Like other areas of art, Belarusian photography is looking for support after 2020. The infrastructure is destroyed, the community is divided into those who stayed in Belarus and are forced to self-censor, and those who left and have more freedom, but struggle with the challenges of emigration. Photojournalists suffered first and foremost. In 2020, they were the voice of the people on the streets – with their help, the world learned about what was happening in the country. In 2025, Belarusian media are in a very precarious situation, there are almost no jobs for photojournalists. Most are looking for alternative sources of income, many are leaving the profession. For this reason, new projects are almost non-existent.

Photojournalism

Among the photojournalistic works, one can recall Paša Kryčko’s project “Map of Memories”, Alaksandr Vasiukovič’s coverage of the war in Ukraine, and two projects by Iryna Arachoŭskaja “Camera is temporarily unavailable” [“Камера часова не даступна”] and “To sleep peacefully” [“Спаць спакойна”] (in collaboration with Piotr Vujčyk). Paša Kryčko’s “Map of Memories” is a story about Belarusian emigrants experiencing a political crisis at a time when the problems of Belarusians are of much less interest to the world.

Iryna Arachoŭskaja also works on the topic of migration. In the series “Camera is temporarily unavailable”, the author observed the migration crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border through online cameras of the Belarusian customs authorities. In the second work, Iryna recorded the stories of Belarusian political migrants in Poland. The project “To sleep peacefully” was shown in the Duży Pokój space in Warsaw, at the Interfoto festival in Białystok, and at the Eugeniusz Geppert Open Plastic Workshop in Wrocław. Now Iryna is increasingly turning to the photo collage technique.

It is important to note the Belarusian winners of the largest and most prestigious press photography competition, World Press Photo. In 2021, Nadzieja Bužan won second place in the Breaking News category for her photo with Volha Sieviaryniec near the Akrescina prison, and in 2025, Taćciana Čypsanava, who was born in Belarus but now lives in New Zealand, won the Long-Term Project (Oceania and Asia Pacific region) category with a story about the Ngāi Tūhoe people. In total, these are the second and third victories in the entire history of the competition since 1955. The first winner in the modern history of Belarus was Taćciana Tkačova. In 2020, she took second place in the Portrait (series) category with a story about women who had abortions and the difficulties of society’s perception of this phenomenon.

Belarusians at the photo festival in Łódź

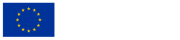

Since 2021, the most important platform for Belarusian photographers has been the Łódź Photo Festival. For three years in a row, Belarusian authors have had the opportunity to show their current projects at one of the largest photo festivals in the world. It is interesting to track how the themes of Belarusian exhibitions have changed. In 2021, photographers still lived in hope, and the theme sounded like a slogan – “Long live Belarus!” [“Хай жыве Беларусь!”]. In 2022, there is already a greater sense of confusion. The curators suggested that the authors reflect on the loss of home: actual – for those who left, and metaphorical – for those who remained in Belarus and do not have the opportunity to fully express themselves. In 2023, the crisis deepened. The name of this year’s Belarusian programme – Inbetweenland – is the suspension of society in a conditional limbo. The following year, there was no large Belarusian exhibition in Łódź. At the stands, you could see photo books by Belarusian authors and attend a panel discussion with figures from the field of Belarusian photography, dedicated to the current state of the photographic infrastructure, which has also changed significantly.

Belarus

The main annual photographic event for Belarusians was the Month of Photography in Minsk, the last edition of which took place in the fall of 2020 at the Korpus Cultural Centre. The focus on projects by Belarusian authors was steadily maintained by the Shklo platform and the Prafota project photography competition. Both initiatives ceased their activities after the political crisis of 2020. The Belarusian Public Association of Photographers was also transformed. Today, the association’s activities consist of organizing exhibitions and meetings of authors of past generations. Among them are exhibitions by Alaksandr Zazula, Alena Jeraševič, Anatol Drybas and others. A number of exhibitions are held in regional centres, with the participation of local authors. Portfolio reviews, lectures and meetings with photographers are held under the auspices of the association.

Photographic exhibitions can be seen at the National Centre for Contemporary Art (NCCA) in Minsk. Among the highlights is the exhibition “The Observer Effect” by the legend of Belarusian photography, Viktar Butra.

