andrej Pičuškin’s “Cartoons for Adults.” On June 29, the National Center of Contemporary Arts of the Republic of Belarus opened two exhibitions: “Beyond the Boundaries of Space” and “Symphony of the Great Cosmos.” A notable increase in both individual and group exhibitions is evident, yet they consciously steer clear of political content, a choice that warrants closer examination.

This tension is further illustrated by the July 8 update to the “Art-Belarus” gallery’s exhibition with pieces from the corporate collection of “Belgazprombank.” The collection’s seizure in 2020, connected to a criminal case involving money laundering and tax evasion, is a critical detail that doesn’t appear to have been sufficiently addressed by the gallery. Moreover, the value of the seized rarities was estimated at 20 million dollars, and its creation was thanks to Viktar Babaryka, a Belarusian banker and opposition political figure who’s been sentenced to 14 years in jail in 2021 and remains there to this day. This juxtaposition of cultural celebration with political oppression underscores the conflicting role art institutions play in modern Belarus and raise serious concerns about their ethical stance.

Summary & Predictions

- Continued International Influence: Expect to see an expansion of Belarusian artists’ influence abroad, with ongoing collaborations focusing on political and societal themes.

- Escalating Domestic Pressures: The challenges facing artists within Belarus are likely to persist or escalate, potentially resulting in more tragic incidents.

- Growing Community and Cultural Engagement: The trend towards fostering community engagement will likely gain momentum, building a more cohesive artistic community outside Belarus.

- Ethical Struggles within Domestic Art Institutions: Despite the seeming revitalization of the art scene, the complex ethical questions surrounding the avoidance of political content will continue to shape the cultural landscape of Belarus, with lasting impacts on how art engages with social challenges.

The Art: Inside and Beyond the Borders

The Main Trends of the Season

- Death of Aleś Puškin (1965 – 2023): While politically motivated persecutions and the eradication of resistance persist, the challenges faced by artists within Belarus are alarming. The tragic death of Aleś Puškin while incarcerated stands as a harrowing example of the grave threats and immense pressures that artists confront in the nation.

- Geographical Disparity Persists: A clear division has become evident between artists who chose to remain in Belarus and those who sought opportunities abroad.

- Initiatives, Collaborations, and Art Activism Abroad: Belarusian artists situated outside the country aren’t just focusing on their craft. They actively collaborate on international platforms and voice their opposition to conflicts, notably the war in Ukraine.

- Fostering Community Engagement: A growing trend in the cultural landscape is the organization of conferences and initiatives like “Imagining OpenMuzej Belarus,” which foster discussions and collaborations among artists, curators, researchers, and activists.

- Revitalization of Domestic Art Scene: Despite the overarching political and societal pressure, Belarus remains a hub of artistic activity. The art scene is experiencing a resurgence with a notable increase in both individual and group exhibitions, a majority of which steer clear of political content.

Death of Aleś Puškin (1965 – 2023)

On July 11, the tragic death of Belarusian visual artist, activist, and political prisoner Aleś Puškin sent shockwaves through Belarusian civil society. Found unconscious with severe medical conditions in jail in Hrodna, he died after surgery, leaving behind a community in mourning and a legacy of courageous opposition to oppression. His five-year sentence in a strict regime colony for his anti-Bolshevik art and vocal resistance against the regime encapsulates a life committed to freedom of expression and human rights. The news of Puškin’s death, and the terrible details of alleged medical negligence, stirred a profound sense of loss and outrage. In response to this unbearable loss, the Belarusian Council for Culture organized a memorial campaign to support his family and preserve his inspiring and invaluable creative heritage. Aleś Puškin’s story is a painful reminder of the sacrifices made in the pursuit of artistic freedom and human dignity. The echoes of his voice and the vivid imagery of his art remain as lasting tributes to a man who dared to speak truth to power and paid the ultimate price.

Initiatives, Collaborations, and Art Activism Abroad

Belarusian artists situated outside the country aren’t just focusing on their craft. They actively collaborate on international platforms and voice their opposition to wider regional conflicts, notably the war in Ukraine. This has led to a series of art events and exhibitions, both poignant and evocative, that explore not just the emotional landscapes of war but also the complex interplay of identity, politics, and history.

On May 4–5, the International Coalition of Cultural Workers in Solidarity with Ukraine at Karlsruhe, Germany, showcased 15 video works and 24 slogans concerning the ongoing war in Ukraine. This was a concerted effort by this curatorial collective and ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe to emphasize that the war’s impact is a shared tragedy that casts a shadow over the 21st century. Belarusian artists who contributed to this event include Bergamot Collective, Hanna Školnikava, Vola Sasnoŭskaja & a.z.h., Lena Davidovič, Žanna Hładko, Nadzia Sajapina, Andrej Durejka, Lesia Pčołka, Antanina Sciebur, Alaksandr Kamaroŭ, Maksim Tymińko and Siarhiej Šabochin.