Infrastructure reconstruction abroad

The reconstruction of the Belarusian photographic infrastructure abroad began in 2023. The Fsh1 School of Photography, which was engaged in education and the creation of a community of photographers in Minsk, was transformed into the FSh1 Belarusian Photography Platform. The purpose of the platform was to create a community of Belarusian photographers, establish ties with international institutions, and amplify the voices of Belarusian authors. The organization began holding meetings in Warsaw and online, writing about Belarusian photographers, and released two podcasts – Dalahlad and Adnym kadram. In 2025, together with Polish colleagues Picture Doc FSh1 launched the free mentoring programme Do Art Together. In order to preserve the heritage, FSh1 plans to open a public library of Belarusian photo books in Warsaw in 2025. The collection of publications has already begun. At the moment, the collection includes more than 20 photo books and photozines. In March 2025, the future FSh1 library was presented at a photo festival in Rybnik, Poland.

In 2023, the Belarusian Independent Photographers Association (BIPA) began its work. The Association seeks to unite Belarusian photographers into a solidary community in order to be able to lobby the interests of authors at the regional and international levels. The organization operates in Vilnius and online.

The flagship project of BIPA is the PhotoArtDoc festival, which combines educational and exhibition programmes. Artist talks and lectures from Belarusian photographers are available on the association’s YouTube channel.

A separate focus in the Association’s work is the preservation of the heritage and information about authors of past generations.

Thanks to the PerspAKTIV project, a number of Belarusian photographers were able to visit residencies and get the opportunity to show their work in cultural organizations in Germany and Poland. The project promotes the integration of Belarusian artists into the European cultural space, and also creates safe conditions for creative realization through residencies. The authors finalize their stay in the residency with exhibitions or presentations, which expands the visibility of Belarusian photographers in the European field, as well as increases the network of professional contacts.

Projects

A large number of authors are building their own careers, trying to be represented in the European art space. In the project State of Denial [Стан адмаўлення], Saša Vialička explores the phenomenon of digital everyday life and how propaganda in the media tries to drown out any political news. The project was based on absurd detentions in the country – for praying, dancing or making a snowman. Some of the images in the project were made with the help of artificial intelligence, which took the headlines of Belarusian propaganda media as the basis for visualizations. In 2024, the project “State of Denial” was presented at the Circulation(s) European young photography festival in Paris, at the Zachęta National Art Gallery in Warsaw, and at the SIPF festival in Singapore. In 2025, it was nominated for the prestigious Images Vevey Book Award (will be shown at the Les Boutographies festival as the winner of the open round), and was also presented as part of a solo exhibition in Frankfurt.

The topic of the impact of propaganda on a person is also developed by Alaksiej Šłyk in the “GOO” project. In 2024, the work was presented at the Futures Hub in Amsterdam. Alaksiej visualizes the internal response to the flow of false, cruel and manipulative information from the official Belarusian and Russian media, which especially intensified after the 2020 protests in Belarus and the start of a full-scale war in Ukraine in 2022.

Lesia Pčołka in her project “Descent into the marsh” draws parallels between the protest movements of Belarus and Hong Kong. The author also draws attention to the problem of the development of modern technologies. In the hands of authoritarian systems, they have become a powerful tool of control and repression against dissenters. Another project by Lesia Pčołka “Roadside objects” will be shown at the Circulation(s) photo festival in Paris in March 2025.

It is noteworthy that Belarusian authors are particularly concerned with the themes of loss/feeling of home, memory and the search for support/roots, and national identity. In Alaksandr Kot-Zajcaŭ’s photo project “DOM.” [“HOME.”], through quiet and melancholic images, we encounter a conventional home, an inner feeling of this place. This is a long-term project that was implemented in the form of a photo book in 2019, and now, after being reworked, has gained new life at exhibitions in Poland.

In the project “At the Edge of Memory” [“На краю памяці”], Hanna Šot tells the complex stories of families from Western Belarus who suffered because of their Polish identity in the 1940s. After Stalin’s death and liberation from the camps, they had to make a decision – to stay in the Soviet country, risking repression again, or to build a new life elsewhere. The viewer is given the opportunity to make a personal choice and live with the consequences of this decision. The project is based on the memories of people whose relatives went through this path in real life.

Kaciaryna Kuźmičova, who herself faced emigration, is trying to redefine the concept of home. With the help of a camera, she captures images of a city of dreams and happiness. The project was called Hiraeth, which in Welsh means a mixture of boredom, nostalgia and thoughtfulness. Although the work is filled with peace, the images convey a hidden anxiety and uncertainty.

The inspiration for the creation of the project “The Art of (Not) Forgetting” by Volha Bubič was Yoko Ogawa’s book “The Memory Police”. During the Zoom calls, Volha asked the heroes and heroines to recall the most inspiring and most painful memories, and captured their emotions in a photo. “I want to feel the potential of memory as a space that belongs only to us — a space that we must especially fight for and especially protect in times of memory censorship”, Volha Bubič says about her work. The project was finalized in the form of a photo book, which is available in more than 20 libraries, art spaces and museum collections around the world.