On June 18, the closing of “If Disrupted, it Becomes Tangible” exhibition took place at the National Gallery of Art. Vilnius, Lithuania, continuing the theme of political unrest and conflicts. Curated by Alaksiej Barysionak and Antanina Sciebur, this exhibition delved into politics, technological influence, and mixed historical narratives, featuring works by the eeefff Belarusian art collective and Uładzimir Hramovič among the international cast of artists.

Two solo exhibitions, “Eternal Flame,” by Andrej Arno hosted by the Duży Pokój Gallery in Warsaw opening on May 11, and “Past Garden” by Raman Kaminski hosted by the HOS Gallery in Warsaw on May 18th reflect on the harsh reality of military conflicts, their connection with dictatorship and propaganda, and the impact on the trajectories of individual artists who find themselves in forced exile.

At the Free Belarus Museum in Warsaw, two exhibitions captured different facets of Belarusian life and identity. The “Close Borders” exhibition, which concluded on June 23, delved into the coexistence of seemingly contradictory identities such as LGBTQ+ individuality and conservative political views. Artists encouraged deep self-reflection and observation of diverse identities. Finally, to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the Free Belarus Museum, a new exhibition titled “Ad kraju da kraju” (From Edge to Edge) by Ihar Cišyn was inaugurated on July 22. Curated by Volha Mželskaja and reflecting the struggles faced by those in the affected regions, this installation echoed historical chronicles, political landscapes, and waves of Belarusian emigration. Through these exhibitions and collaborations, Belarusian artists have not only showcased their creativity but have also underscored the collective responsibility of art in voicing opposition, reflecting complex realities, and bridging gaps between history and the present day.

A growing trend in the cultural landscape is the organization of conferences and initiatives that stimulate dialogue and collaboration. On June 19-20, Ambasada Kultury hosted “Imagining OpenMuzej Belarus: community, contemporary art, engagement” at the Pilecky Institute in Berlin, Germany. Spearheaded by cultural leaders and art managers like Valancina Kisialova, Hanna Čystasierdava, Iryna Kandracienka, Siarhiej Šabochin, and Antanina Sciebur, this innovative initiative aimed to explore the possibilities of solidarity within the Belarusian cultural landscape. Through discussion panels like “Museum as a Structure that Embraces Community and Radiates Solidarity and Support” and “Solidarities, Horizontality, Community: Cultural Projects in Belarus,” the conference featured a rich diversity of voices, such as independent curator Alaksiej Barysionak, philosopher Volha Šparaha, artist Rufina Bazłova, and the eeefff group among others. Together, they emphasized the importance of community, solidarity, and connection in contemporary cultural practices, marking a significant step in fostering understanding and collaboration among the art workers in exile.

Revitalization of Domestic Art Scene

In Belarus, the revitalization of the domestic art scene is taking place against a backdrop of political turmoil. In May, a new museum dedicated to Belarusian “małyavanka” (traditional painted carpet) opened near Minsk as a branch of the historical and cultural museum “Zasłaŭl”. On June 17, the “A&V” gallery in Minsk hosted Andrej Pičuškin’s “Cartoons for Adults.” On June 29, the National Center of Contemporary Arts of the Republic of Belarus opened two exhibitions: “Beyond the Boundaries of Space” and “Symphony of the Great Cosmos.” A notable increase in both individual and group exhibitions is evident, yet they consciously steer clear of political content, a choice that warrants closer examination.

This tension is further illustrated by the July 8 update to the “Art-Belarus” gallery’s exhibition with pieces from the corporate collection of “Belgazprombank.” The collection’s seizure in 2020, connected to a criminal case involving money laundering and tax evasion, is a critical detail that doesn’t appear to have been sufficiently addressed by the gallery. Moreover, the value of the seized rarities was estimated at 20 million dollars, and its creation was thanks to Viktar Babaryka, a Belarusian banker and opposition political figure who’s been sentenced to 14 years in jail in 2021 and remains there to this day. This juxtaposition of cultural celebration with political oppression underscores the conflicting role art institutions play in modern Belarus and raise serious concerns about their ethical stance.

Summary & Predictions

- Continued International Influence: Expect to see an expansion of Belarusian artists’ influence abroad, with ongoing collaborations focusing on political and societal themes.

- Escalating Domestic Pressures: The challenges facing artists within Belarus are likely to persist or escalate, potentially resulting in more tragic incidents.

- Growing Community and Cultural Engagement: The trend towards fostering community engagement will likely gain momentum, building a more cohesive artistic community outside Belarus.

- Ethical Struggles within Domestic Art Institutions: Despite the seeming revitalization of the art scene, the complex ethical questions surrounding the avoidance of political content will continue to shape the cultural landscape of Belarus, with lasting impacts on how art engages with social challenges.