In the project “My River” Maryja Elena Bane seeks an answer to the important question for many Belarusians “Who am I?”. On the one hand, she reflects on complex topics of identity, continuity, memory, repression, on the other – she gives hope, because “under uprooted trees, seeds always sprout.” The river in the project is a place of power that connects generations of the avatar’s relatives, as well as a metaphor for the spirit of freedom that is present in a person, no matter what. The project was shown in Belarus, France, Germany, Italy and Poland.

In the project “Rattus sapiens”, an artist Maryja Karniejenka fantasizes: what if humans are not the only intelligent species on earth, and a new civilization is already developing next to us? Her heroes are rats, who have always lived next to people and have been constant companions of man. Suddenly, tomorrow they will become the masters of the planet? In 2024-2025, the project was shown at three photo festivals in Poland: Święto Fotografii in Wrocław, Rise of Culture Festival in Rzeszów, and at the Rybnik Foto Festival in the form of a slideshow.

Belarusian authors have twice won the Noc Fotografii competition from Centrum Fotografii. Thanks to this, a slideshow of projects by Pavieł Savicki and Viktoryja Adamava was shown on the Market Square in the old centre of Warsaw.

Photobooks and photozines

In the period from 2021 to 2025, no less than 16 Belarusian photo books and zines were published. Among them are “The Square of Changes” [“Плошча Перамен”] by Jaŭhien Atciecki about the solidarity of residents of one of the Minsk courtyards in 2020; “Colours of Protest” – a series of four books with reportage photos about the Belarusian resistance in 2020, three of which are decorated with photos of red, black and white, respectively, and in the fourth, grey book, photographers tell stories about the photos that were not taken for one reason or another; “Descent into the Marsh – Belarus & Hong Kong” by Lesia Pčołka; “Relaxing Chamber” by Alaksiej Kazancaŭ; “Charomushki Odyssey” by Andrej Łohvinaŭ; “Long Way Home” [“Доўгая дарога дадому”] by the team of authors Maša Maroz, Hanna Karpienka, Ihar Babkoŭ and Valer Maroz; “Sorry for the Lack of Contact” by Kaciaryna Kuźmičova; “The Happy Society of Death” by Andrej Anro; “The Art of (Not) Forgetting” by Volha Bubič; “Betonium” zine by Kaciaryna Kuźmičova. A feature of Belarusian photo book publishing is the frequent use of two languages at once: Belarusian and English. However, there are publications only in Belarusian, Polish or English, and even with the use of the local Paliessie dialect – the book by Gola from Opole/Голя з Ополя “My Grandma – Director of the Morgue” [«Мое баба – діректор морга”].

Education

Interesting processes also took place in education. Some educational organizations and initiatives ceased operations after 2020. Due to the lack of opportunities, photographers in Belarus began to receive knowledge mainly from Russian photography schools, where there is the opportunity to study online, strong programmes and a staff of teachers, and the language of instruction – Russian – is well understood by Belarusians. There is no alternative to such training in Belarus. This affects the fact that Belarusian authors are increasingly immersed in the Russian cultural context. Photographers who find themselves in emigration have not yet settled down enough to be able to fully study. But in the future, it is these authors who will have more options for implementation thanks to direct contact with the European photographic infrastructure and closer contact with local institutions, field figures and the market.

Separately, it is worth noting the activity of Belarusian photographers in the field of social teaching. For example, through the New Home art and educational project, Julija Šabloŭskaja helps Ukrainian and Belarusian teenagers adapt to life in exile, and the duo of photographers Kanaplioŭ-Liejdzik conduct a course for Ukrainian teenagers and a course for Belarusian adults, “Družok”.

Conclusions

Belarusian photography is going through difficult times, but it has a tendency to recover in the current conditions. The authors are quite focused on the topics that were based on significant political events in our region (protests in Belarus, the war in Ukraine) and related problems – loss of home, forced emigration, preservation of memory, national identity and propaganda. Some of the activities have moved online. New photographic initiatives have begun to appear in places where there are many Belarusians – in Warsaw and Vilnius. Despite the trials, the voices of Belarusian photographers are still heard on European photographic platforms. Photo books by Belarusian authors also continue to be published. In Belarus, the public space is strongly focused on classic photography by the authors of past generations. Due to migration and reformatting of the infrastructure, another generation gap is looming. Young photographers get their information from alternative sources, most often Instagram and Pinterest, and are less inclined to project work.